Key Takeaways

- An NEA poll asks educators to specify which of NEA’s “Opportunity Dashboard” indicators they cared about the most.

- The “top dog/bottom dog phenomenon” for new middle schoolers is real and significant for students.

- According to PDK poll of the public, there is no clear consensus on the purpose of public education.

What’s the Best Measure of School Quality?

In 2015, former President Barack Obama signed into law the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which gave states the opportunity to realign how testing will be used in measuring schools and educators. Since its passing, many implementation plans have gotten underway.

Educators and Association leaders across the country have used the state-implementation process to inject their expertise into decisions that impact teaching and learning in the classroom. Along the way, they’ve pushed for their state’s accountability systems to include at least one indicator of school quality or success from NEA’s “Opportunity Dashboard.”

The National Education Association recently hosted an online poll that asked more than 1,200 educators to specify which of the “Opportunity Dashboard” indicators they cared about the most. Here are the results:

Learn more how you can get involved in the Every Student Succeeds Act at getessaright.org

|

85% |

Students’ access to fine arts, foreign language, daily physical education, library/media, and career technical education. |

|

73% |

Students’ access to health and wellness programs, including social and emotional well-being. |

|

65% |

Students’ access to fully qualified teachers, including Board-certified teachers. |

|

56% |

Students’ access to fully qualified school librarians/media specialists. |

|

54% |

Student attendance (elementary and middle school). |

|

54% |

Students prepared for college or career technical education certification programs without need for remediation or learning support courses. |

|

49% |

Students’ access to qualified paraeducators. |

|

48% |

School discipline policies and the disparate impact on students of color, students with disabilities, and students that identify as LGBT. |

Middle School and ‘Top Dog’ Status

Is there something inherent in the structure of a middle school that makes life more difficult for the average sixth grader? Yes, according to researchers in New York.

An 11-year-old entering a sixth-eighth grade middle school loses the “top dog” social status he or she had at elementary school. Suddenly, that student is a “bottom dog” and facing a change in status that can trigger academic and social drawbacks—drawbacks that are not experienced at the same level by a sixth grader at a K–8 public school, where they are more likely to be “top dogs.”

“The top dog/bottom dog phenomenon is real and significant,” says Michah Rothbart, an assistant professor of public administration and international affairs at Syracuse University. “It affects both student experience of the learning environment as well as academic achievement. It is not just about being new, but also something particular about one’s relative social position.”

At some point in an academic career, a student has to experience being a “bottom dog” but it’s a status perhaps best delayed until a student is a freshman in high school, when he or she is developmentally more suited to meet the challenges of being the youngest in the building.

“Our results suggest that middle school students’ experiences could be improved by structuring grade spans so they are longer and put students of these awkward ages closer to the top,” says Rothbart.

POLL RESULTS

What is the Purpose of Education?

Is the primary role of public education to provide rigorous academic instruction? Or is it to promote good citizenship? How about creating a skilled, career-ready workforce? According to the 2016 PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools, there is no clear consensus on the purpose of education. Fewer than half (45 percent) of the respondents say that academic achievement is the main goal and only one-third of that segment believe that “strongly.” Citizenship and preparing students for work were both cited by roughly 25 percent. When asked to choose, 68 percent of respondents said they would prefer schools to focus more on career/technical skills-based classes than to offer more honors or advanced academic classes.

The Lasting Impact of Mispronouncing Names

By Clare McLaughlin

Taking attendance at the beginning of class may seem a routine if not mundane task to many educators. But to students, their name can be a powerful link to their identity. Pronouncing students’ names correctly—during attendance, a classroom activity, or any other time of the school day—should always be a priority for any classroom teacher.

Overlooking or downplaying the significance of getting a name right, explains Rita Kohli, assistant professor of education at the University of California at Riverside, is one of those “microaggressions” that can emerge in a classroom and seriously undermine learning.

The effects can be long-lasting. In 2012, Kohli and Daniel Solorzano examined the issue in a study called “Teachers, Please Learn Our Names!: Racial Microaggressions and the K–12 Classrooms.” They found that the failure to pronounce a name negatively affects the worldview and social emotional well-being of students, which, of course, is linked to learning.

“Students often felt shame, embarrassment and that their name was a burden,” Kohli says. “They often began to shy away from their language, culture, and families.”

Kohli points out that most educators are not doing so out of disrespect, but tend to be confined by a monocultural viewpoint that makes it “more challenging to center cultures outside of their own.” Consequently, certain names sound unfamiliar and fall far outside their comfort zone.

My Name, My Identity Campaign

The “My Name, My Identity” campaign, launched in 2016, hopes to draw more attention to this issue. On the campaign’s website, teachers can access various resources on how to honor their students’ names. The campaign looks beyond the classroom to ask all community members to make a pledge honoring their neighbors’ and co-workers’ identities. Students and their families are also invited to share the significance behind their name on the “My Name, My Identity” Facebook page, or by tweeting @mynamemyid.

U.S. Lagging Far Behind on Early Childhood Education

Despite all the attention given to the issue, not much has been done in the United States to move the needle on universal access to early childhood education. Over the past few years, the campaign to expand it, however, has been global and most other industrialized nations are forging ahead.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), enrollment rates in early childhood or primary education programs rose across OECD member countries—from 54 percent in 2004 to 71 percent in 2014 for 3-year-olds and from 73 percent to 85 percent for 4-year-olds. The United States, on the other hand, has one of the lowest enrollment rates among OECD countries.

3-year-olds

The percentage of 3-year-olds (42 percent) enrolled in early childhood education in the U.S. (2014) versus the OECD average (71 percent).

4-year-olds

The percentage of 4-year-olds (68 percent) enrolled in early childhood education in the U.S. (2014) versus the OECD average (85 percent).

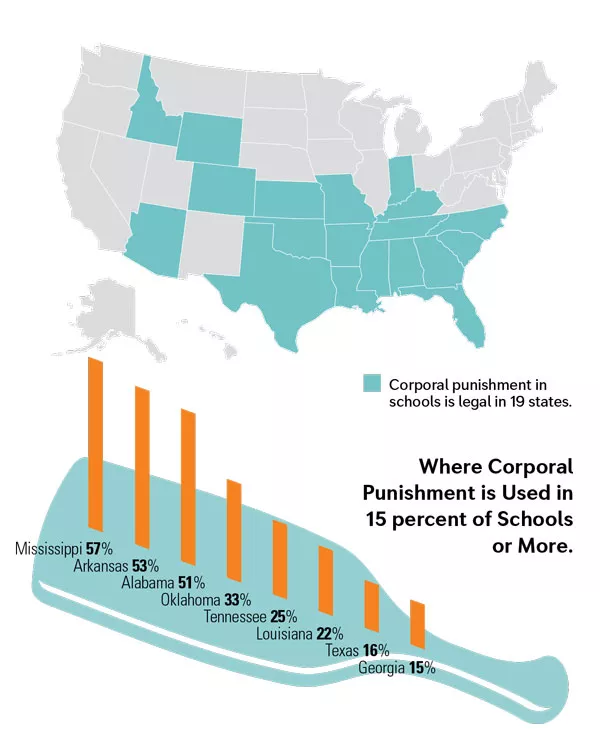

Which States Still Use Corporal Punishment?

In 1977, the U.S. Supreme Court legitimized the use of corporal punishment in schools by deciding that the practice did not qualify as “cruel and unusual punishment.” Despite the ruling in Ingraham v. Wright, corporal punishment—the use of physical force (usually paddling) on a student intended to correct misbehavior—would soon decline rapidly across the country. Between 1974 and 1994, 25 states would ban the practice, recognizing that it was an ineffective and inappropriate school discipline measure.

Since the mid-1990s, however, only five more states have joined those ranks, leaving 19 states that currently sanction the use of corporal punishment in schools. During the 2011 – 2012 school year, 163,000 schoolchildren were subject to corporal punishment. “Most people assume that corporal punishment has already been abolished across the U.S. Even people in states where it is legal do not always know it is so,” says Dr. Elizabeth Gershoff, a developmental psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Source: Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy—Gershoff, Font, 2016; Artwork: iStockPhoto

The Injustice Black Girls Face in School

Black girls make up 16 percent of girls in U.S. public schools, but 42 percent of girls’ expulsions and more than a third of girls’ school-based arrests. In her book, Pushed Out: The Criminalization of Black Girls in School, Monique Morris, co-founder of the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, shares the voices and stories of these girls, and also offers specific policy recommendations and strategies for educators.

What are the forces that have made these girls targets in their schools and communities?

Monique Morris: There are zero-tolerance policies in schools and school districts that have really removed the discretionary decision-making abilities of educators and administrators to respond to the core needs of students. And within this elevated climate of punishment, typical adolescent behavior, when exhibited by Black girls coming from communities under extreme surveillance, is very often misunderstood. Their actions are taken—they are misunderstood—as aggressive, even when they’re not.

How early in the lives of Black girls do these issues arise?

MM: Black girls are 20 percent of preschool girls, but 54 percent of the girls facing out-of-school suspensions in preschool. That number, and also the disparities around corporal punishment, are two points that show how schools are assessing threats among really young children. Those of us who have seen a 6-year-old throw a tantrum know they can throw a mean tantrum—but there are ways we can respond without pushing them out of school. What this says to me is that Black girls, from a very young age, are treated as disposable. What it also says is that we need to find ways to support them.

This summer at the NEA Representative Assembly, NEA members passed a policy statement on the school-to-prison pipeline, which calls for a multi-level approach to the issue, including better training for teachers in restorative practices and fewer school-based arrests and referrals. You’re also calling for comprehensive change—from state legislatures to the classroom down the hall. Can we talk about the breadth of change that needs to happen?

MM: Some of what advocates can do is move legislation, at the local, state, and federal levels. Those conversations are happening with folks trying to eliminate exclusionary discipline through legislation.

At the school level, what can happen is educators can refuse to refer students to law enforcement, and instead use a more empathic mindset. When an educator uses an empathic mindset, they can be single-handedly responsible for reducing suspension rates for Black and Latino girls by as much as 75 percent.

One teacher can make a difference. And not every teacher has to be that teacher. But when a child has at least one adult on campus who they can connect with, their likelihood of success increases and their likelihood of suspension decreases.

You just mentioned an ‘empathic mindset’—tell us more about that.

MM: It’s really about leading with love. When I talk to people about this, I often say the most radical recommendation I have is that educators lead with love, instead of punishment. The empathic mindset allows for the educator to see beyond a student’s actions, and to develop strategies to connect with students rather than just say, ‘This kid needs to get out of my classroom.’ The emphasis is: This kid has a need and how can I meet it? How can I understand them as a real person?

– Mary Ellen Flannery

Teacher Pay Penalty Growing More Severe

Educators in the United States are expected to be the best, but are nonetheless asked to withstand a severe “teacher pay penalty”—the loss of income they experience when choosing teaching over an alternate profession. How teacher pay stacks up to other fields is a major factor in the decision whether to become an educator.

“In order to recruit and retain talented teachers, school districts should be paying them more than their peers,” said Lawrence Mishel of the Economic Policy Institute. “Instead, teachers face low wages, high levels of student debt, and increasing demands on the job. Eliminating the teacher pay penalty is crucial to building the teacher workforce we need.”