Key Takeaways

- Educators who are resigning from teaching are using the power of social media to air their grievances - and people and policymakers are listening.

- Later school start times may be benefitting the learning experience.

- The charter school industry can gain valuable lessons from the demise of a corporate giant.

The Upside of Teacher Resignation Letters Going Viral

In recent years, many resignation letters written by teachers have circulated rapidly. Most of the educators who wrote them never imagined that their musings—usually posted on Facebook or as a letter to the editor—would reach such a wide audience. But the potent combination of sadness, defiance, and a compelling dissection of what is wrong with public education—high-stakes testing, scripted curriculum, and punitive accountability measures—clearly resonated with a much larger audience.

Alyssa Hadley Dunn, assistant professor of education at Michigan State University saw the letters as a new “genre” of teacher public discourse deserving of further study.

Along with a team of colleagues and graduate students, Dunn examined 23 teacher resignation letters and interviewed eight of their creators. Overwhelmingly the missives attest to the lack of voice and agency that the teachers felt in policymaking and implementation.

“Educators know what needs to happen in the classroom,” Dunn says, “ but are not asked what they think. This adds up to a feeling that the knowledge they have makes no difference.”

Judging by the intense reaction, the letters may be giving educators a powerful public voice that they didn’t have before. On one hand, for the writers at least, gaining professional agency by leaving their job seems to be the quintessential Catch-22. But Dunn argues that the collective, visceral impact of their words is helping to build a wall of resistance to the misguided education policies that have made the system so oppressive.

“They’ve engaged in teacher activism and participatory democracy...that has allowed them to demonstrate their identities as writers, teachers, and activists while fighting for the profession they wish existed,” she says.

The lessons for administrators and policymakers are clear.

“There are many ways to give teachers a role in the design and implementation of policies at the school level—how they are talked about, how they are thought through, and how they are conveyed to students,” Dunn says.

Let Them Sleep?

An increasing body of evidence is showing how later school start times are making a difference in students’ lives, including improved educational outcomes and mental well-being.

Physicians have advocated for later start times for more than two decades, and the body of literature linking adolescent sleep with increased student success has only grown in depth and rigor.

A new study by Pamela McKeever of Central Connecticut State University, and her colleague Linda Clark, found that delaying high school start times to 8:30 a.m. and later significantly improved graduation and attendance rates.

School districts “set students up for failure by endorsing traditional school schedules,” McKeever writes, and this practice continues even in the face of mounting evidence supporting the benefits of a later start time. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that in 42 states, 75 to 100 percent of public schools start before 8:30 a.m. According to the CDC, school should begin no earlier than that time.

Early starting times are out of synch with adolescent sleep cycles. The adolescent body doesn’t begin to produce melatonin, a hormone linked to sleep cycles, until around 11 p.m., leaving adolescents with a limited window in which to obtain sufficient sleep.

In their study, McKeever and Clark looked at 29 high schools across seven states, comparing attendance and graduation rates before and after the schools implemented a delayed starting time. The average graduation rate jumped from 79 percent to 88 percent, and the average attendance rate went from 90 percent to 94 percent.

“As graduation rates improve, young adults experience less hardship after graduation, a lower chance of incarceration and a higher chance of career success,” McKeever told Reuters. Given the evidence, later start times could possibly serve as a mechanism for narrowing the achievement gap, says McKeever.

THE ARTS

Participation Remains Steady

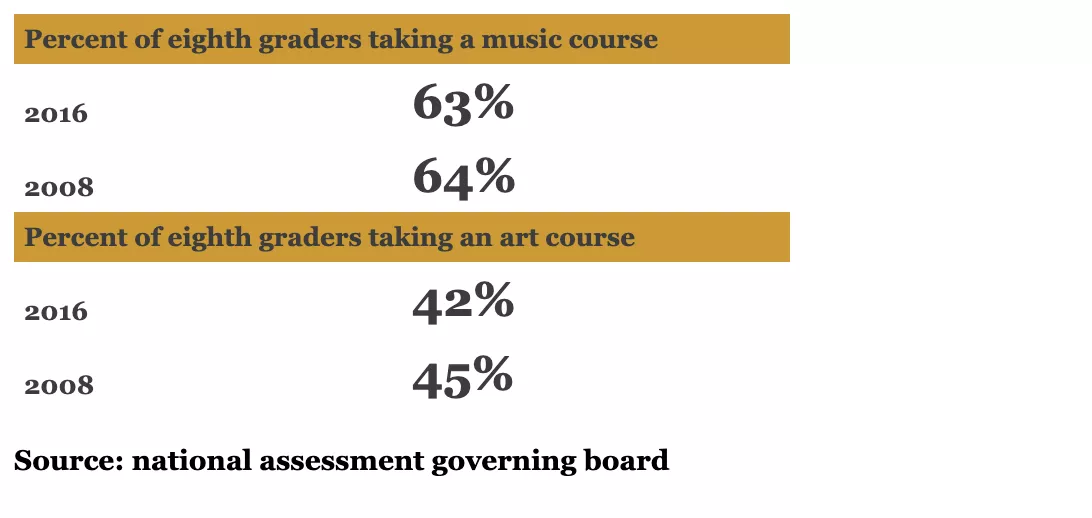

In April 2017, the National Assessment Governing Board released “The Nation’s Report Card: 2016 Arts,” the first assessment of eighth-graders’ performance in music and visual arts since 2008. Despite fears about the reduction in arts programs due to budget cuts, students’ overall scores and reported participation in the arts remained almost steady from 2008 to 2015.

| Percent of eighth graders taking a music course | |

| 2016 | 63% |

| 2008 | 64% |

| Percent of eighth graders taking an art course | |

| 2016 | 42% |

| 2008 | 45% |

Source: national assessment governing board

What the Charter School Industry Can Learn from Enron—Before It’s Too Late

The 2001 collapse of Enron, the Texas-based energy company, came to personify the overzealous, reckless brand of capitalism that in many ways came to characterize the decade.

Preston C. Green, professor of educational leadership at the University of Connecticut believes the same fraudulent acounting and business schemes that brought down Enron are being duplicated by for-profit entities that own and operate many charter schools.

Enron’s undoing can be traced to how it used “related-party” transactions to divert funds from the company to other business interests. The company concealed losses from these transactions from its investors, using deceitful accounting practices that somehow served to line the pockets of Enron’s top executives. A similar web of related-party entities, intricate maneuverings, and shady transactions can be found in the charter school sector.

Green says the watchdogs of the industry—governing boards, authorizers, state education agencies, and the U.S. Department of Education—have failed to “appreciate the fact that certain actors may need even greater surveillance than others.” The defect led to the abuses at Enron.

“In the case of Enron, the gatekeepers failed to consider the risks that Fortune 500 companies posed to the financial markets,” Green explains. “They wrongly assumed that these entities would play by the rules. As a result, Enron was allowed to engage in its illegal activities for several years without detection.”

The charter school industry is run by “educational entrepreneurs,” says Green. “These actors may also run businesses whose interests conflict with the charter schools that they are operating.”

Unless these practices are reined in, the charter school industry, like Enron, could soon become a “privatization crisis” case study, Green cautions.

EXPERIENCE

U.S. Students Still Taught By Certified and Experienced Teachers

Most U.S. students in public schools are taught by certified and experienced teachers, according to data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics. Roughly 94 percent of students were taught by a state-certified teacher in the 2011 – 2012 school year—the most recent figures available from the Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), which includes questions about the sampled teacher’s state teaching certification.

When it comes to actual years of experience, the same survey revealed that 80 percent of students had a teacher with more than 5 years of experience. Specifically, 23 percent were taught by teachers with 6–10 years of experience, 20 percent by teachers with 11–15 years, 23 percent by teachers with 16–25 years, and 14 percent by teachers with 26 or more years.

Should More Students Be Allowed to Skip a Grade?

Only about 1 percent of students skip a grade in school. According to a recent report by Johns Hopkins University, this number should be much higher.

“Millions of American K–12 students are performing above grade level and are not being appropriately challenged,” the report concludes. Not only does this deficit drag down a child’s intellectual development, the researchers warn, it is putting “the country’s future prosperity” at risk.

But Jessica Lahey, author of The Gift of Failure: How the Best Parents Learn to Let Go So Their Children Can Succeed, believes “gifted” is a term that is thrown around too often.

“The line between truly gifted and a parent’s subjective perception of gifted has blurred,” she explains. “In an age when “average” is a dirty word, more and more parents want to view their children as gifted and subsequently pursue grade acceleration as the next logical step. Truly gifted children are exceedingly rare, and acceleration should be equally rare.”

While very bright children understandably can get bored and frustrated when they are not academically challenged, “it’s incredibly important to consider both brains and social development when making this decision,” Lahey says.

Many parents, however, are resistant for these very reasons. Jonathan Wai, a research scientist at the Duke University Talent Identification Program, a nonprofit organization that works with academically-gifted youth, understands the trepidation, but argues that “the socio-emotional outcomes of those who grade skip or educationally accelerate shows that the impact is fairly neutral, overall.”

Of course, much of the research is based on statistical averages, meaning that some students will fare negatively and some will fare positively. But Wai believes that “at some point the academic need clearly begins to outweigh concerns about potential social/emotional impact.”

You Don’t Have to Live in Finland to ‘Teach Like Finland’

Like many U.S. educators, Timothy D. Walker thought the schools in Finland sounded almost “mythical.” The rejection of high-stakes testing, a curriculum based on critical thinking and problem-solving, smaller classes, the time reserved for collaboration between teachers—these are just few of the pillars of a system that has been heralded around the world. In 2013, Walker moved to Finland and was soon teaching fifth grade at a public school in Helsinki. As it turns out, a lot of what works in a classroom in Helsinki can work anywhere in the U.S. In his just-released book, Teach Like Finland: 33 Simple Strategies for Joyful Classrooms, Walker offers U.S. educators a lively and practical guide on implementing Finland’s best practices in their own classrooms.

What’s unique and innovative about Finnish schools seems out of reach to most U.S. educators. Did you want your book to serve as a sort of a bridge that teachers can use to bring at least a little bit of Finland into their classrooms?

Timothy D. Walker: Yes, that is exactly what I’ve tried to do in my book! Most United States teachers encounter a much different teaching context than Finland’s educators. For several years, I’ve kept a blog about Finnish education where I’ve highlighted lessons I’ve learned in Finland, but I admit that I’ve rarely blogged about what American teachers could actually implement in their classrooms.

In Teach Like Finland, I pushed myself to move beyond simply describing great practices in Finnish schools—I focused on suggesting strategies that can be easily wielded by U.S. teachers.

While I agree that transplanting the entire Finnish model is unsuitable for America, I think it’s misguided to think we need to have all or nothing. In my book, I’m focused on the little, practical things we can learn from Finland’s approach to education, in spite of the major differences.

What did you think about the strengths and weaknesses of American schools before you encountered the Finnish system?

TW: Before moving to Finland, I confess that I did very little thinking about how U.S. schools might compare to other schools around the world. I suspected that America had its share of “bad” schools, but I largely blamed the nation’s social inequality for their failings, not the educators. Also, I had a hunch that the world’s “best” schools could be found in the United States—institutions where children could encounter well-balanced curricula while learning in a student-centered manner with little stress.

Today I’m convinced, after teaching and living in Finland, that the glaring weakness in American education is, in fact, a basic matter of inaccessibility: too many kids in America lack access to decent schools.

If you had to pick one or two Finnish practices that American teachers would benefit most from adopting in their own classrooms, what would they be?

TW: I’d love to see American teachers adopt the practice of offering several short brain-breaks throughout the school day. Students in Finland can expect a 15-minute break for every 45 minutes of classroom instruction, and research shows that these kinds of breaks help students stay focused during class.

Or reading an interesting book at their independent reading level. Okay, it’s not free play, exactly, but choice time would provide students with several moments to get refreshed before the next lesson begins.

What are the lessons that Finnish teachers can learn from American teachers?

TW: Although Finland boasts a glowing reputation as an education superpower, it’s the United States, surprisingly, where many of the world’s most innovative pedagogies are conceived and developed.

Finland’s newest core curriculum requires that teachers move away from subject-based, teacher-centered instruction toward interdisciplinary, student-centered teaching. Finnish educators, undoubtedly, would benefit from visiting American schools where project-based learning, an innovative interdisciplinary model, has been successfully implemented for years.

I’d also like to see Finnish teachers emphasize social-emotional learning more systematically through implementing daily routines such as welcoming students with a handwritten note when they enter the classroom and offering a morning circle that builds a sense of community. I’ve found that many U.S. educators employ a social-emotional learning plan in their classrooms, and they rave about its importance.

Students Who Get News on Social Media Highly Support First Amendment

A 2017 Knight Foundation survey says teenagers who actively engage with the news across all platforms also strongly support the First Amendment.

Seventy-one percent of students who read, share, and comment about news on social media support the First Amendment, compared to 56 percent who never engage in news-related social media activities.

Percentage of students who strongly agree that “people should be allowed to express unpopular opinions” also: