Mundelein High School in Mundelein, Illinois

Mundelein High School in Mundelein, Illinois

Educators are chock full of good ideas, especially when it comes to the betterment of their students. So when Illinois Education Association (IEA) member and board director Andrew “Andy” Hirshman, a social studies teacher at Mundelein High School, invited teachers, school staff, university researchers, and parents to an event in February 2017 to brainstorm ideas about how to improve several neighboring schools within different districts, it didn’t take long for those good ideas to turn into action.

Discussions that day centered on increasing parental and community involvement, eliminating school inequities by creating a path for advancement for every student. At the end of the meeting, the Illinois Opportunity Coalition—with support from a $48,000 NEA grant—was born. The coalition, which includes several IEA members, addresses opportunity gaps (traditionally referred to as achievement gaps). The group’s efforts have had an immediate impact on thousands of students, as well as educators, school staff, and community members.

"The Opportunity Coalition is really an outgrowth of what we have been doing at the IEA for many years now,” says Hirshman. “Finding willing partners to collaborate with in order to help improve education is just what we do."

Since its inception, the coalition has accomplished much. Here’s a quick look:

Removing Barriers to Parental Involvement

Despite the high percentage (45) of Hispanic students at Mundelein High School, located in a northern suburb of Chicago, parental involvement was low. To reverse this trend, Hirshman and other coalition members reached out to people they knew could help. Sol Cabachuela was one such person.

Cabachuela has a long history of community volunteerism. She is, for example, the president for the Mundelein Latino Police Academy and a mentor for Kids Hope organization at one of the local middle schools. She was also recently appointed as Mundelein’s new Acting Village Clerk. But her role as a member and community liaison for the Mundelein High School Parent Ambassadors program is what makes her a shining star within the education community.

“I don’t have kids in the high school yet,” says the mother of seventh and second grade students, “but I wanted to get involved because I understand the culture, how it works, and how to respond.”

Her work with the ambassador’s program, which helps connect parents, feeder schools, and community members with educators and students from Mundelein High School, has created several opportunities for parental involvement. So when Cabachuela was tapped to help the coalition, she jumped at the chance.

“Many parents didn’t know what’s going on, and it wasn’t from a lack of interest,” she explains. “Most parents work two jobs. Others didn’t have access to email, let alone an email account. When I started to engage with families I saw they were missing basic tools that prevented them from being a part of the school community,” she says.

Cabachuela used her networking skills to reach out to families using tried and true techniques, such as making one-on-one connections. “They like to see someone from the community whom they know,” says Cabachuela, adding that “it’s all about trust.”

A pivotal and proud moment for the coalition and the parent ambassadors came when the group drew a large crowd to a back to school event this past year. After several conversations with Hispanic families, they learned that many would skip the back-to-school cookout, traditionally hosted for the football team, because “they like soccer,” explains Andy Hirshman. To create a more welcoming environment, they held a season opener cookout for the football and soccer teams that drew nearly a thousand people.

Since then, with Cabacheula at the helm, other parents have volunteered to connect with the families of incoming freshman or host lunches or dinners at their homes or at the high school. “This work is about finding opportunities for families,” says Cabachuela, “and making sure families know they have a support system in place.”

With parental involvement on the rise, educators and school staff can turn their attention toward other matters that are equally important, like equity.

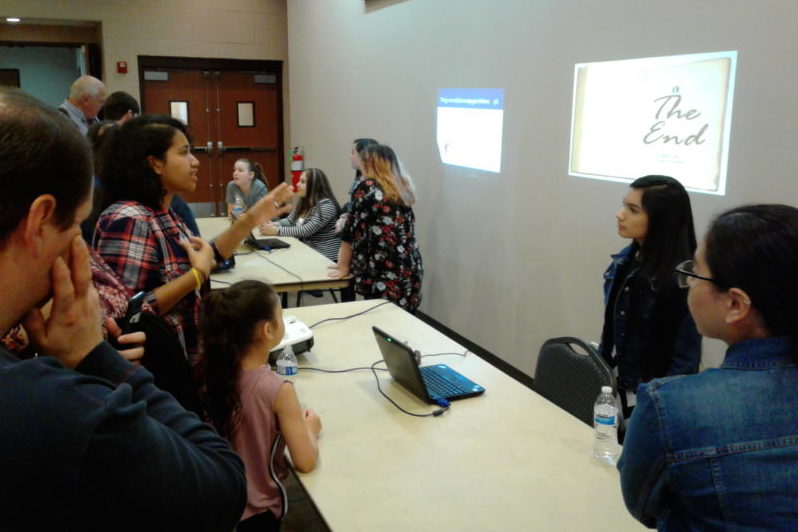

In May, the Round Lake Opportunity Coalition showcased student led research projects that were a culmination of a year long collaborative process between Opportunity Coalition members, which includes members of the Illinois Education Association, district leaders, and local community leaders.

In May, the Round Lake Opportunity Coalition showcased student led research projects that were a culmination of a year long collaborative process between Opportunity Coalition members, which includes members of the Illinois Education Association, district leaders, and local community leaders.

Closing Gaps in Honors Classes

Many students of color nationwide are still underrepresented in honors and advanced placement (AP) courses. Some placement processes assign students to different classes based on prior achievement. This is known as tracking. Mundelein High School uses a similar system—that is until school staff learned that many students of color whom by all of their indicators (test scores, grades, attendance) should have been taking rigorous courses were not.

After more than a year of research, parent outreach, focus groups, and collaboration among teachers, support staff, administrators, and the local union, an Earned Honors model was piloted in Mundelein’s World Studies classes during the 2017-2018 school year.

Under this model, no one is slotted for “honors” or “regular” classes. All students are kept together, which better reflects school demographics. The earned honors distinction is based on the work students produce and for those who struggle additional academic support and scaffolding are provided.

The efforts from members of the Illinois Education Association through the Opportunity Coalition fit within the requirements of the Every Student Succeeds Act, which gives parents, teachers, and community members a seat at the decision-making table. If your school needs to improve in certain areas, turn to NEA's My School, My Voice for guidance and connect with your state association.

“You can say ‘they have access,’ but for this to be true, the right supports need to be in place for students to actually access the curriculum,” says Stacey Gorman, director of curriculum and instruction for the high school and a member of the Illinois Opportunity Coalition. “It wasn’t just the world studies teachers. There were interventionists and instructional assistants who supported kids and worked with teachers to make sure this model was successful.”

Success came quickly, too. Data revealed that there was an increase of 28 percent in the number of Hispanic students earning honors compared to the previous “ability” tracking model. Forty-five percent of students who earned honors, but were not enrolled in any other traditional honors course, were Hispanic students.

Next year, school staff has decided to do away with AP World History, and instead, every freshman will be in earned honors World Studies.

Mundelein isn’t the only benefactor of the coalition’s work. Gains have been made in other areas, too, such as in neighboring Round Lake, where educators worked with teams of students who engaged in action-based research that addressed different community issues.

Connecting Students to Communities

The following may sound familiar: students with good grades, perfect attendance, and (for whatever reason) unengaged in school and community activities. These were some of the characteristics that Matthew Howe, a Human Geography teacher from Round Lake High School and a member of Education Association of Round Lake, and three other educators from the school district were discussing back in February 2017 when the Illinois Opportunity Coalition hosted its first meeting.

The question was asked: “what can we do?”

Howe and other educators organized and formed a district-level group called the Round Lake Opportunity Coalition and tapped nearly 90 students from Indian Hill Elementary (4th graders), John T. McGee Middle School (7th graders), and Round Lake High School (10th graders) to take on issues that impacted their community.

Students formed mixed-grade groups based on topics, which ranged from stopping gun violence and reducing bullying to improving local water quality and the need to plant more trees. They met five times during the course of a year to work on their projects, even meeting with community members, such as firefighters, members from the city planning council, and school counselors.

The culmination of their work resulted in the first annual Round Lake Opportunity Coalition Showcase, an open house style event where on May 18 student presented their findings to a room-full of parents, community members, and educators.

“The outreach aspect was really important and seeing students start to understand that they are part of this community, too,” Howe says, “but the collaborative part of the project was big, too.”

Teachers who worked with students had coverage from substitute teachers, students had the resources they needed to complete the work, and when community members were called to help, they showed up. “We were all working together,” Howe says, “and it was really cool to see students, the union, the administration, the community make this project successful.”

The Illinois Opportunity Coalition has created excitement among educators and their allies. What initially started out in three school districts has spread to eight different communities, with a reach of 50,000 students.