Until age 22, Derek Black was the chosen heir to the white nationalist movement. The son of Don Black, founder of the massive hate site, Stormfront.org, and godson to former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke, Black grew up in a world of racists—and he embraced it. The creator of a website for “proud white children” and the founder of a 24-hour radio network for white nationalists, Black pioneered the idea of “white genocide,” or that white people in America are victims, not perpetrators, of racism. Duke called him “the leading light of our movement.”

Then he went to college.

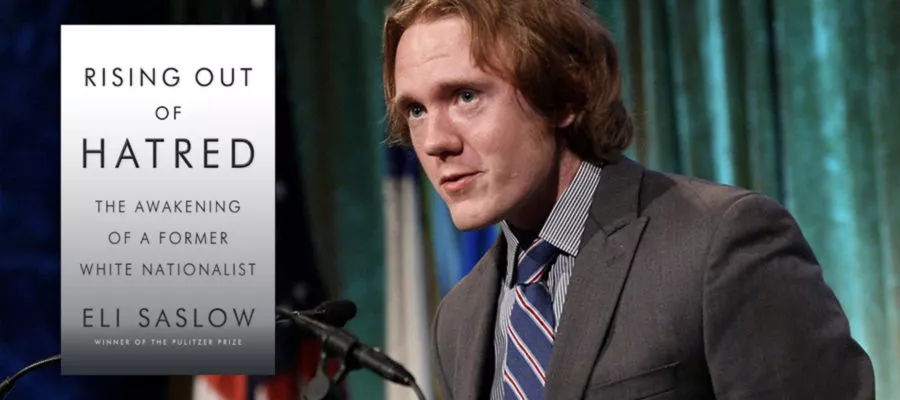

Recently, NEA Today spoke with Eli Saslow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Rising Out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White Nationalist, about Black’s renunciation of racism, how higher education played a role in the evolution of his thinking, and whether we can learn anything from Black’s story as we confront an emboldened white nationalism movement.

How did you hook up with Derek Black?

Eli Saslow: I first heard about Derek when I was working on a story about Dylann Roof. [Editor: Roof is a white supremacist who shot and killed nine people during a prayer service at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015.] Roof had been on Stormfront and because I was writing about it, I went on Stormfront. And, of course, I found this horrifying celebration of what Roof had done, but the biggest discussion thread was about Derek. I was fascinated. He’d made himself difficult to find—he’d switched his names and moved across the country—but I had some resources to track him down.

If a person like Derek, who was raised in this insular world with the specific intent of someday leading the white nationalist movement, if he can move that far to the other side, then it seems like other people also are capable of moving and changing in small ways, and this is particularly true in college."

The first time I got in touch, he was unequivocal: he did not want to be written about. I think he was hoping that white nationalism was this thing he could just leave behind and it would go away, which was incredibly naïve. We stayed in touch, and during that year, the far right was rising in Europe and the rhetoric that Derek had worked to mainstream was surfacing around the presidential campaign here. It was a mutual thing: I was telling him that, if he ever wanted to tell his story, this was the time, and I think Derek was feeling increasingly culpable and guilty about what was happening around him…It was a slow evolution and it took a long time for us to build trust. At that time [around 2016], he wasn’t a white nationalist anymore, but he was unsure of how public to be in his anti-racism.

I read the book, looking for ways that higher education impacted Black’s thinking…

ES: There was plenty to find! Both in the actual academics of the classroom and in the fascinating culture of that campus. [Editor: Black graduated from the New College of Florida (NCF), one of the 12 campuses in the State University System of Florida.] Where I live, in Portland, I sometimes work at Reed College, which may be similar to NCF in terms of politics, there is constant debate about whether to use civil discourse or civil resistance, and it’s an either-or, one thing or the other. In the book, it’s both. Both are absolutely necessary. Derek understands the value of civil discourse in his life, but he’s only open to conversations that challenge his beliefs because of the civil resistance that isolates him on campus. And those conversations were informed by what they were learning in their classrooms. Alison almost weaponizes her “Stigma and Prejudice” syllabus.

Are these campus conversations still possible today, when we’ve got sites like Professor Watchlist asking students to report their professors for “liberal thinking,” and so much uncertainty about safe versus free speech on campuses?

Are these campus conversations still possible today, when we’ve got sites like Professor Watchlist asking students to report their professors for “liberal thinking,” and so much uncertainty about safe versus free speech on campuses?

ES: A lot of things work to stifle conversation. The country is so polarized, and people are so far apart and hesitant to approach the divide. I guess the truth is I don’t know if it’s still possible, although I think so. It hasn’t been that long since Derek was at NCF, and the divides were very large on that campus.

I’m hesitant to talk about the book as a how-to guide for changing anybody’s mind. It took two years and incredible acts of personal courage to change Derek’s thinking. From James Birmingham saying we need to shut down the school, to Matthew, who says I’m going to befriend Derek, invite him to dinner every Friday for two years, and never talk about it, to Alison, who goes undercover to white nationalism conferences and engages in scientific debate with Derek for years about the science of race — obviously, it was not easy to change Derek’s mind. The story is unique, but I hope there are things that people can take to have conversations about this stuff. If a person like Derek, who was raised in this insular world with the specific intent of someday leading the white nationalist movement, if he can move that far to the other side, then it seems like other people also are capable of moving and changing in small ways, and this is particularly true in college.

Derek’s hometown, West Palm Beach, is a diverse community, too…

ES: It’s super diverse, and I certainly listened to Derek’s father, Don, when I was there, complain about that, in his ways, all the time! Derek was homeschooled. He was pulled out of school in second or third grade, and he was spun a story of why diversity was bad, of how he was surrounded by a lesser gene pool. They were mad because he was taught the version of American history that says everybody is equal, and a scrubbed version of Thomas Jefferson, not the white nationalist Thomas Jefferson that white nationalists know. They turned the idea of public education, in Derek’s thinking, into another example of why multiculturalism doesn’t work. If he’d been older, in high school, and able to see things for himself, he may have been able to come to his own conclusions.

Derek’s story feels like a victory, but it’s the story of just one racist, albeit a racist with a very high profile, changing his mind and heart. Derek himself acknowledges the existence of structural racism, a much bigger issue than any one person.

ES: One racist changing his or her mind matters, but it does not solve the incredibly embedded problems that this nation faces in terms of structural racism and systemic white supremacy. One of the things that I hope is there in the corners of the book, and that I hope Derek can continue to speak to, is how we can understand the systems of white supremacy. Derek spent the first part of his life [on his radio show, and at white nationalist conferences and “message trainings”] in ways that were useful to mainstreaming that ideology. The polls today are scary—more than half of white people believe that white people suffer racism more than people of color. That’s bananas!

Eli Saslow, author of "Rising Out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White Nationalist"

Eli Saslow, author of "Rising Out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White Nationalist"

Derek and other white nationalists were very effective in figuring out how to sanitize this ideology from its history of real violence, and instead talk about all the ways that white people are under attack in this country, talk about white genocide, talk about building a wall… Derek’s conclusion, which is certainly my own conclusion, is that the only way for our country to face its racism is to stare into it. We can’t just say ‘we believe in equality and racism is bad,’ we need to confront it.

Higher education is critical to that. Derek would not have left white nationalism if he hadn’t gone to college. I say that because he says that. It’s an incredible time of possibility for people to change their thinking. The possible conversations and interactions in diverse spaces, inside and outside the classroom, don’t happen very often in other times in your life. After college, we go back to our silos.

What’s Derek doing now?

ES: He’s in his last year of the Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago. I think he’s very good at what he does, and his original research in the field of Islamic medievalists is considered excellent. I think he feels a little bit torn these days. It is important to help people reimagine history in the ways it really was, but he also understands that he has a pinpoint, crucial understanding of America’s super-problematic white supremacist history and the ways that this administration and the far-racist fringes of the right can capitalize on that history to create more racial polarization. This summer, he was a consultant at Facebook helping them deal with polarization, but also at the same time reading 20 Islamic texts toward his PhD.

He feels haunted by the fact that he spent the first 22 years of his life spreading these ideas…he’s got a lot to figure out. How to forgive himself, whether to forgive himself, and how to engineer the rest of his life where he feels like he’s doing something important and purposeful.

Bottom line, what do you want people to walk away from the book thinking?

ES: Parts of Derek’s story are very hopeful. It’s fantastic that he emerged from it. Somebody who was going to be very important to the white supremacy movement is now activated to work against it. And that matters. But his story is set against incredible darkness. This ideology is growing. More of the country feels more comfortable in speaking in racially coded ways, and these beliefs are on the rise. White nationalists have been so effective at mainstreaming this sense of ownership among white people of this country, like ‘this country belongs to you! And now it’s something you don’t recognize! Let’s restore it to greatness!’ Unless we really look at that, acknowledge it, and begin a conversation about how, as a country, to fully activate against it, that stuff is only going to fester. I hope there’s enough hope in the book to give people energy to do that. Civil discourse and outreach has some possibilities. But it’s not an easy road.