Key Takeaways

- Central office staff, including superintendents, have filled in for classes.

- Support professionals have been asked to cover classes, leaving gaps in services.

- Educators call on districts for more safety measures to keep remaining staff healthy.

Schools across the U.S. rang in the new year with another COVID surge and another scramble to cover classrooms as the pandemic marches on. After the holiday break, fractures in the school personnel pipeline ruptured when the fast-moving Omicron variant infected huge numbers of educators or members of their families.

Erin Daly, a third grade teacher in Danbury, Connecticut, says approximately one third of the staff in her district is infected with the virus, is quarantining, or caring for family members who are sick.

In Connecticut and around the country, teachers are filling in for missing colleagues while district central office staff, even superintendents, cover classes, too.

“I jumped into gear and said, ‘I’ll clear my calendar and I’ll go over and teach a fourth grade class,'” Boston Public Schools superintendent told reporters.

In many cases, teacher's assistants are being asked to lead classrooms, often forced to leave their own students without all of the services they need.

Impact of Staff Shortages

What’s become clear is that existing shortages, exacerbated by the pandemic, have turned each school system into a precarious house of cards. To prevent them from toppling, educators agree that staff shortages must be addressed with higher pay, better working conditions, more safety measures, and greater flexibility for all staff.

Nationally, the ratio of hires to job openings in the education sector has reached new lows as the 2021-22 school year started and currently stands at 0.57 hires for every open position. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic was a key factor in one-third to one-half of teacher departures. As the pandemic persists, teachers are working more hours than ever. They are exhausted and demoralized, adjusting to changing models of teaching, often without appropriate training.

Even more educators are leaving the field, and many are leaving mid-year. The worst case scenario is becoming reality. There is literally not enough staff to keep schools open." - NEA President Becky Pringle

The Biden Administration announced plans to distribute 10 million free COVID tests to schools every month in an effort to keep them open, a move applauded by educators.

Daly says most educators want to be with their students in person, albeit with all of the layered COVID safety measures in place (including the provision of promised N95 masks yet to be delivered to her district), but the staff shortages have made that nearly impossible.

When one card in the house falls, the rest can easily follow. Last week the Danbury school district shut down for three days because of a one-two punch of a powerful snowstorm and insufficient staff to fill classrooms. There was no remote option, so instruction was cancelled.

With staffing this close to the bone, there must be flexibility for remote learning, Daly says. It doesn’t work having a rigid policy that requires in person learning with no backup for remote learning when necessary. When schools are forced to close, students can’t learn.

“We want them to have a day that counts,” Daly says. “Our district and all Connecticut districts should have the flexibility to move to remote instruction for short periods of time without requiring it to be made up.”

Breaking Point

A survey conducted this week by Connecticut’s Board of Education (BOE) Union Coalition found that, while educators and staff agree that in-person learning is best for students, the vast majority of respondents, 88 percent, believe superintendents should have the flexibility to move to remote instruction for a short period of time, without having to make up the days, to ensure safety in the classroom.

The survey also found that more than half (55%) of paraprofessionals said they have been unable to fully implement their assigned students’ IEP and 504 plans due to staff shortages.

Education support professionals (ESPs) are definitely feeling the impact of shortages all over the country. Bus drivers are out, snarling routes and increasing ride times. Cafeteria staff are in short supply, limiting food options or adding responsibilities to already enormous workloads of those who can come in.

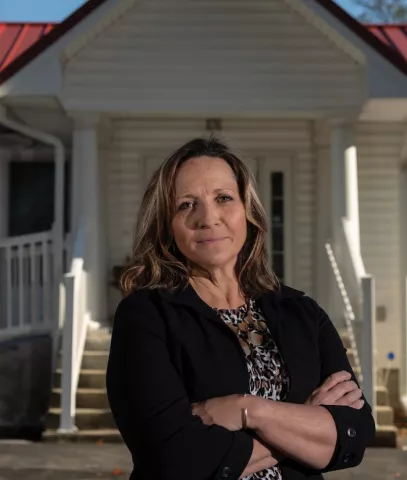

In Calvert County, Maryland, Stacy Tayman, a human resources associate and president of the Calvert Association of Educational Support Staff (CAESS), says paraprofessionals (called Instructional Assistants, or IAs, in her district) are at the breaking point.

“They are being deployed to cover classrooms and then there’s a gap in service,” Tayman says. “IAs are hired for a purpose – whether it be to provide interventions for students or pre-K support, but when they’re called away from those assignments their students aren’t receiving everything they need.”

The union negotiated increases in pay by an additional $14 an hour for IA’s who are pulled into classroom coverage for 90 minutes or more a day. The hike in pay for the increased work has been rewarding for some but not for others. While all ESPs need, and deserve, more pay, offering a temporary hike in pay for an emergency situation is a bandaid that doesn't address the underlying issue – the need to pay support staff higher salaries to perform their actual jobs.

“I’ve heard many IAs say they don’t even care about the pay increase, they just want to go back to their regular jobs because they’re burned out by being pulled in so many directions,” Tayman says.

Focus on Entire School Community

School nurses are also hitting their limits. They’ve been working long days since the beginning of the school year performing contact tracing, holding vaccine clinics, and helping with testing, all of it done with little or no clerical assistance for the mountains of paperwork caused by additional pandemic duties, that is until the union successfully advocated for some support.

But it is time to finally find lasting solutions to staff shortages worsened by the COVID crisis, Tayman says. That starts with better pay.

“Our support staff is getting pummeled during the school day and then they have to go to a part time job just so they can pay the bills,” she says. “It depletes their physical and emotional reservoirs. It’s really hard to be able to manage all of that and then be able to really show up and be your best for students.”

Much of the news these past few weeks has centered on teaching shortages, but it’s actually a crisis of school personnel all across job categories, and solutions must be focused on everyone who works in the school community, Tayman says.

“Until we realize the impact that the support staff has in bolstering the entire system, and until we put the necessary investments into the structure that holds all of the pieces together, it’ll keep falling apart,” she says.

In the near term, Tayman and Daly in Connecticut continue to advocate for more safety precautions to protect the staff that is still healthy and working.

On January 12 in Connecticut, teachers, ESPs and other school personnel held a “blackout” to raise awareness about more safety measures needed in schools. The Connecticut Education Association (CEA) joined together with other Board of Education employee unions representing educators, paras, custodians, nurses, cafeteria workers, bus drivers, monitors, and other support staff to amplify the call for safe learning and teaching environments in schools.

“Being the doers, the people on the ground who get the job done, we’ve created a list of things that would make a difference and keep our schools safe and secure,” CEA President Kate Dias said during a news conference.

Educators are advocating for nine specific measures: more aggressive testing protocols and assessment of symptoms to closely monitor students and teachers before they enter schools; access to COVID-19 vaccination and free testing at all schools, including weekly pool testing; N95 masks and in-home test kits for students and staff, as well as a requirement that N95 masks be worn by all in school buildings, regardless of vaccination status; continued social distancing and improved ventilation; a prohibition on large group gatherings, combined classes, and dual teaching; and a prohibition on requirements that staff use sick time for quarantines.

At Daly’s school in Danbury, every staff member proudly showed up in black to stand up for themselves and each other. Their hope is that state administrators and lawmakers will take notice.

“We have been going above and beyond, especially during this pandemic, and we have earned this support,” Daly says. “We are exhausted.”

Solutions: Ensuring Every Student Has Caring, Qualified & Committed Educators