Not only do some Arizona teachers have to contend with mice in their classrooms, they also have to buy their own glue traps.

Not only do some Arizona teachers have to contend with mice in their classrooms, they also have to buy their own glue traps.

Classroom globes that spin to reveal two Germanys, antiquated plumbing that regularly floods a school hallway also known as the “poo pod,” decades-old textbooks that overlook the last 10 elements added to the periodic table or call Ronald Reagan our current president—this is just some of the evidence of how Arizona lawmakers have neglected their public schools.

There also are the 48 students crammed into their high school English classroom, and the elementary school counselor who cares for 1,430 children.

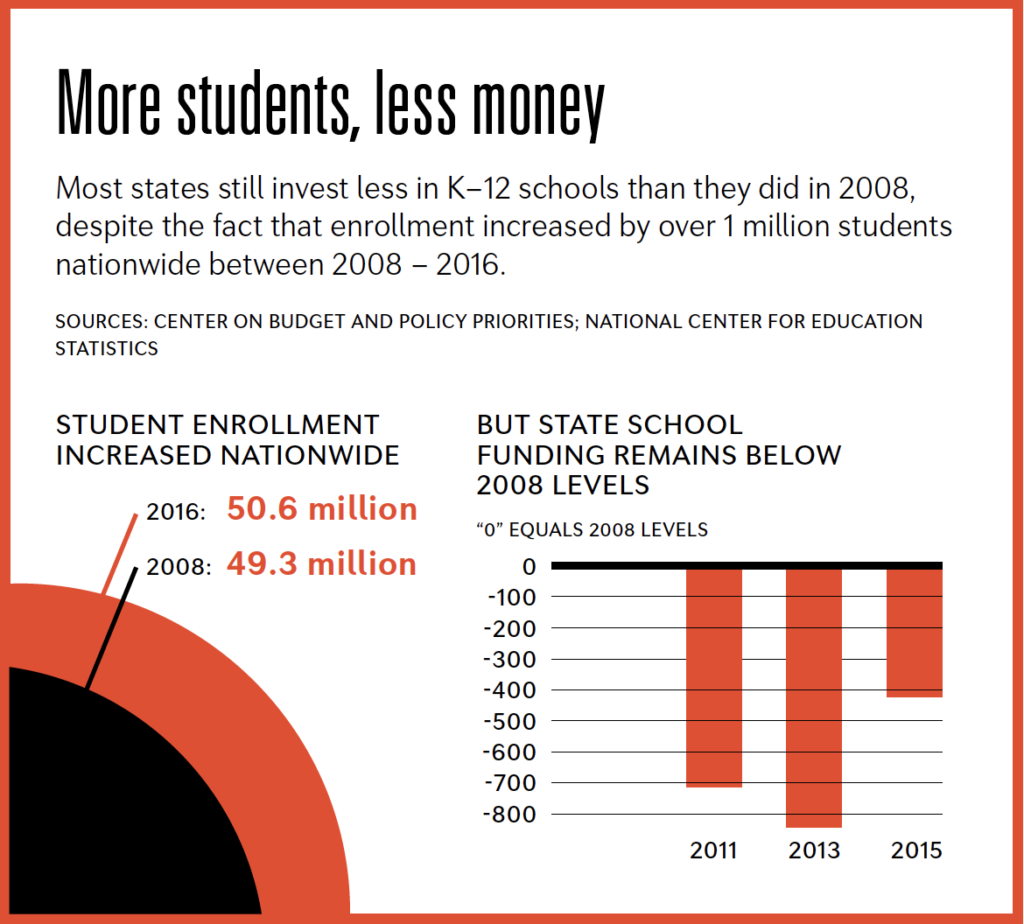

No state in the nation has cut K–12 funding more than Arizona, where lawmakers slashed school support by 36.6 percent between 2008 and 2015, according to the non-partisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). This year, school funding is 13.6 less than in 2008. Even as the state’s economy rebounded from the Great Recession, Arizona lawmakers opted for corporate tax cuts rather than investments in public education. Now Arizona students are paying the price.

“My students—and all students in Arizona—deserve more. They deserve more. They deserve to be learning in a fully funded classroom,” says kindergarten teacher Amy Ball, who has taught for 12 years in central Phoenix. “Every single student in Arizona deserves to have the most opportunities for success.”

The state’s educators aren’t taking it anymore. In late April, about 75,000 Arizona Education Association (AEA) members and allies held the largest educator walkout in history, flooding the streets in Phoenix to demand more state funding.

“I have spent 30 years in education and in that time we’ve seen cut after cut after cut and excuse after excuse. We’ve absolutely had enough,” says Phoenix technology specialist Thomas Oviatt, an educator for 30 years.

“Not only do I think Arizona students deserve better, I think every student deserves better. Arizona is a symptom of what’s been happening across the nation,” he says. “Every one of our students have been robbed of funding for decades.”

“Not only do I think Arizona students deserve better, I think every student deserves better. Arizona is a symptom of what’s been happening across the nation,” he says. “Every one of our students have been robbed of funding for decades.”

Oviatt is right—the education funding crisis isn’t just Arizona’s. In 2015, 29 states provided less school funding than in 2008. Since state funding fuels nearly half of the nation’s K–12 spending, these cuts have huge implications. They force school boards to either cut programs and hike class sizes, or raise more money locally. But for low-income communities especially, there is no choice. They must cut. And, research shows, those cuts do affect student achievement.

Educators across the nation have had enough. In what NEA President Lily

Eskelsen García has called an “Education Spring,” enormous rallies, walkouts, or strikes were held this spring in Oklahoma, Colorado, Kentucky, and most recently North Carolina to demand state lawmakers fulfill their promises to children.

Many were inspired by West Virginia Education Association members, who led a nine-day strike in February that closed public schools in every one of the state’s 55 districts.

Many were inspired by West Virginia Education Association members, who led a nine-day strike in February that closed public schools in every one of the state’s 55 districts.

“This is an absolute movement...and it’s not just one state,” says Eskelsen García. “Talking to legislators isn’t working. It’s like talking to a wall. We have to get the public’s attention. We have to rally. We have to be in the streets.”

The school funding crisis, says Eskelsen García, is a “man-made crisis” that lawmakers created and that they absolutely can fix—if they choose to.

In fact, in Arizona and elsewhere—Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Oklahoma—state lawmakers have opted to enact tax cuts that cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

This is money that could have paid instead for lower class sizes, current technology and textbooks, or even a fifth day of school in the hundreds of districts that have been forced to cut back to four.

Mice, Mold, and More

With photos shared on social media, teachers and education support professionals have pulled back the curtain on classroom conditions that have shocked parents and community members.

In Oklahoma, where lawmakers cut K–12 funding by more than 15 percent between 2008 and 2015, the pages of 1990s textbooks are held together with duct tape. Classroom chairs and desks are broken. Class sizes are outrageously large.

In Arizona, where some schools restrict the use of air conditioners to 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., and daytime temps can top 110 degrees, one teacher made her own homemade air-conditioner with a Styrofoam ice cooler and electric fan. Meanwhile, school librarians haven’t had money to buy new books since 2008. (Do Arizona kids think there’s just one Diary of a Wimpy Kid? Since 2008, Jeff Kinney has published 12 sequels!)

In Colorado, more than half of school districts have switched to four-day weeks to save transportation costs. Art, music, physical education, world languages, high school journalism, and more—in many states, these classes should be on an endangered or extinct species list.

Troubling trends in state funding explain why educators and allies have taken to the streets to demand more for schools.

In these states, pay is not the issue that has driven educators to the breaking point, but it is a fact that their pay is abysmal. In Oklahoma, there’s a teacher who sells his blood to help support his family. Everywhere, teachers work late into the night as Uber drivers or restaurant servers.

In Arizona, the weeklong walkout ended in early May after Republican Gov. Doug Ducey signed a bill that he claimed would give teachers a 20 percent pay raise. (AEA’s calculations say the money adds up to less than a 10 percent raise, and union leaders point out it doesn’t provide a dime for support staff.)

In Arizona, the weeklong walkout ended in early May after Republican Gov. Doug Ducey signed a bill that he claimed would give teachers a 20 percent pay raise. (AEA’s calculations say the money adds up to less than a 10 percent raise, and union leaders point out it doesn’t provide a dime for support staff.)

Arizona educators aren’t satisfied. Their movement isn’t about pay. It’s about funding. They’re committed to fighting for more money in their classrooms—for their students—and they are prepared to set their next battle at the ballot box.

In Oklahoma, educators ended their week-long strike in mid-April when lawmakers voted to override Republican Gov. Mary Fallin’s veto of the budget and tax bills, which combine to modestly fuel an increase in state K–12 investment.

Through their persistent presence in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Education Association (OEA) members won a pay bump for teachers and support professionals. Even more important, they won the first state tax increase in the past 28 years.

This is new, recurring revenue for Oklahoma classrooms, points out OEA President Alicia Priest, and the thousands of OEA members and parents who worked for it “should be overwhelmed with pride.”

But is it enough? No.

“They say Oklahoma students don’t need any more funding, and they’re wrong,” says Priest. OEA members now will turn their attention to state elections in November. “The state didn’t find itself in a school funding crisis overnight. We got here by electing the wrong people to office.

“No more,” she promises.