Key Takeaways

- In many places, a lack of affordable housing is exacerbating the shortage of teachers, bus drivers, classroom aides, and other education support professionals.

- NEA-affiliated unions are tackling the issue in a variety of ways. Demanding more pay is the simplest. Other strategies include the development of teacher or employee housing.

How do you buy a $650,000 house when you get paid $40,000 a year? Santa Fe’s new teachers have no idea.

The median home price in their community has increased by more than $240,000 over the past five years, according to Realtor data. That cute 2-bedroom adobo house near the city’s arts district? It’s $990K.

And it doesn’t have central air.

When teacher Jamie Torres moved back to Santa Fe in 2018, after a stint in the Peace Corps in Africa, she was lucky to have family nearby. “I looked everywhere, hoping to find a hole in the wall to rent, but I couldn’t,” she recalls. “I was couch surfing at my sister’s, then my grandparents’ and my parents’.”

Today, she still considers herself fortunate. “I have a little standalone casita that my landlord bought for his daughter and I’m always like, ‘I hope your daughter likes New York!’” she laughs. Because Torres was willing to fix the holes in the walls and remediate the smell of urine that previous tenants left, her landlord gave her a “break” on the monthly rent. It’s $1,800 a month.

The rent is more than half her income, but at least she gets to live in the community she serves. Many of her colleagues—young and old—live 45 minutes away. It’s a challenge to attend school events, like the high school musical. And, if they want to speak to school board members about policies affecting their classrooms, like class sizes or curriculum, they need to commit to another 90-minute drive at night.

Often, they opt to leave Santa Fe to work where they live, says Grace Mayer, president of NEA-Santa Fe. In a recent survey, half of Santa Fe teachers said they may not return next year because of housing prices. “This is completely about recruitment and retention,” she says. “People are excited to work in Santa Fe and then they call us and say, ‘I think I’m going to have to move back home!’”

No Housing, No Staff

Across the U.S., a lack of affordable housing is exacerbating the national shortage of teachers, school bus drivers, paraprofessionals and other education support professionals.

In rural communities, the problem stems from a scarcity of rental units. In urban areas, like California’s Bay Area or Silicon Valley, there’s availability—for tech millionaires or hedge-fund managers. Not so much for educators.

If teachers got paid what other professionals with the same level of education and experience earn, then educators could afford to live among the accountants and engineers. Instead, they earn about 20 percent less than similar workers.

Meanwhile, in tourist destinations like Santa Fe, New Orleans, or Colorado’s ski towns, landlords can turn a much larger profit through short-term rentals on online marketplaces like Airbnb.

Do the math: Torres pays $1,800 a month, while similar Santa Fe homes rent on Airbnb for $225 a night—or $1,600 a week.

The bottom line is this: where affordable housing is in short supply, so are educators. In San José, Calif., where the median house price is $1.2 million, the superintendent was needed to sub for a P.E. teacher this fall. In Aspen, Colo., where the median house price is $5.4 million, the superintendent was driving a school bus.

Like many issues, the Covid-19 pandemic worsened the shortage of educators in these communities, but the problem of affordable housing for educators has been around for years. Torres, for example, was couch surfing in 2018.

Just Pay Them More!

There are two ways to help teachers and other school employees—bus drivers, paraeducators, custodians, etc.—afford to live in the communities they serve.

The first is simply this: Pay them more. If teachers got paid what other professionals with the same level of education and experience earn, then educators could afford to live among the accountants and engineers. Instead, they earn about 20 percent less than similar workers.

The second strategy is through what the Economic Policy Institute calls “housing-related interventions,” such as district-owned housing or low-interest mortgage rates for educators.

In Palo Alto, Calif., teachers will soon have access to a new 110-unit apartment building, spearheaded by the local Board of Supervisors, says Palo Alto Education Association President Teri Baldwin.

“We’ve been advocating for a long time for affordable housing for educators,” says Baldwin. “We’ve got people living all over the Bay Area. They’d love to go evening events and be present in their schools, but it’s hard to be involved in that way when you have a 2-hour drive!”

Similar “teacherages” have been built in Santa Clara, Calif.., and Nags Head, a beach community in North Carolina. “It’s not just a recruitment tool, it’s a retention tool,” Elisabeth Silverthorne, of the Dare County Educational Foundation, told Education Week in 2018.

Santa Fe’s Solutions

In Santa Fe, union members have been working on both things: more pay and less expensive housing.

In March, after an energetic lobbying campaign by NEA-New Mexico, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed into law $10,000 teacher pay raises. Minimum pay will go from $40,000 to $50,000 for new teachers, and from $60,000 to $70,000 for the most experienced teachers. All New Mexico school employees will see at least a 7 percent raise.

Better pay will directly address the cost of living, which includes more than housing, Mayer points out. Health care costs are constantly on the rise, and “childcare is $900-$1,200 a month,” she says. “If you have a young family, you just can’t live here. You can’t make it work,” says Mayer.

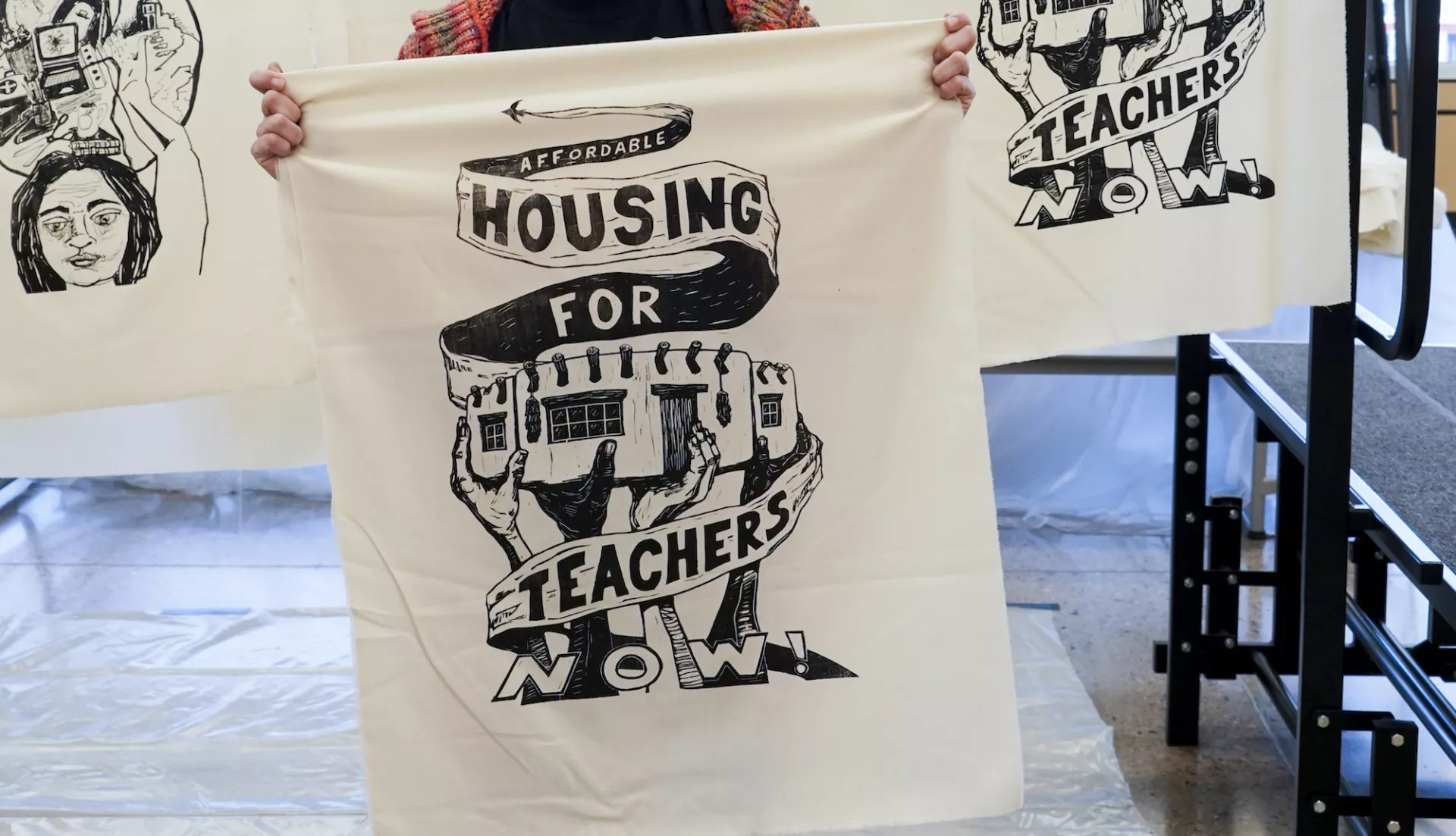

Meanwhile, union members also are working to make housing more affordable. For the past year, a NEA-Santa Fe committee, led by Torres, has helped teachers to share their stories and shine a spotlight on the issue. In November, thanks to their efforts, the Santa Fe school board passed an emergency resolution, creating a task force to address the educator housing crisis.

Last month, an anonymous person donated $400,000 to a local nonprofit to provide the down payments for 10 or more teachers.

Meanwhile, union members also are working with school board members to lobby for federal funds to turn unused school district buildings into teacher housing. “It looks like this is going to happen—maybe 20-25 units,” says Torres. “It’s the tip of the iceberg, but it’s good that people are acknowledging the issue.”

For Torres, it’s never just been about the commute.

“My thing was, if I’m going to teach in Santa Fe, I want to be able to vote in Santa Fe. I want a say on bonds, and I want a say about the people, the elected representatives, who are making decisions in schools,” says Torres. "I want a voice."