Key Takeaways

- Of the official 600,000 Cherokee Nation citizens, fewer than 2,000 speak Cherokee—and most of them are aging.

- When Native students learn Native language and culture, they're more likely to go to school. Their mental health is significantly better.

- There are a lot of challenges to providing these classes. Chief among them? Finding teachers.

In 100 Years, Will Anyone Speak Cherokee?

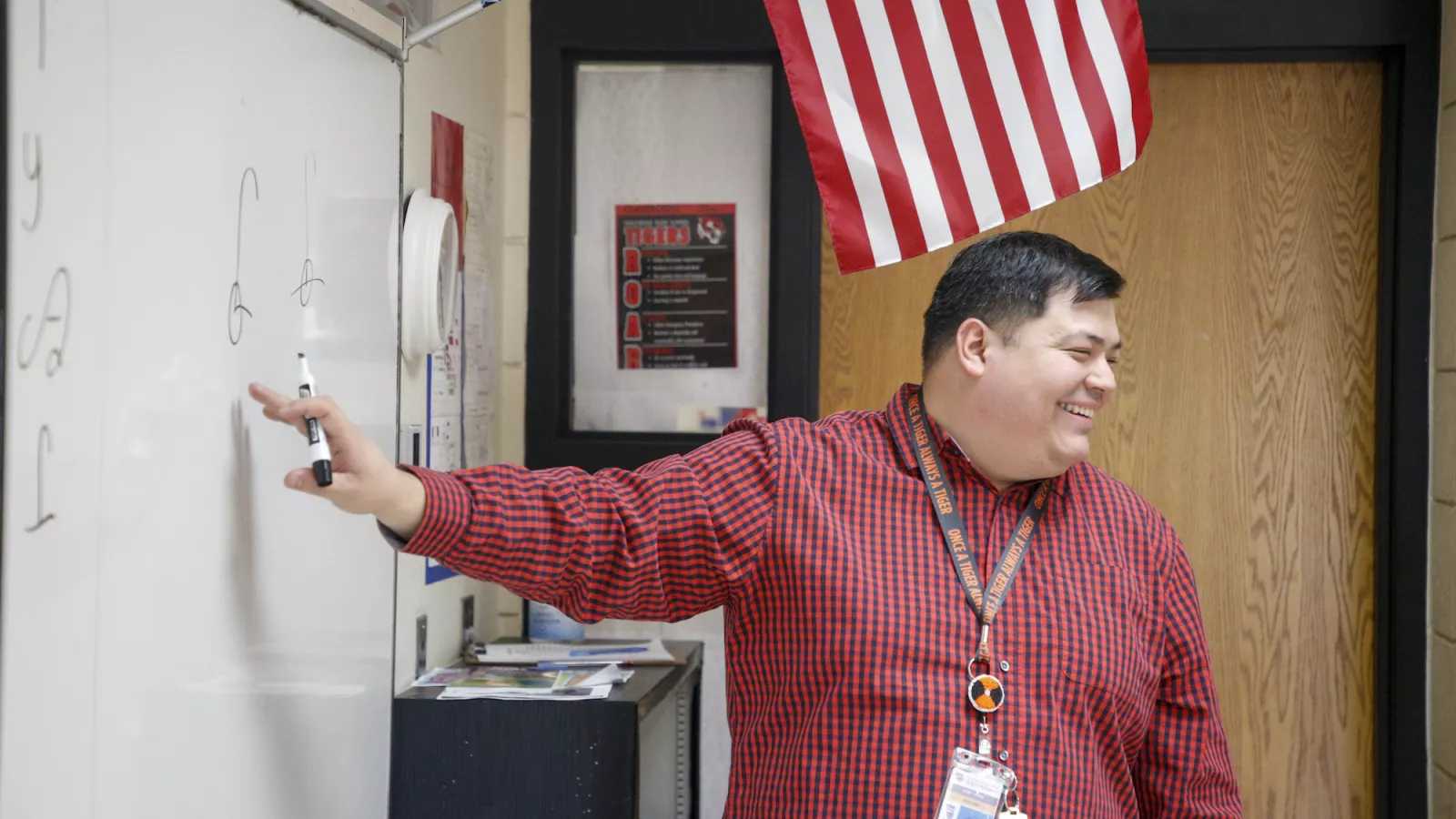

“How many of you are fry bread snobs? Like it has to be the right fry bread, or you won’t even touch it?” Cody Vann asks his Cherokee language students.

“Hot, fresh, fluffy,” suggests Vann.

A student interjects, “And a little greasy!”

“Did you say greasy? Greasy?” jokes Vann. “I will not eat your fry bread.”

Everybody laughs. Then, he gets serious.

“Listen to me,” Vann says, a first-year teacher of Cherokee language and culture at Tahlequah High School—a public school on the Cherokee Nation Reservation, in Oklahoma. “You guys are crammed with cultural information … that keeps us alive as Cherokee people.”

Whether it’s how to pull wild onions or basic Cherokee language, the things you know from your elders must be retained and shared, Vann says. “[It’s] important to the survival of our identity,” he adds.

Today, fewer than 2,000 of the 600,000 official Cherokee Nation citizens speak Cherokee. In 100 years, will anyone?

Vann fears the extinction of his father’s language may be inevitable. At the same time, Cherokee practices around food and plants, dance and pottery, or knapping flint into sharp tools are also endangered.

Vann’s efforts at Tahlequah—combined with those of a handful of educators at public schools across the nation—may be key to the survival of Native languages and culture. But preserving cultural knowledge isn’t only about the past. These programs have academic and social and emotional benefits for students as well.

“Students who have a strong sense of who they are, of identity, do better in school,” says Northern Arizona University professor Jon Allan Reyhner, who has written multiple books on Native education and Indigenous language restoration. “Basically, you want students [to be able] to answer the three basic questions in life: Where did I come from? Who am I? And, where am I going?”

You Matter. Your Culture Matters.

Historically, public education was a blight in Native communities. Starting in the mid-1800s, after the U.S. military ordered Native families off their lands and onto specific tracts, Native children were sent to government-run, English-only boarding schools. There, they were brutally punished—whipped, denied food, or confined alone—for speaking their language or engaging in Native cultural practices.

Students and families were traumatized, and Native language and culture were devastated. By the mid-1900s, roughly two-thirds of Native languages in the U.S. had died. Countless cultural practices were lost forever.

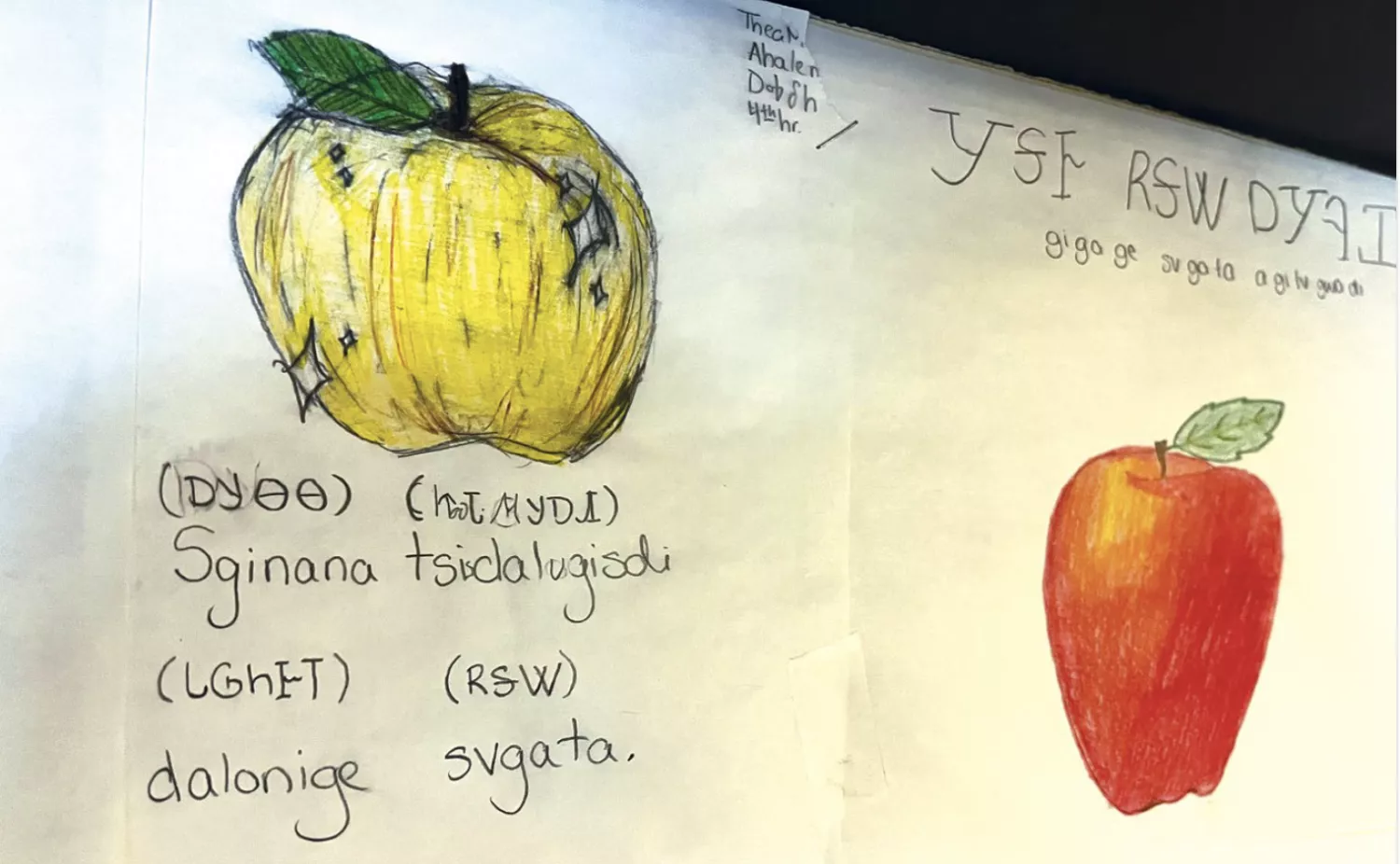

Today, public school educators and their unions are working to reverse the boarding school legacy. The Native language and culture classes that these educators teach—and the policies that NEA supports—send a powerful message to students: You matter. Your family matters. And your people’s language and culture areworthy of study and preservation.

This message is self-affirming, empowering, and very often leads to academic success. Indeed, research shows that Native students studying Native languages have better attendance and are more likely to graduate.

It’s also critical to mental health among Native teenagers. Research published in the journal Cognitive Development shows that Indigenous youth with less knowledge of their Native language are six times more likely to want to die by suicide.

This is why NEA’s Resolutions, which formally establish the union’s beliefs or positions, call for the “preservation of the Native languages of the Indigenous people of the Americas.”

The Stakes Are High. But So Are the Challenges.

It’s not easy to find a teacher like Vann. With the ongoing national teacher shortage, it’s a struggle for districts to find special ed teachers, never mind teachers fluent in endangered languages. At age 33, he may be the youngest fluent Cherokee speaker alive.

In Rapid City, S.D., school officials recently suspended a Lakota immersion program due to a lack of qualified staff. In Hawaii, state officials are offering $8,000 annual salary bumps to certified Hawaiian language teachers.

Once hired, Native language teachers face additional obstacles in finding textbooks, assessments, and other materials.

“We don’t have a pre-packaged curriculum delivered to us. It’s very hard work,” says Hawaiian immersion teacher Hope McKeen, who spends hours each week creating her own classroom materials.

Recently, the Hawai’i State Teachers Association (HSTA) created a committeeto inform the union’s work in Hawaiian education. It’s a major step toward organizing kumu (teachers) and strengthening HSTA’s advocacy for Ōlelo Hawai’i (Hawaiian language) and ike Hawai’i (Hawaiian culture, history, and practices) in schools.

In other parts of the country, however, where Indigenous language and culture teachers are rarer, it can be difficult for them to find each other, share resources, and advocate for what they do, says Christina Goodson, a tribal education specialist with the National Indian Education Association (NIEA), which partners with NEA to advocate for federal funds and resources for Native students and educators.

In Tahlequah, Vann is developing a curricula on his own, using what he learned through the Cherokee Language Master Apprentice Program, a selective program run by the Cherokee Nation. His prize possession? A Bible, translated and written in the 85-character Cherokee syllabary, invented by Sequoyah, in 1821.

Wake Up!

Vann grew up hearing Cherokee. His father spoke more Cherokee than English, and his grandmother was a monolinguistic speaker. As a child, he’d even hear the language in the aisles of the local grocery store, where old friends stopped to chat.

Today, those casual conversations are more than rare. Fewer than six of the remaining Cherokee speakers are under age 50. More common Indigenous languages in the U.S. are: Hawaiian; Din. Bizaad, the Navajo language, which has nearly 168,000 speakers, according to Census data; and Yupik languages, which are spoken by about 10,000 Yupik people in Alaska.

Most of the 150 Native languages still spoken in the U.S. have just a few hundred speakers left, according to Census data. As these elders die, their languages likely will, too. By 2050, maybe 20 Native languages will still be spoken, the Indigenous Language Institute estimates.

In the absence of language, it’s still possible to support Native culture, the educators suggest. Having more Native teachers, whether or not they speak a Native language, would be helpful. Earlier in Goodson's career, when she taught the Otoe-Missouria language to elementary students, she learned from that experience that it was important just “to be a Native person that Native students can see every day in a classroom.”

Less than 1 percent of U.S. public school teachers are Native, and only about a quarter of teachers in majority-Native schools are Native, according to NIEA data.

Union-led programs to develop more Native teachers, such as the Washington Education Association’s Future Native Teachers Initiative—which brings together Native students to explore careers in teaching—may eventually stem that shortfall.

Meanwhile, all educators, regardless of their race, can make sure Native people and cultures are included in classroom materials and standards.

“My biggest fear is to see Cherokee language die,” Vann says. He looks at his students—and his own six kids—and the time they spend on their phones, cultivating social media accounts and ignoring the real culture around them.

“I want to grab them by the shoulders and say, it’s dying. Your identity is in the midst of its death," he says. “Wake up! Do something about it.”

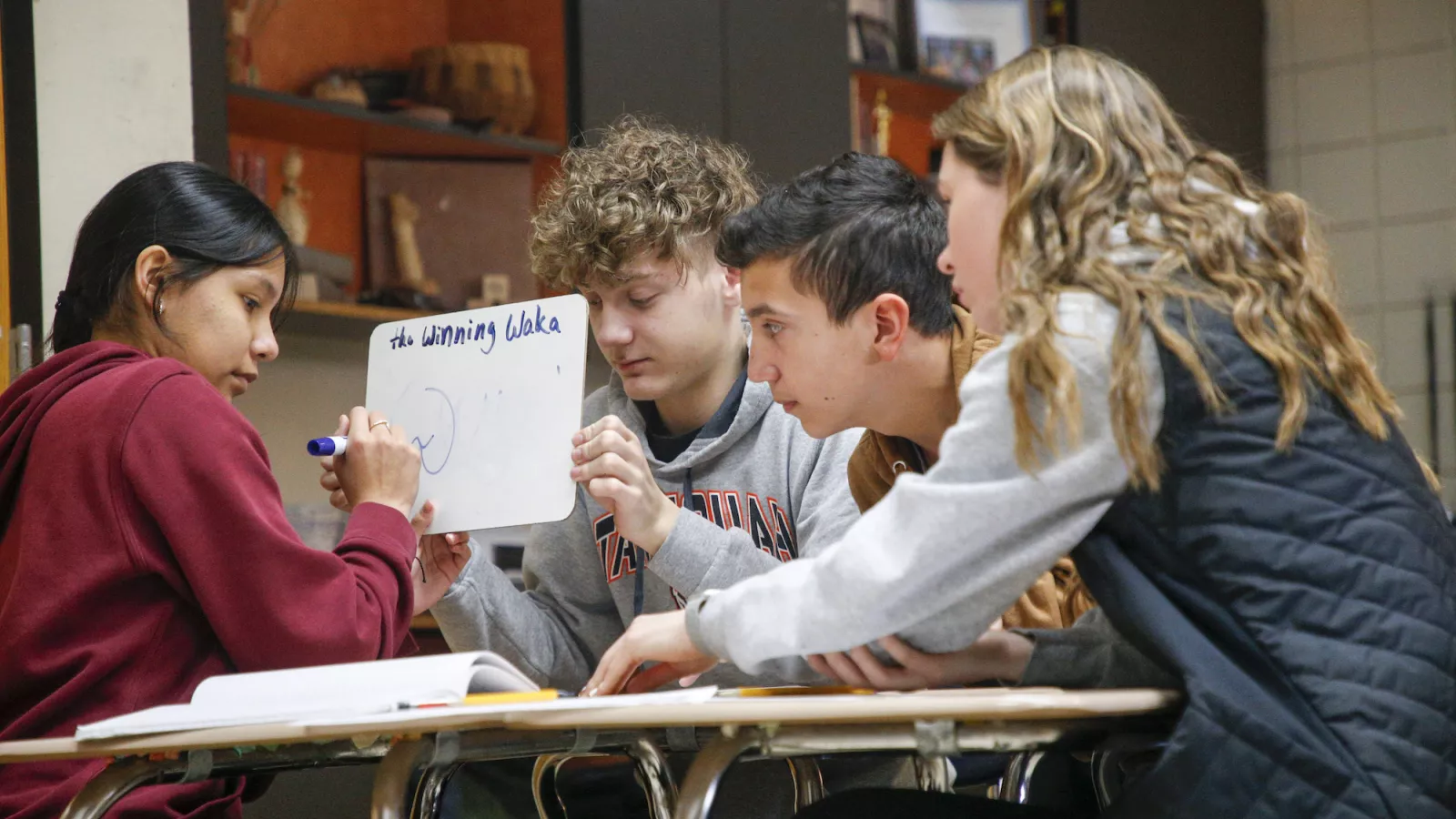

Storytelling Day in Cody Vann's Classroom

Part 1

Three students take turns telling a story that they made up. It’s about a girl who goes to a powwow, runs into Deer Woman on the way, and disappears—never to be seen again.

“Are you kidding? Deer Woman?! You’re gonna give me nightmares,” groans a classmate.

“What’s the moral of that story?” asks Vann. “It’s very traditional in Cherokee to have a moral.”

“Don’t go to powwows with Deer Woman!” says one student.

“Maybe tell somebody where you’re going?” offers Vann.

Part 2

A student talks about a Thanksgiving at her grandmother’s house. Her grandma cooked wild onions and kanuchi, a Cherokee hickory nut soup. After dinner, the student and her little brother played in the woods deep into the night, until they saw a skinwalker— a witch that can transform into an animal—and got scared.

Turns out, it was her cousin. The student’s grandmother had told her cousin to pretend to be a skinwalker so the kids would come running home. “There’s a reason us Cherokees grow up so skittish,” says Vann. “It’s Grandmas, right?”

Part 3

Vann tells a story, first in Cherokee, then in English, about walking through the woods with his Uncle Wayne. They found a patch of single-leaf plants. “There was no wind that day, but when we walked by them … they were shaking—a lot,” he recalls.

“Why are those plants shaking?” Vann asked his uncle.

“Son, that’s where the little people live,” his uncle replied. “You need to get away from them. … Be respectful while you’re in their home.”

“What’s the purpose of stories like this?” Vann asks. “Respect nature,” a student suggests.

Get more from