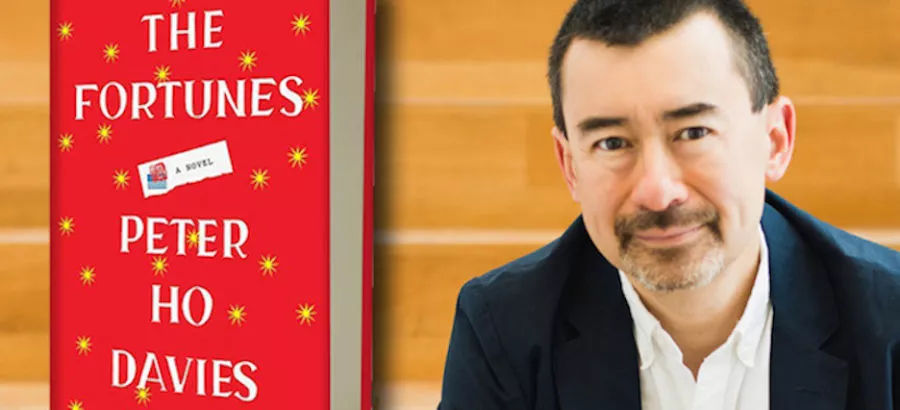

Economics, identity, racism and immigration are hotly debated topics in the 2016 presidential race, but they’re also themes of Peter Ho Davies’ latest book The Fortunes, an historical novel rife with discussion points sure to enrich any high school classroom. NEA Today recently talked to Davies about his work and the relevance of its themes for students.

How is The Fortunes relevant to what many middle and high school students cope with in terms of developing their identities?

Peter Ho Davies: All our identities – young or old – are a kind of negotiation between an inner self (the way we see ourselves), and an outer self (how we’re seen, and how we project ourselves to others). That sense of identity has been a subject of my work for years – my last novel The Welsh Girl considers what it means to be Welsh (as well as English, German, Jewish), and The Fortunes explores the question in regard to Chinese Americans. As someone who grew up in a mixed race family, conscious of my half-ness (half Welsh, on my father’s side, half Chinese on my mothers), I’m very sensitive to the way that many of us - Chinese Americans, but also other so called “hyphenated” Americans – can feel divided. Such dual identities can sometimes imply a choice – are we more one thing or the other, but that choice can feel like a test, a loyalty test, even a purity test. If we stay close to the heritage of parents or grandparents are we failing to fully engage a wider culture? If we assimilate and engage that culture are we abandoning or betraying our heritage? Thought of as a choice, it’s lose-lose. Either choice makes us feel less authentic somehow. But I’d like to suggest we can reject the binary choice and see hyphenated identity as a third option. My book, in a way, is not so much about Chineseness or Americanness, as about the hyphen.

But while the dilemma I’m describing is especially acute for “hyphenated” Americans, I’d argue that the struggle to reconcile our identities is universal – especially acute in our teens, but on-going. After all, we are many “selves” – the self with our family, the self with friends, the self with colleagues. Even the familial self is divided – the self I am with my own parents isn’t the self I am with my child. And let’s not get started on all those new selves – the ones we project via social media! We struggle sometimes to reconcile these selves out of a sense that one must be the true self, the real me, and we feel guilty or awkward or hypocritical especially in spaces where these selves overlap (a teenager brings a friend home to meet the parents, say). But maybe all those selves are true facets of who we are…Adolescence seems a period of identity change, of identity confusion, often laced with shame. The idea that we can all be, and all are, more than one thing, that we’re not defined by a single identity, feels freeing to me. We’re all subject to stereotyping after all – girls and boys, as well as racial minorities – which are the ultimate imposition of a narrow self by the outside upon us.

Why do you think Chinese American history isn’t a bigger part of the curriculum and why should educators give it more prominence?

PD: There is a lot of important material vying for a place in the curriculum, but maybe one way to approach Chinese American history is not to think of it as it’s own topic area so much as a part of our larger American history. The building of the Transcontinental feels emblematic in that regard. It’s a project that binds the country together after the Civil War, and opens up the West. It’s a literal manifestation of nation building in that sense…and it’s built by immigrants -- Chinese from the West, Irish from the East. I go further in the book and suggest that the discrimination against the Chinese in California post-completion of the railroad is also a darker aspect of nation building. Ironically, the railroad allowed labor to flood west and created fierce competition for jobs between whites and Chinese immigrants there. White immigrants from extremely varied backgrounds – German, French, English, Irish – are in some sense “united” by and against the presence of an “other."

How can literature help students make sense of racial intolerance? How does your book address those issues?

Peter Ho Davies Webinar

Register to hear and speak to Peter Ho Davies, presenting his book The Fortunes on October 6, 7-8 PM EDT. Download usable instructional activities and enter a drawing to win a classroom set of The Fortunes which might be the perfect book for high school teachers that reimagines the multigenerational novel through the fractures of an immigrant family experience. Register here.

PD: In the case of The Fortunes I’m interested in the historical forces that shape Chinese American identity – including the formation of stereotypes and how we might question them. The “model minority” stereotype could be seen to apply to Ah Ling, say. He’s such a good worker he changes one stereotype – the Chinese are physically weak – but in doing so helps form another (they’re hard-working, loyal employees). I find myself constantly drawn to the historical ironies of racism. The Chinese are discriminated against until WWII when they become allies in the war against Japan (and the Japanese become subjects of racism). Vincent Chin’s mother experiences Japanese aggression in China, comes to the US to escape it, and yet her son is killed 40 years later when two Detroit autoworkers mistake him for a Japanese, in a period when Japanese competition in the car sector seems to be imperiling American jobs. After his murder, Vincent’s mother makes common cause with Japanese Americans to get justice for her son. What that suggests to me is an arbitrariness to racial intolerance, the way it shifts often in relation to the historical moment (today, say, China is the subject of our angry economic anxiety rather than Japan). What that says is that racial intolerance isn’t some fundamental difference between peoples (“those people are just that way”), but rather mutable, situational – which also offers us hope it can be changed.

When people discuss racism in America, the focus is mostly on the experiences of African American or Hispanic populations. Why not Asian Americans? How do Asian Americans experience racial stereotypes and racism that’s similar to and different from other marginalized groups of people?

PD: The common argument is that the stereotypes of Asian Americans are positive ones…Asians are hard-working, high achieving, good at math and violin, the “model minority” etc. But those stereotypes, even if positive, connote burdens. What does it mean to be an Asian who’s not good at math, but wants to be an athlete, say? Even a positive stereotype can be limiting in that regard. On the other hand what does it mean to be Asian and to in fact be good at math? Does confirming one aspect of the stereotype implicitly support other modes of stereotypical thinking? Asian stereotypes, after all, aren’t all positive (the stereotype of Asian men having small penises say is one I refer to in The Fortunes in a high school context).

Why is it important that books about Asian experiences be included on student reading lists, not only for Asian American students, but for all students?

PD: Because the experiences of one group never happen in isolation, but always in context. Asian American experiences can shed light on the experiences of other groups (and vice versa, of course). A mission of much fiction is the desire for experiences beyond our own – that’s true of escapist fiction (what’s it like to be a spy, or an astronaut?) but also I’d argue it’s a pleasure of most reading. There’s a natural, innate human curiosity about others, which underlies a desire to understand and communicate. Fiction is a space for us to practice the kind of empathic connection that we can also enjoy in life.

How can books like yours help students understand – and perhaps become more empathetic about -- events like the current immigration policy debate and the migrant crisis?

PD: Ideally, such books invite readers to stand in the shoes of the immigrants, but in the case of The Fortunes I hope reader will also come to take a longer, broader view of the issue in a historical context. It’s valuable, and maybe even hopeful, to see that the nation has grappled with such challenges in the past and been able to work through them, albeit painfully in some cases.

How are your experiences as a young person, and as a student, reflected in your writing?

PD: Some sense of isolation and loneliness as a child – some sense of otherness – likely made me a writer, but a lot of life experiences have shaped the writer I’ve become. I loved science fiction as a teen – it’s what I first wanted to write (inspired by making-of documentaries about Star Wars and Star Trek!) – and indeed I majored in Physics in college. But around 18 when my grandmother developed dementia and had to be institutionalized I began to write about materials closer to home and more emotionally challenging which suggested new potentials in my fiction to me. That story, my first published, changed the course of my life. And yet, my study of physics still informs my writing. The idea of wave-particle duality – the mind-expanding notion that one thing (matter, or light) can be understood via two mutually exclusive concepts – shapes the way I think about character, about people, who are never one thing or another, wholly good or wholly bad, but always a mixture of both.