Key Takeaways

- As many as 3 million students disappeared between March and October 2020. When schools reached out to students and their families, they never heard back.

- Missing students are primarily from marginalized groups that often face barriers to their education.

- Collaboration between educators, principals, social workers, and community groups can help bring these students back into the classroom.

March 2020 was a terrifying time for educators as the realities of the pandemic emerged and state leaders made the difficult decision to close school buildings. After switching to remote classes, many educators were hit with another unfathomable reality: Some of their students had disappeared.

“It was really disappointing, because we had positive relationships with those students, and then they just disappeared,” says James MacIndoe, who teaches English at Standley Lake Senior High School, in Westminster, Colo. At the worst point, roughly 15 percent of his students had gone missing.

Countless educators like MacIndoe have worked to locate students who fell off the grid during the COVID-19 crisis. Precise data is hard to come by, but research by Bellwether Education Partners estimates that as many as 3 million students disappeared between March and October 2020. When schools reached out to students and their families—by phone, by email, and by snail mail—they never heard back.

Although most school districts have reopened in full or in part, the search for students is not over.

Students Unseen

Jefferson County Public Schools, where MacIndoe teaches, started the 2020 – 2021 school year with remote learning, and then went hybrid in mid-November. By spring 2021, the school building had opened for in-person learning for all students, with a virtual option—which about 40 percent of families selected. MacIndoe had roughly 100 students in his classes, but he still couldn’t locate 7 of them.

“I could never get a hold of any of those students or their parents,” he says. “I had students on my roster that I never saw.”

The number of students missing from his classroom by spring 2021 was about half of what it was the year before, but MacIndoe was deeply concerned for those few who were still completely disengaged from their education.

“We had positive relationships with those students, and then they just disappeared. … I had students on my roster that I never saw. ”

According to the Bellwether research, missing students are primarily from marginalized groups that often face barriers to their education, including students in foster care, homeless students, English language learners, students with disabilities, and students who are the children of migrant workers.

That tracks with the students MacIndoe lost.

“These families are facing so much stress they can’t provide the framework for these kids’ virtual learning,” he says. “For some of these kids, they are not in a good place in terms of their mental health, and can’t sit in front of a computer five hours a day.”

One of his students is in a particularly difficult situation. “She takes care of several younger children, and her mom has health problems,” MacIndoe says. “Normally, school would be her place to get away from those problems for a while, but during the pandemic she has basically become a caretaker forher family.”

Here to Help

The Robla School District, in Sacramento, spans five schools and serves grades pre-K–8. The families they serve are low-income, and many students are English learners.

When schools went virtual in March 2020, absenteeism was high, says Laurie Butler, a social worker in the district for 22 years. “We knew right away that we had to get to families and let them know we are here to help,” Butler says.

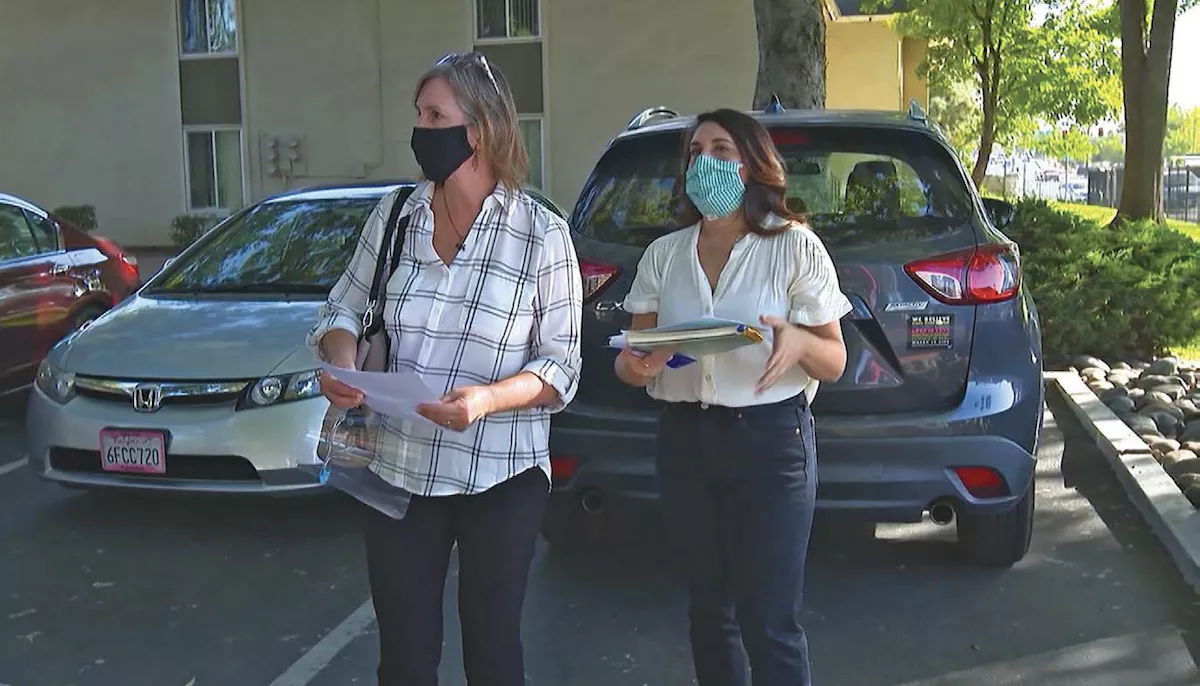

She met with her team, and quickly developed Student Find, a districtwide program to locate and assist families. They determined protocols for making home visits safely, equipping staff with masks, face shields, and gloves. They got the word out to teachers that they should alert the Student Find team if a student is chronically absent from class.

By early May, Butler and her colleagues were knocking on doors offering tech assistance, hot spots, advice on setting up children’s at home learning, and connections to social service agencies.

Elisa Olmo, another district social worker, teamed up with Butler to go door-to-door to help families. “This was very individualized work with each family,” Olmo says.

One family needed help getting on a waitlist for permanent housing after experiencing homelessness; others needed a Spanish-speaking contact.

“A lot of students were home alone, or an older sibling was in charge because their parents have to work,” says Butler. “You can’t tell a parent don’t work.”

Instead, Robla worked with a local non-profit, the Roberts Family Development Center, to open a learning hub where students could go four days a week for supervised online learning in a safe environment, with health protocols in place. The program provided transportation, breakfast, lunch, and an afternoon snack.

Butler calls the hub “a lifesaver” for many of her students.

The hub was still operating after Robla entered a transitional phase in the spring, offering two days of in-person learning per week.

“Our families have been so appreciative that we’ve had real solutions to bring to their doorstep,” Butler says. Both during the pandemic and moving forward, it is essential that there are staff able to go meet families where they’re at, says Olmo.

“It takes a lot of staff power to do home visits, but just look at how successful we can be,” Olmo says. “It’s a team effort between teachers, principals, social workers, and the community groups that want to help make sure that students don’t fall behind.