Key Takeaways

- Public schools have a critical role to play in addressing the climate crisis.

- Educators are engaging students of all ages in creative lessons in climate science and environmental justice.

- NEA is advocating for high-quality professional development for educators to teach climate science, and state and local work around carbon-free schools.

There is a green future in which all of our students in every ZIP code live in healthy communities. They wake up in homes powered by clean energy, travel to school in electric cars and buses, and spend the day in modernized classrooms that have clean air and water. In this future, we teach all students the science of climate change and how to adapt to a warming planet. We empower them to make meaningful change in their communities.

We owe it to our students to fight for that future.

But for far too long, the issue of climate change has been sitting on the back burner as educators have been forced to confront more immediate threats to public education—from anti-union attacks to student poverty to a

global pandemic.

“We have to get students engaged in climate science, but that won’t happen if we just bombard students with terrifying scientific facts,” says Tim Swinehart, a social studies teacher from Portland, Ore. “We can teach it in a way that is personal and inspires action.”

With more wildfires, floods, extreme heat, and changing rain patterns in recent years, few could deny that climate change is already here. Another inconvenient truth: The effects of climate change are hitting Indigenous, Black, Brown, and low-income communities the hardest.

So far, education advocates have not had a clear role in addressing climate change. What we do next matters.

The fossil fuel industry has led a decades-long disinformation campaign to muddy the facts on climate change. And, unfortunately, certain politicians are deeply invested in preserving a system that’s riddled with inequities. But educators can make a difference.

Only 1 state, Illinois, has passed legislation to make their public schools carbon-free.

NEA believes our entire public education system must be a driving force in the effort to counteract these falsehoods, combat climate change, and create environmental justice.

NEA Today spoke with several educators who are teaching students to be climate savvy and build a greener future.

Teach hands-on ecology, early and often

Gabriel Knowles is a fourth-grade teacher at Helen R. Ealy Elementary School, which serves a lower-income, rural community in Whitehall, Mich. One of the first challenges, he says, is to help students get comfortable with bugs!

Knowles and his teaching partner, Brittney Christensen, established an outdoor, hands-on science curriculum that revolves around the courtyard garden. But the garden can be overwhelming for some students at first. So they start by practicing with a single flowering plant.

“Insects are a great indicator of how the environment is doing, but we have to get past the fear of bees before we take kids into the garden,” Knowles explains.

Once his students learn about pollination, understand that the bugs are busy, and see Knowles gently touch a bumblebee, they are ready to move into the garden. There they collect data, recording how many bees, beetles, and butterflies come to each plant.

His students have helped harvest seeds from native plants and created pollinator gardens at community spots such as a local library and a retirement home. Knowles and Christensen have also used some language arts time to have students write about their garden plans.

“Whether you have a big space for a garden or just one potted flowering plant to sit around, you can still have your students observe the process of pollination and collect and discuss data,” Knowles says.

“The sooner we start celebrating our students as little scientists, the more likely they will be to embrace that role in their future academics and in the world,” he adds.

Encourage critical thinking

It can be tricky to teach about environmental issues in a former coal town, explains Jacie Pressett, an agriculture educator at Carbon High School, in Price, Utah.

Her classes cover everything from veterinary science to natural resource stewardship. Her own family history in coal mining and ranching inspired her interest in ecology.

“My goal is not to tell my students what to think, it’s to teach them critical thinking skills so they can evaluate sources of information and draw their own conclusions,” Pressett says. Her advice? Respect and appreciate where your students come from, require them to research more than one side of an issue, and gently guide the conversation to what the data support.

“I can recognize that coal mining is an important part of our culture while talking to students about why it’s not sustainable,” Pressett says.

She has seen students broaden their perspective during hands-on projects like a river restoration or wildlife release she has organized in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“There’s nothing like hearing from a scientist from their hometown … to help students make connections to the natural world and our role in it,” Pressett observes.

According to research by NPR/Ipsos, 4 in 5 parents believe schools should teach climate change—and 86 percent of teachers agree.

Yet only 45 percent of educators polled say they currently teach climate change.

Why? Among the 55 percent of teachers who do not teach climate change, more than two-thirds say it’s not related to the subject they teach; a third worry about parent complaints; and around 20 percent say they don’t know enough about it to teach it.

That’s why K–12 Climate Action—a coalition of 22 civil rights, environmental, and education groups, including NEA—calls for a multidisciplinary approach to teaching climate science that is supported by high-quality and ongoing professional development for educators.

What Would Green Public Schools Look Like?

50 Million

100,000+

2 Million

480,000

7 Billion

Empower your students as activists

Climate anxiety is a real and profound issue among students. They know what a precarious position we’ve put them in, and some students are tired of waiting for us to hear their demands around climate action.

Few school districts have placed climate science and environmental justice as major curricular priorities, despite the outsize role these issues will have on students’ well-being.

That does students a disservice, says Tim Swinehart. “They are already experiencing the climate crisis, and it is irresponsible for us to just leave them hanging.”

Three-quarters of 15 to 17-year-olds in the U.S. think that climate change is a crisis.

Swinehart, who has been teaching for 16 years, is a social studies teacher who is often mistaken for a science teacher because he teaches environmental justice. That course wasn’t his idea—his students asked for it.

“The kids are scared, overwhelmed, and fired up,” he says. “But they are also natural activists, and they want to do something about it.”

Portland is one of the most progressive districts in the country on climate issues. In 2016, a coalition of teachers, students, and community leaders passed a climate justice resolution prohibiting the use of classroom materials that reinforce climate denial. The resolution also calls for presenting an accurate picture of climate change and a focus on environmental justice.

A critical part of environmental justice education, Swinehart says, is having students reflect on how climate change has affected them and others around them. Last summer, a severe heatwave brought three days of 115-degree heat to Portland, prompting Swinehart’s class to discuss how racist housing policies have left some people less protected from extreme heat. For example, neighborhoods where the majority of residents are People of Color are less likely to have shade trees and cooling green spaces and more likely to be near highways that generate heat.

Students also get energized by learning about people their age making a difference. Youth around the world have organized climate strikes, calling for bold action on climate change.

Young people in the U.S. have spoken out, too. They have written about their experiences with environmental racism and successfully advocated for laws and ordinances that improve local practices. They have also demanded that their school boards remove barriers to learning about climate science and environmental justice.

Understand environmental justice

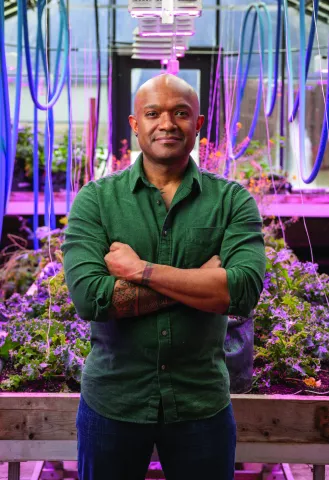

Jason Foster, a National Board Certified Teacher of biology at Evanston Township High School, in Illinois, cautions that educators must be clear about their intentions, understand intersectionality, and develop a “deep, personal understanding of justice.”

That means educators must have the ability to discuss the science of ecology, climate change, and how racism and poverty trap communities of color in perilous surroundings.

Foster says that when students at his previous school, Niles West High School, in Skokie, Ill., challenged him to explain how science lessons were relevant to their lives, it made him question his teaching practice. He thought about the science topics that he found most interesting and how he could bring those topics to the classroom.

“We’re getting to the point that people of color are struggling in some parts of the country to get clean air and water,” Foster says. “And here we were living very close to these textile factories, and we decided to explore the ecosystem there to look for potential dangers.”

His students took water samples and found anomalies among small crustaceans called daphnia. They wrote letters to textile companies asking how the businesses were protecting waterways and the animals that live in them. The students received an array of responses, ranging from honest and earnest to defensive and rude.

Then they contacted local and state politicians to inform them of what they had found. Some of the lawmakers sent templated responses, but others sent personal and appreciative replies. And U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky said she was exploring if companies could be charged with hate crimes when they knowingly pollute neighborhoods that are home to communities of color.

“When we received her letter, my students were like, ‘I’ve never had that happen before,’” Foster recalls. “I was like, ‘I’ve never had that happen before, either!’”

He often gets queries from fellow educators who are interested in developing justice-centered science units.

“I always start by saying this work is a marathon, not a sprint,” Foster says. “Keep reading materials to help you reflect on your own practices. Keep thinking about your own blind spots regarding racial justice, social justice, and intersectionality. You’ll find ways to naturally apply what you’re reading to your curriculum.”

Elections Matter for Progress on Climate Change

To lessen the worst effects of climate change, policymakers at every level of government must advance climate-friendly policies within the

next five years.

Here are just a few examples of what can happen when pro-public education and pro-environment candidates win elections:

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed legislation last year that made his state the first to commit to carbon-free schools. The Illinois Education Association projects that the legislation will save schools almost $5.2 billion over 25 years.

Carbon-Free and Healthy Schools is spearheading this work in Illinois and across the country. The labor-led initiative aims to create good union jobs and make schools energy-efficient, healthy spaces. NEA affiliates—including locals in Connecticut and Wisconsin as well as state groups in Illinois and Maine—are playing pivotal roles in these campaigns.

Progress is also being made in New Jersey, where Gov. Phil Murphy—supported by the New Jersey Education Association in both of his elections—worked with educators to create standards that include climate change in every grade level and subject area.

Elsewhere, educator unions are advocating for professional development on climate science and stronger policies on teacher preparation. But none of this can happen unless we elect legislators who support public education and believe in climate science.