Janice Coleman was expecting celery when the boxes of fresh food arrived in her cafeteria at Riverview Elementary School, in Durango, Colo.

Just not quite so much celery.

“It was a box with 38 stalks. … I don’t know how I got it and didn’t know what to do with it all, but we figured it out,” she says. “We served some to the kids, used it where we could in our marinara sauce and other dishes, stored some, and donated some. I just can’t stand for food to go to waste.”

That’s just one small example of the multiple ways Coleman, who is the school’s cafeteria manager, makes sure she and her staff, as well as the students, use food efficiently. They also go to great lengths to reduce waste, compost, and recycle as much as possible.

Like many food service workers and other school support professionals, Coleman is at the forefront of implementing a growing number of green initiatives in schools nationwide.

“The success of waste reduction, recycling, composting, energy and water conservation, and other sustainable practices in K–12 schools would not be possible without the daily involvement of custodians, paraeducators, cafeteria staff, and other support employees,” says Dale Alekel, who is program manager for an ambitious Green Schools initiative in King County, Washington. The program works with 328 schools in the Seattle area to adopt environmentally friendly practices.

“[Support professionals] are the ones who often champion these practices, collaborate with teachers and administrators, and help to lead and engage students and fellow staff in taking steps toward sustainability,” Alekel says.

Support staff acknowledge that these programs often add new responsibilities to their already full plates. Bus drivers and maintenance personnel may have to learn new skills to work with alternative fuel buses, and custodians or cafeteria workers are charged with handling often poorly sorted recycling or compost material.

Building maintenance staff must work with new, efficient heating and energy systems or solar panels and be more conscious of air quality issues. And paraeducators often are responsible for encouraging students to follow sustainable practices.

“When I’m working in the cafeteria, I’m constantly monitoring the kids to make sure they put material in the right bins for recycling,” says Connie Jerman-Webb, an instructional aide for the Charles County Public Schools, in Maryland. “I like to remind [students] that the energy saved in one recycled can could run a video game for hours,” Jerman-Webb says.

Eco-Friendly Cafeterias

In Coleman’s cafeteria, the staff originally gave their compost to a local chicken farm. Now, they are working with a science teacher to develop a school garden. Along with sorting food materials, Coleman and her team compost the brown paper towels used in the cafeteria and make sure the cans and boxes are recycled, along with much of the lunchroom paper and plastic.

“My staff is really good about it, and I think it is very important. We all have to do what we can,” says Coleman, who is president of the Durango Education Support Professionals and credits the union with supporting her efforts. Andrea Cisneros, the cafeteria manager at West Woods Elementary School, in Arvada, Colo., is adamant about making her school more environmentally friendly.

“I’m obsessive about healthy meals and not wasting anything, because when I was a kid we didn’t have much, and I was literally getting food from a dumpster,” she says.

Cisneros has worked through the Jeffco (Jefferson County) Education Support Professionals Association, and in partnership with other organizations, to change district policy by lobbying the state legislature about the need for healthier school meals.

These efforts bore fruit, so to speak, when Colorado voters approved a healthy schools measure on the 2022 ballot, which will provide money for free, nutritious, locally sourced school meals.

“We’ve made real progress, but now I’ve also just decided to stop serving junk food,” says Cisneros, who says there are financial incentives for the district to use large food service providers rather than local growers and merchants. More revenue is also generated from high volume sales of pre-packaged, processed food, she adds.

Junk food isn’t only unhealthy, it also generates more waste. When students choose processed muffins and candy over more nutritious options, the packaging creates additional trash, and the healthier food often goes to waste.

“I want kids to eat a healthy meal rather than six cookies, which they’ll choose given the chance,” Cisneros says.

Environmentally friendly policies have also been implemented in the Oakland Unified School District, in California, where support staff is often charged with implementing the program.

“It often falls on their shoulders,” says Nancy Deming, the district’s sustainability manager.

These responsibilities can include composting or collecting students’ food bank donations,such as undamaged fruit or unopened packaged food. Some schools in the district are using milk dispensers, which reduce packaging and wasted milk, but also require cleaning, servicing, and refilling by the cafeteria staff.

Student Awareness

Support staff also play a key role in educating students about environmental issues, says Jerman-Webb.

“[ESPs] are the ones in the cafeterias who can make students aware of the waste that is created and how it can be reduced,” she explains.

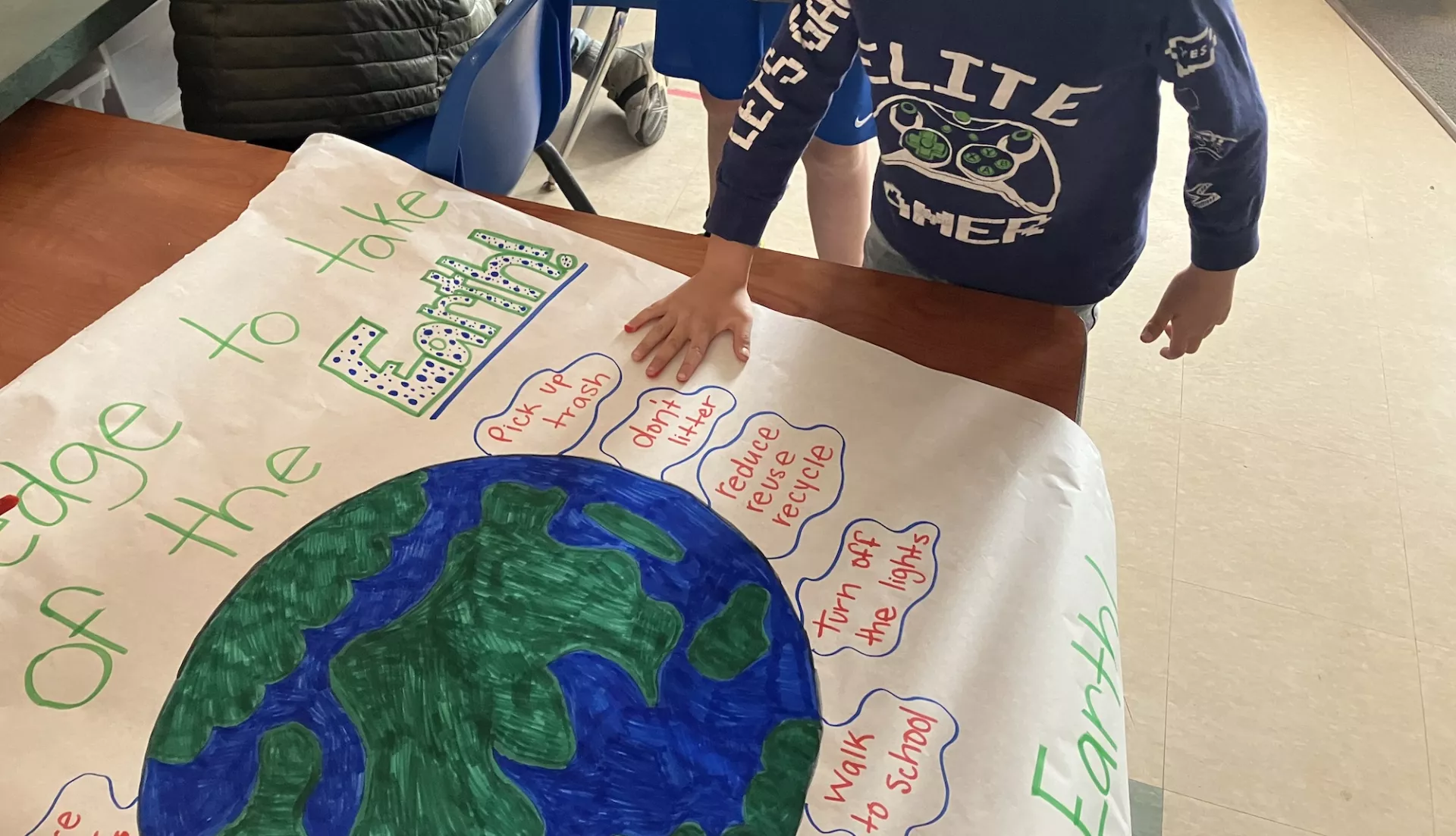

As part of these efforts, Jerman-Webb directs the Green Club at Gale-Bailey Elementary School. Students in the club learn about sustainable practices and undertake cleanup projects on the school grounds as well ason a nearby roadway and stream. The club members hear presentations about environmental issues and wildlife protection and discuss strategies to help. Jerman-Webb also challenges students to spread the word to classmates.

In Durango School District 9R, custodial manager Ron Reed takes a similar approach. An advocate for sustainability, he has established six green teams at district schools.

“Our building crews play an important role, obviously, but these are to be student-run efforts,” he says. “We want [students] to generate other programs … that help and create change. We want them to be visible so that other students want to join and help.” At Bethlehem Middle School, in Delmar, N.Y., the students in McKenzie Barrett’s special education classroom collect recycling during a free period, with ESPs guiding them.

“[ESPs] … are the ones overseeing the execution of this routine for the students,” she says. “Having familiar support staff to help these students is crucial.” Ann Ouellette, an aide in the classroom, says, “This is a good opportunity for the students to see school staff they don’t normally interact with, and [the students are] proud to be part of helping our school community.”

Cleaner School Buses

In Virginia’s Fairfax County Public Schools, support staff have been key in getting new electric vehicles on the road, says the district’s director of transportation, Francine Furby. The district currently has 8 electric school buses and will be getting 20 more soon.

“Having both the drivers and the maintenance people involved with the new technology has been very important to us,” she says.

“When you have new systems like this, they play a key role in planning for the change, implementing it, and then providing feedback when the inevitable glitches arise,” she explains.

In the bus depot in the Austin Independent School District, mechanic Alexander Dubon has seen the challenges of transitioning to alternative fuel buses firsthand. The district has propane and hybrid buses and soon will be getting electric buses, all requiring different maintenance skills and new training for Dubon and his co-workers.

“It is more work and new knowledge, but I’m glad to do it. We only have one planet, and if this contributes to saving it—it’s okay with me,” he says.