A wave of laws limiting the freedom to vote is sweeping across the nation. And voting rights advocates are sounding the alarm. Is this “Jim Crow 2.0”?

On the surface, these new restrictions—such as fewer early-voting locations, reduced voting hours, and limits on voting by mail—may sound innocuous. But they are actually carefully targeted to diminish the voting power of People of Color.

To understand the real-world impact of these limits on voting, it’s worthwhile to look back at life under Jim Crow laws, which prevented Black southerners from exercising their lawful right to vote for nearly a century. What’s happening today looks eerily familiar.

Mississippi in the 1950s

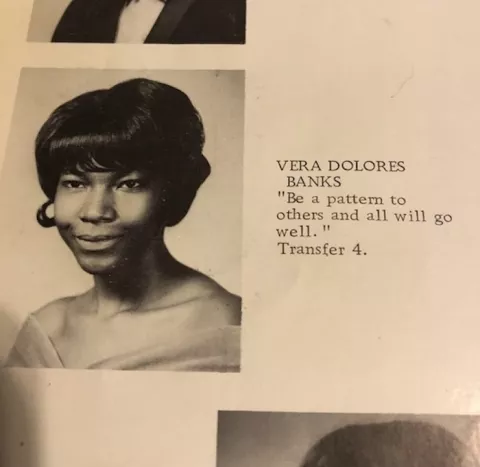

Retired social studies teacher Vera Watson was born in Clinton, Miss., in 1950. She grew up in height of the civil rights era, where the struggle for justice and equality for African Americans wasn’t a page from a history book—she lived it! “[My parents] were denied the right to vote— they couldn’t even register,” Watson says.

"They were told "You just can't" or barred from entering a White part of town to vote.

A bigger, more punitive message was implied: “If you do register and vote, you will have no job,” Watson says.

These stories coupled with her own experience as one of the first Black students at Forest Hill High School, in 1968, deepened Watson’s commitment to civic engagement.

She recalls that year: “Nobody wanted us there, and I was treated unkindly.”

On the school bus, some students threw paper at her, while others called her names. Teachers talked about Black people in openly racist and disdainful ways. No one spoke to her, and she sat alone at lunch. People made threatening phone calls to Watson’s parents, demanding they withdraw her from school.

And school officials ignored her and her family’s grievances.

“Ever since high school, I’ve been involved with organizations that advocate for the rights of others. I was closed-mouthed back then, but not anymore,” she says.

Her activism has centered on voting rights, working with groups such as the Federation of Colored Women and the League of Women Voters. Today, she works closely with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People—Clinton Branch on voter education and registration.

“We need to be heard, and the only way that is going to happen is if we’re informed and involved,” she says.

Access Denied

“From the beginning, those in positions of power have only wanted certain people to access the vote,” says Jesse Evans, a high school American government and civics teachers, in Athens, Ga.

It’s intentional and goes as far back as 1776, when the nation’s founding fathers limited the vote to mainly White men, who were over the age of 21 and owned land—a group that made up only 10 to 20 percent of the population.

It would take 80 years before all White men were granted the right to vote. Another 80 years would go by before Black men could vote, and 50 years until this right was extended to women.

Still, many elected officials found loopholes. Beginning in the late 19th century, political operatives in Southern states employed voter suppression tactics, known as Jim Crow laws, which imposed literacy tests, poll taxes, voter roll purges, and grandfather clauses that said you could vote only if your grandfather had voted.

These discriminatory laws kept Black people from the polls until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 finally made them illegal. But protecting voting access has been a contentious struggle ever since.

Beyond Jim Crow

In 1970, after Charles Gonzales was president of Student NEA (today called Aspiring Educators), where he was a prominent leader in the movement to lower the voting age to 18. He went on to work for the Youth Citizenship Fund, an organization born out of NEA, to get young people ages 18 – 25 to register to vote.

A skilled organizer, Gonzales partnered with activists from the Voter Education Project (VEP) to help Black people in the Mississippi Delta register to vote.

He also worked on voter mobilization tours led by civil rights icons John Lewis—director of VEP at the time and a future congressman—and then- Georgia State Rep. Julian Bond. They traveled to churches and civic organizations throughout the South, encouraging Black people and Mexican Americans to register to vote.

“Their speaking tours … not only gave hope to people … but gave them the courage … to put their life on the line to register to vote,” says Gonzales, who is now an NEA-Retired member.

“We continue to have a lot of injustice in our society. We can and should be doing better by people who are in disadvantaged positions, racially and economically.” - Jesse Evans, educator

Gonzales’ experience working on political campaigns gave him an unobstructed view of the consequences of voter suppression tactics, such as limiting voting hours and registration locations in African American and Hispanic neighborhoods.

Black and brown men who worked the farms were prohibited from taking the day off from work to register to vote. Many held multiple jobs and were left with little time for much else. Child care was often unavailable and prevented parents from heading to registration sites, often miles away from their homes.

But it was only in the Mississippi Delta that Gonzalez witnessed the mortal danger facing Black people if they dared to go to the polls.Even after Jim Crow laws were abolished, some African Americans were intimidated, beaten, and even killed by White men when they tried to vote.

“[Black people] feared being identified by racist White people after writing their names on voter registration papers,” Gonzales recalls. “Our policy was to get off the road before sunset. We would often hear gunshots nearby. It was dangerous.”

Understand the Barriers

Many barriers from the Jim Crow days have remained in place.

One explanation is somewhat straightforward, says David Jesuit, a political science professor at Central Michigan University, and it has to do with the resources that are available to people. “Political science for decades has had this finding … that the more affluent and welleducated you are, the more likely you are to participate, because the barrier is lower,” he says.

It’s called the socio-economic resource bias and means that when people have benefits, such as paid time off from work, sustainable transportation, and access to child care, it’s easier to get to the polls. Meanwhile, the opposite holds true for many, particularly for People of Color in lower-income areas, which keeps voter turnout low.

Restricting access to the vote doesn’t only have a random effect on a group of people, Jesuit says. “It affects public policy outcomes, too.”

Those policies include whether public education gets adequately funded or continues to be shortchanged, or whether it’s easier for citizens to exercise the right to vote.

Georgia, a Case of Access and Suppression

Voter suppression efforts are back with vengeance today, and Evans is seeing this firsthand in his home state of Georgia.

He is involved with a local non-profit that works to increase civic engagement through voter registration and get-out-the-vote efforts. He also served a four-year term as a non-partisan member of his local board of elections from 2017 – 2021.

“People often don’t realize how important local boards of elections are,” he says.

His work on the board during the 2018 and 2020 elections helped expand voting locations and early-voting sites—including one in a predominately Black and brown, lower-income community that was designated an early-voting location for the first time ever.

Additionally, they extended voting hours, expanded absentee voting, and installed more 24-hour ballot drop boxes for the 2020 election.

“It was a record turnout for early voting and absentee voting,” Evans says.

That year, Georgia made international headlines as high turnout among African American voters in the state helped decide the U.S. presidential race and the balance of power in the U.S. Congress. It’s no coincidence that in the wake of that election, many of the state’s legislators are trying to once again to limit Black people’s access to the vote.

In March, Georgia enacted a new, more restrictive voting law. Among other changes, voters will now have access to fewer drop boxes; they will no longer receive absentee ballots in the mail unless they request them, which impacts many Black voters who tend to vote by mail; and mobile voting centers will no longer be available, unless there is a state of emergency.

In state legislatures across the country, politicians have introduced more than 500 similar state bills, at least 30 of which have become law. These measures suppress the voices of many voters—particularly Black, brown, and Indigenous voters, senior citizens, students, and those with disabilities—and are a threat to U.S. democracy.

Says Evans: “Some people think that rather than embracing democracy, prioritizing the voice of the people, and maximizing the franchise to include as many eligible voters as possible, [they’re] comfortable trying to win elections by deciding who can vote and can’t vote in an election.”