Key Takeaways

- The pandemic has affected every area of public education and put a spotlight on the strengths and challenges of our schools.

- With the help of their union, educators are applying the lessons learned this past year as they plan for the future.

From the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, just over a year ago, educators have shown courage, creativity, and determination in helping their students and colleagues through the most difficult time of their lives.

This collective experience has changed us as human beings and has dramatically altered the way we teach and learn. And many of these changes—both good and bad—will likely impact K–12 education for years to come.

As we dare to look ahead, your voices will be more important than ever in ensuring that all students get the education they deserve. Read on for 10 ways the pandemic is affecting public education.

1. Educator Workload

Crushing educator workload is nothing new. And it has only intensified during the pandemic. As difficult as the last year has been, it has also reminded educators of the power of collaboration and collective bargaining—especially when it comes to keeping their workload under control.

In Upper Moreland, Pa., for example, collaboration between the union and the district allowed them to navigate the pandemic as successfully as possible—and emerge stronger.

“Our board and our superintendent made it clear that every stakeholder is valued, every opinion and emotion is valued, and even if we don’t all agree, we all can respect one another,” says Shannon Sullivan, president of the Upper Moreland Education Association. The district didn’t require teachers to be in school to teach. Instead, administrators trusted teachers as professionals. It wasn’t about where they teach, but how they teach, which should be their choice, Sullivan adds.

In California, the San Juan Teachers Association worked with district administrators to draft guidelines for teaching “essential standards,” rather than mastery of all the standards—recognizing the unprecedented situation and the overwhelming demands on educators.

And Ohio special education paraprofessional Andrea Beeman, who is president of the Maple Organization Support Team, worked with her union leadership to ensure that none of her colleagues lost jobs or hours.

Beeman also worked with the Maple Heights school board to ensure that paraprofessionals were able to participate in online learning. And she drafted a memorandum of understanding that allowed education support professionals (ESPs) to continue working by distributing meals and learning packets and conducting wellness checks.

“Throughout this pandemic, unions and their districts have successfully negotiated to address critical issues facing educators and students,” says Dale Templeton, director of NEA’s Collective Bargaining and Member Advocacy department. “It is critical they continue to engage educators and their unions in the plans and decisions they make to open schools safely and equitably.”

—Cindy Long

Learn More

Learn more about the strongest and most empowering way to give educators a voice in advocating for great public education for every student.

Say Hello to the New NEA Mental Health Program

- Get started

2. Student Learning

The COVID-19 pandemic created challenges for every learner, but according to some estimates, students of color could be 6 to 12 months behind, compared with White students, who are 4 to 8 months behind. A lack of technology, higher rates of coronavirus infection, job loss, and food insecurity are just some of the struggles impacting communities of color and their education.

For many students, the struggles were insurmountable. Some students missed days, even weeks, of distance learning as they scrambled to find devices and connectivity. Others remained unreachable, despite educators’ best efforts to locate them.

“I spent a lot of time missing and worrying about my students,” says Sheree Fagin, an elementary school teacher in South Pittsburg, Tenn. “We live in a poor area. Many of our families don’t have internet access.”

Even if they did have devices or access, they may not have had a place to study at home. “Many have chaotic home lives,” says Samantha Bean, a high school teacher from Gardena, Calif.

But the pandemic has also brought an opportunity to reimagine and reengineer the policies and processes that have benefited some students over others.

“As we chart the path to the future, educators, parents, community leaders, and elected officials must work together to ensure every student and every educator can learn and work in spaces that are safe, supportive, enriching, and equitable,” says NEA President Becky Pringle.

Building community

The schools that have navigated the pandemic with more success had strong relationships with students in place before the pandemic. These relationships will form the building blocks for improved academics moving forward.

“So much of our work is trying to build bridges between students and their teachers,” says Ashleigh Poirier, community schools coordinator at Hot Springs High School in Truth or Consequences, N.M. “We accomplish this by focusing on relationships with families and students while assessing the barriers that have prevented them from being active and engaged. We use a lot of positive reinforcement and trust-building … when working with families who may feel like they are to blame for their children’s difficulties in school, or [with] students who feel overwhelmed because they are so far behind.”

The school also provides tutoring, mentoring, and counseling to students who need extra support.

Schools should also ensure that trauma-informed practices are integrated into the curriculum to support students during class time.

Creating a road map for recovery

When all students finally return to the classroom, educators will need time to focus on learning recovery and social and emotional needs. That’s why NEA is advocating for a suspension of non-diagnostic, state-mandated tests for 2021 – 2022. In the longer term, NEA recommends the following strategies to support learning recovery:

- Differentiating lessons for different learning needs.

- Ensuring adequate intensity when making decisions about extending the school day or year—including after-school activities and reduced class sizes. Sufficient, highly credentialed staff will also be required.

- Using the right assessments. Many standardized tests reward skills that closely correlate with a student’s socioeconomic background.

- Creating an equity plan with stated goals and objectives to allow for equitable learning opportunities for underserved students.

—Cindy Long

3. Extracurricular Activities

How do you stage Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet when local regulations require your teenage lovers to stand at least 6 feet apart? At Westwood High School in the Boston suburbs, longtime theater teacher Jim Howard found a solution: His cast first rehearsed for months outside, then recorded their lines. Those audio tracks were merged with images from a graphic-novel version of the play to create an animated film.

After 25 years as an educator, Howard knows that the work done during rehearsals—the deep dives into scripts, the conversations around a playwright’s intent and tone—matter more to student learning than performances. This fall’s approach preserved that value, while providing a pandemic-safe performance for community members.

Across the nation, arts educators have been similarly challenged. How do you preserve what’s important in arts education—the creativity, the social-emotional learning, the fuel for what Sir Ken Robinson famously called “the power of the imaginative mind”—while navigating virtual learning or physical distancing?

With a dash of creativity and a dollop of technology, it seems.

The Power of Technology

Inside Christine Doherty’s Franklin, Massachusetts, art room, her usual groupings of desks, where students collaborate and inspire each other, have been split up and spaced six feet apart. It could be a grim tableau — think “American Gothic” but with more physical distancing.

But Doherty has found a way to bridge the gap with technology. Last spring, when schools first physically closed, she began recording instructional YouTube videos for at-home students. Now, she’s got both virtual and in-school students—at the same time—and the videos are still helpful. Whether they’re sitting at their kitchen table or classroom desk, every student has an excellent view of her skills demonstrations.

Doherty, who typically creates the instructional videos on her own time, at night and on weekends. (She uses her daily half-hour of planning time to clean and prepare her classroom for in-person instruction.)

“But it’ll help me in the long run because hopefully I’ll be using them for years.”

Doherty uses Screencastify to record the videos, and this year switched to Google Meet, her district’s preferred platform, to share them with students and also with her elementary art colleagues across the district.

“The pandemic has enabled so much more collaboration than before,” she says. “I’ve seen techniques done in new ways, skills taught in ways I never would have thought to teach them. This is an opportunity to see how each other teaches!”

Getting the Band Back Together…

Meanwhile, instrumental music and chorale teachers are working hard to make sure 2020 isn’t the year the music died.

At Charleston High School in Illinois, choir director Juliane Sharp has moved her classes into the auditorium, so that masked students can sing 10-12 feet apart. Band director John Wengerski also has divided his ensemble, and is using “instrument sacks” to contain respiration.

“These are the things [students] need to do to keep being able to do what they love,” Sharp told a local newspaper.

Still, music educators have had to sacrifice much of what they love this year. “Last year we started our very first orchestra, and I got so many violins, in so many sizes, for second- through fifth-graders” says Colorado elementary music teacher Yolanda Calderón. “This year, I doubled our inventory — and not a single instrument has been touched. It’s so sad!”

To limit contact between groups of students in her school’s hallways, Calderón and her arts colleagues have closed their classrooms. Instead of students coming to them, they’re rolling carts of supplies to grade-level classrooms. “I’m taking this dog-and-pony show on the road!” she says. This means Calderón has had to set aside her ukuleles and xylophones—how could she wheel 30 ukeleles through the hallways?

For safety reasons, she’s also silenced the perennial project of fourth-grade students: the recorder. (Many parents may not grieve this particular development…) “Oh no, we cannot,” she says. “They’re blowing into it! It’s basically a COVID projector!”

As an alternative, Calderón is relying more on smaller, percussive Orff instruments, like drums, triangles, finger cymbals, even Tupperwares for her at-home students, and also turning her attention to online resources, like Chrome music lab and QuaverMusic, which her students can use to compose music, mix audio tracks, and more.

“This week my fourth and fifth graders were low-key Foley artists!” she says. (A Foley artist is the person who adds everyday sound effects to movies, like clocks ticking or cars backfiring.) In this project, Calderón’s students worked with a library of mini-sounds, like ocean waves, to mix together three audio tracks for short videos. “We talked about balance, which is a very fundamental musical concept,” she notes.

The pandemic will end eventually, but many of these new resources will persist, educators say.

“I think, like any seasoned teacher, I’m going to recognize that everything I take from this year will go into my bag of tricks and I’ll pull it out as I need it,” says Howard. “As much as we want to put this experience behind us, I don’t think forgetting this year would be valuable.”

—Mary Ellen Flannery

4. Privatization

“Legislation to unmake public education is being rolled out across the U.S.,” says University of Massachusetts Lowell professor and education historian Jack Schneider.

Conservative legislators in at least 15 states are aggressively pushing voucher expansion bills that divert money from public education to private schools. Rooted firmly in racism, these schemes could so profoundly degrade and re-segregate schools that if they pass as written, public schools might “never look the same,” says Schneider.

We’ve seen it before: Privatizers swoop in and attempt to grab money from public schools during times of crisis. They peddle silver bullet solutions—such as virtual learning, privately managed charter schools, or vouchers schemes—that don’t address students’ needs and drain resources from the public schools that 90 percent of families rely on.

The downsides of these privatization plans are numerous, including drops in student achievement, huge class sizes, poorly paid teachers, and rampant scandals over finances and lack of transparency.

The pandemic has led to an uptick in these efforts. “They pitch these offerings as stepping up to help out the country in a moment of crisis,” says Gordon Lafer, a political economist from Eugene, Ore. “But it’s terrible for education, partly because so much of education depends on the personal relationship between teachers and students.”

Corporate interests also use crises to convince school boards to outsource jobs held by ESPs, often targeting transportation as well as custodial and food services.

“Privatizers function in a world without transparency and public accountability, two things we must have when health and lives are dependent on the operation,” says Tim Barchak, a senior policy analyst at NEA. “There were countless examples of ESPs putting their own health on the line for students during COVID. How do you ask that kind of commitment out of a contract employee with no ties to the community?”

Unions have decades of experience working with community allies to stand up to privatizers. In the wake of COVID-19, fighting them off will occupy public education advocates for years to come.

—Amanda Litvinov

Learn More

Find out more about vouchers, and how to fight them.

Find out how to fight privatization in a time of crisis in this webinar from NEA’s ESP Quality department:

5. Equity and Fairness

Have you ever found yourself listening carefully to what someone is saying while ignoring the background noise in the room? It’s only when someone points out the other sound that you realize it’s even there.

This is called selective attention. It allows us to focus on what matters most to us and block out the problems around us. But once you notice the problem, you can no longer ignore it.

For years, certain elected leaders have deprived schools in communities of color and rural districts of vital resources. Now, the pandemic has shined a glaring spotlight on the results of those deliberate policy choices, which have created inadequate school funding, inequities in access to technology and broadband, and food insecurity. The rest of the nation has finally seen what educators have known for a long time. And they cannot unsee it.

Rewriting the rules

Now that more people are paying attention, educators are amplifying their work to help right these wrongs, so every school has engaging materials and up-to-date approaches, healthy meals, and emotional supports to set kids up to succeed.

Take Montgomery County, Maryland, where educators have increased access to rigorous classes and club activities for students of color through an initiative called the “Minority Scholars Program.” What started out in one high school 15 years ago has now spread to 25 high schools and 22 middle schools, engaging 2,000-plus students.

And in a Chicago suburb, union members are partnering with parents, providing the tools and resources caregivers need to advocate for their children. Among other resources, the local union offers racial justice trainings and workshops on how trauma impacts student learning.

Getting loud and proud

Across the country, educators and their unions are pushing harder than ever before. They’re demanding that those in power provide adequate resources to reopen school buildings safely and ensure that students no longer go without.

Over the last year, we’ve seen the power of this collective activism. Nationwide, educators delivered meals and learning packets to students, and bus drivers set up mobile hotspots for students who didn’t have internet access.

And when discussions around reopening school buildings took center stage, educators made sure they were involved. In Iowa, for example, leaders and members of the Des Moines Education Association immediately connected with administrators and school board officials to prioritize student learning and educator safety. They organized members to join every district committee, so their voices and concerns were addressed up front.

Moving forward together

When NEA President Becky Pringle was elected in August, she laid out her vision for the organization: “I am leading a movement to reclaim public education as a common good, as the foundation of this democracy, and then to transform it into something it was never designed to be—and that is a racially and socially just and equitable system that prepares every student to succeed in a diverse and interdependent world.”

She added, “I cannot do this alone. It is only together that we can ensure every student lives into their brilliance.”

—Brenda Álvarez

6. School Funding

The pandemic has taken a steep toll on state and local budgets, resulting in a staggering number of job losses in public education—and it could get worse.

Together, public K–12 schools and higher education institutions lost more than 1 million employees in 2020, including some 670,000 K–12 jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Among them are nearly 200,000 ESP positions across K–12 and higher education institutions, reports the U.S Census Bureau. In total, that’s nearly three times the number of education jobs lost during the entire Great Recession of 2008 – 2013.

In the end, students pay the price, facing larger class sizes and the erosion of the rich curriculum and services they deserve.

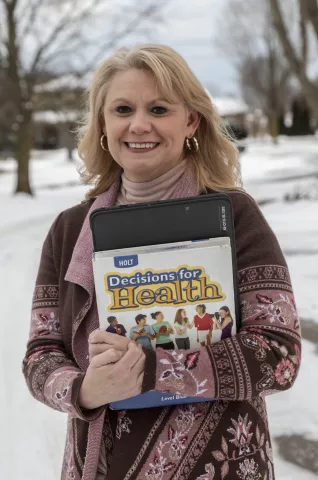

As an “electives” teacher of health, physical education, and nutrition at Romeo Middle School in Michigan, Sarah Bigelow always has some level of concern that her position could be cut when the economy hits a bad patch. But she was on high alert last summer when lawmakers said school budgets might be cut by up to 25 percent.

For students to lose their electives would be “devastating,” Bigelow says. “For some students that’s the best part of their day, where they excel.”

And for her own family—her husband and daughter, who has special needs—a layoff would be disastrous. “For us to lose half our income—we would not be able to continue to pay our bills,” says Bigelow, who has been a teacher for 18 years.

Fortunately, drops in state revenues were not quite as bad as predicted. Districts have moved money around, many states have dipped into rainy day funds, and federal COVID-19 relief packages have helped.

Bigelow still has her job—for now. But the economic toll of the pandemic will continue to be felt for years to come.

Making waves in Washington, D.C.

Educator activism is already making a difference. At the federal level, educators helped bring massive change to our nation’s capital by electing a new president. From day one, the Biden-Harris administration has listened to educators about what schools need to operate safely and how to serve students more equitably.

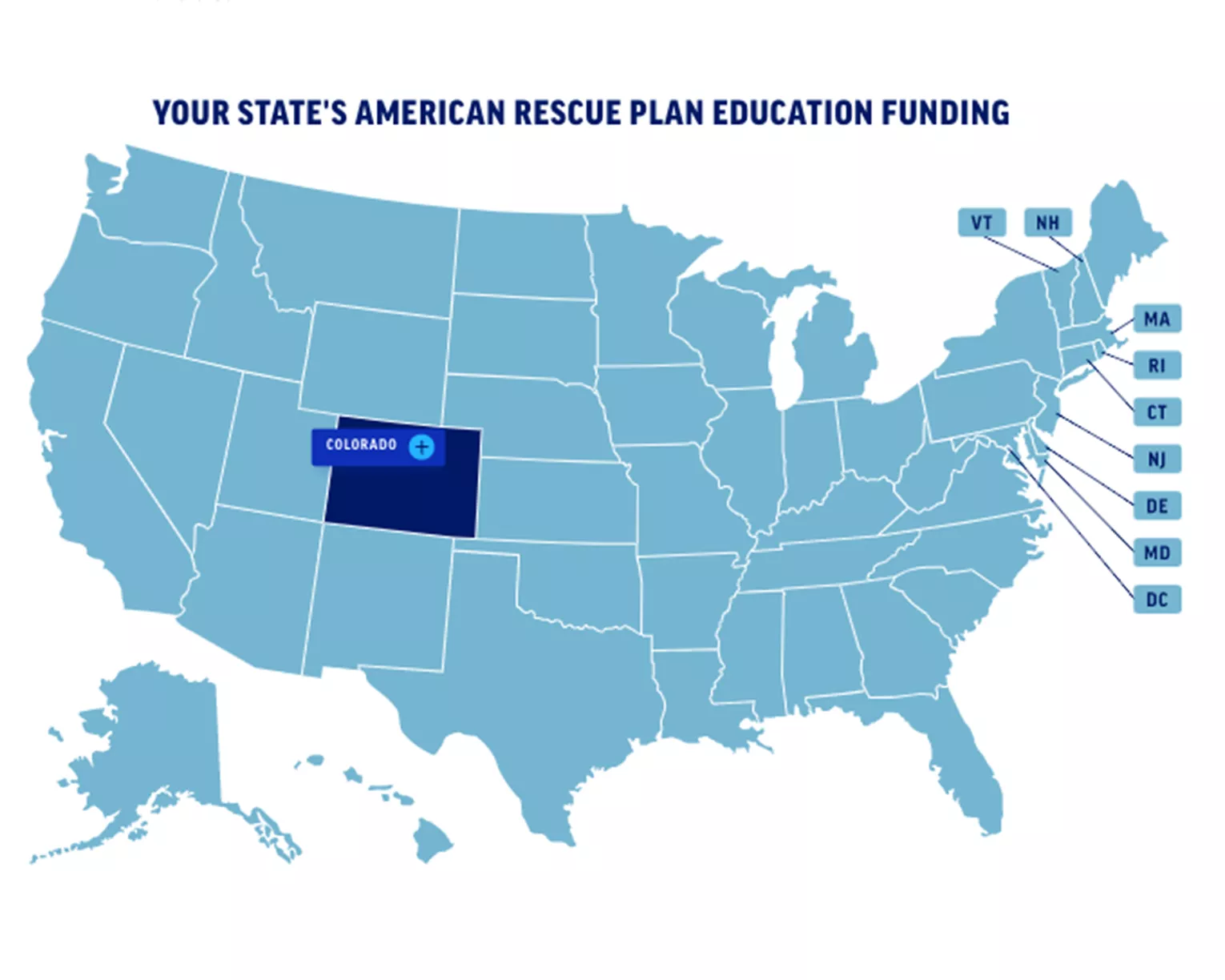

Educators clamored for Congress to pass coronavirus relief bills that have provided critical funds to address schools' immediate needs. In March, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan, which will bolster schools in the long term with an additional $170 billion for education. That funding will create and protect millions of education jobs, cut child poverty in half, and make health care more affordable.

Still, in the coming years it will take a chorus of educator voices in statehouses and school board meetings across the country to push back against education cuts proposed by policymakers who don’t know (or don’t care) what our students need to succeed.

—Amanda Litvinov

Learn More: The American Rescue Plan

7. Mental Health

How many challenges did California teacher Jesse Holmes face this fall?

Three weeks into the school year, she was reassigned from first grade to fourth, a grade she never previously taught. Not long after, her district switched from all-virtual to a hybrid model that has teachers simultaneously juggling at-home and in-person students—except when schools are closed altogether for wildfire evacuations, which also happened.

Five-minute activities now take 30. Login issues happen all the time. When lessons don’t get covered during the school day, Holmes feels obligated to create 30-minute instructional videos at night, at home, so that nobody falls behind.

Toss in a new learning management system, her role as local union rep, and oversight of the online schooling for her own three kids, ages 1 to 7—and, oh yes, a global pandemic that has killed more than 400,000 Americans.

“By November, I just wanted to be happy and I wasn’t. I wasn’t eating and I definitely wasn’t sleeping more than three hours a night,” recalls Holmes.

Even in the best of times, the life of an educator is hard on a person’s mental health. “Educators have a natural drive to care for other people, and we’re left with whatever’s left,” notes Jessica Walsh, a Delaware teacher who trains her colleagues on self-care practices.

Last year, a pre-pandemic study by English researchers found that an increasing number of teachers face mental-health issues, and that “sleeping problems, panic attacks, and anxiety issues” had contributed to teachers’ decision to leave the profession.

Now, the trauma of living through a pandemic, as well as ongoing racial and economic inequities, has deepened those issues, says Sunni Lutton, a University of Florida counselor.

Holmes reached her breaking point early this year. With her health in the balance, she forced herself to start saying no, put down her phone on weekends, and set limits on the time she spends “at work.”

Similarly, across the country, educators and their unions are developing much-needed practices and resources for mental health. Many will last long beyond the pandemic—some ingrained in personal habits, others codified into employee contracts.

‘Shifting Your Mindset’

Peggy Hoy is an instructional coach and union leader from Twin Falls, Idaho, who began training her colleagues on resiliency a few years ago. “Even before the pandemic, it was like, every year, more and more things get added to teachers’ plates. We’re really good at taking things on, and really bad at letting them go,” she says.

To be the best teachers for their students, teachers first need to figure out how to take care of themselves, she says. It’s like when flight attendants tell you to put on your own emergency air mask before assisting others. “If you can’t take care of yourself, you can’t take care of the people who rely on you,” says Hoy.

This can be a difficult lesson for educators, notes Walsh, a Delaware kindergarten teacher who also does self-care trainings for colleagues. “It’s a caring profession. Through my work in education and the education associations, I spend a lot of time caring for students, whether it’s in my classroom or advocating on a larger level. I know I’m not alone in that,” she says.

But educators can't just live with the consequences. “We can’t affect our stressors, but we can change our reaction to them,” says Walsh. “It’s about shifting your mindset and the habits you incorporate daily. It’s how you live your life. Then, when the stressors come, you can manage them.”

The consequences for stressed-out educators (and their students) are dire. Toxic stress can affect every system in your body—respiratory, cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, nervous and reproductive—as well as your ability to listen and process information. In the short term, acute stress has been shown to trigger such things as asthma, headaches, or vomiting; in the long term, it can cause chronic fatigue, depression, metabolic disorders like obesity and diabetes, hypertension and cardiac disease.

Across the country, educators and their unions are developing much-needed practices and resources for mental health. Many will last long beyond the pandemic—some ingrained in personal habits, others codified into employee contracts.

Research also shows regular mindfulness practices around breathing, journaling, and more can help, although many people will need more sustained care from mental-health providers to manage their mental health.

“People really need to work on their foundations, to find out how and why they react to trauma the way they do” says Lutton. “We want a 1-2-3 solution, but it’s not. Because of the layers of trauma that saturate our society, we really need to dig deep.”

Bargaining for Educator Health

Recently, more “self-care” or mindfulness trainings have been provided to educators by their unions, like in Idaho and Delaware, but educators also have found support in contracts negotiated at the bargaining table. In Phoenix, where students and teachers have been working from home, but education support professionals in school buildings, the Phoenix Union Classified Employees Association (PUCEA) recently negotiated shift rotations for all ESPs, regardless of job category.

The union also pushed the district to hire more health and wellness coordinators, specifically for staff. “Instead of going through the Employee Assistance Program (EAP), where you have to go through the whole approval process and then only get six sessions, you’ll have somebody in-house who will just be a phone call away. You can say, ‘hey I’m having a hard time. Can you give me some strategies now to get through the day?’” says PUCEA President Vanessa Jimenez.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the union was making slow progress on these issues, says Jimenez. The new attention to staff’s health is one good thing to come out of the pandemic, she says.

In Idaho, Hoy’s union bargained for release time that provides educators with an opportunity to do their work—away from students—and a system that rewards educators with days off when they substitute for absent teachers. Both help to manage stress and workload. Additionally, sick leave policies now allow for mental-health days.

This is about doing what’s best for educators’ health, but also what’s best for student learning, says Hoy. “I really, really think to be 100 percent present for your students, you have to be 100 percent present for yourself,” she says.

For Holmes, her contract is a reminder that she is paid to work 6.5 hours a day, five days a week. Since the fall, she has set some personal limits on her use of technology outside the work day. “I have had to learn to tell myself no. And it’s really hard,” says Holmes.

But, she says, it’s also really healthy.

—Mary Ellen Flannery

8. Technology

If a year of remote learning has proven anything, it’s that there is no substitute for face-to-face, in-person relationships among students, teachers, and other school staff. But many districts have now invested millions of dollars in distance learning infrastructure, and that means technology is likely to play a more prominent role in education, even when everyone returns to the classroom.

That might be OK for many educators who will emerge from the COVID-19 crisis with new skills and a greater level of comfort with technology.

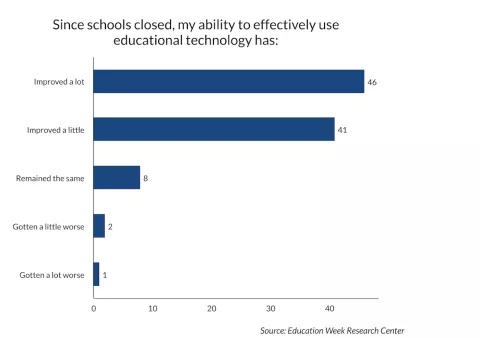

According to a December 2020 survey of teachers by Education Week, 87 percent of respondents reported that their ability to use technology improved by “a lot” or “a little” during the pandemic.

“I feel like the system is generally thought of as stagnant and unable to adapt. [This past year] has shown otherwise,” says Maurice Telesford, a high school science teacher in Lansing, Mich. “Before COVID[-19], some teachers had already flipped their classrooms or were using Google Classroom, etc., but now everyone knows how to do it, and that’s great.”

Still, the integration of digital technology into instruction and practice will always require access to relevant, high-quality, interactive professional development for every educator. As NEA makes clear in its digital equity statement, technology is a tool to enhance and enrich instruction for students and should not be used as a way to replace any educator or limit that person’s role.

Ultimately, the conversation around the use of education technology should continue to focus on one overriding concern, Telesford says. “Is it the best tool in that moment? Will it help solve the problem that’s in front of us? That’s what we have to always figure out.”

—Tim Walker

Learn More

NEA offers multiple micro-credentials intended to teach educators how to leverage digital tools and to support your students using critical thinking, communication and collaboration skills. Micro-credentials are free to NEA members.

9. Solidarity

Since the pandemic began, educators have continually put pressure on their school districts to provide guidance, flexibility, and support. They’ve done this during a time of deep social isolation and loneliness, and many turned to their unions for camaraderie, courage, and community.

Esmeralda Maldonado, a paraprofessional for students with special needs for the Isaac Elementary School District, in Phoenix, Ariz., is one such member. When school buildings closed last spring, she quickly shifted gears to help cafeteria workers prepare more than 200 meals a day for students—and that’s when she noticed something was amiss: no masks, only gloves; and the time-and-a-half pay that was promised was missing.

A phone call between Maldonado and union representatives quickly snowballed into a winning campaign. Maldonado, along with food service manager Nancy Arvizo, organized a group of typically reserved cafeteria workers to act. They sent letters and met with the superintendent to demand more support from district officials.

While the masks never arrived (they found or made their own), the district did pay time and a half to cafeteria staff and every education support professional who worked when school buildings were closed.

Meanwhile, Grace Hopkins, a second-grade dual language teacher in Austin, Texas, battled her district along with thousands of other educators. Among their demands: a delay to in-person learning; “hero pay”; accommodations to work from home for those with underlying conditions; and the flexibility to determine how best to staff classrooms.

The group organized many actions, including a 200-plus car caravan and press conferences, and won many of their demands.

“I think the pandemic really helped people understand the power of ‘us’ through our organizing efforts,” explains Hopkins.

Maldonado agrees: “While the pandemic isolated us, the union brought us together.”

Tom Israel of NEA’s Center for Organizing adds that, “In places all across the country, the pandemic has demonstrated to members the real value of belonging to the union. They see their local and state affiliates stepping up to demand safe and just schools, and they’ve seen that the association can be the best source of information during these difficult times. Going forward, the clear lesson is that when NEA affiliates lead on fighting for the issues members care about, educators will join and get involved.”

—Brenda Álvarez

10. Safer Schools

No one knows exactly how COVID-19 will impact public health in the months to come. So everyone will have to remain vigilant, particularly in our nation’s schools. While basic practices—such as mask-wearing, frequent handwashing, and sanitizing—are effective, they also cost money. After decades of underfunding schools, lawmakers will face more urgent pressure to invest in the health and safety of our students.

Placing a nurse in every school

School nurses have never been more essential to a healthy school environment. Their duties go far beyond scrapes and bruises. They manage medications, assist students with disabilities, act as liaisons between public health departments and school staff and families, promote health education, and provide mental health services, among other responsibilities. Now they also screen for COVID-19, conduct contact tracing, and manage isolation rooms for potentially infected students.

“The pandemic trajectory confirms we need school nurses more than ever. Students need much more mental health support in coping with academic, personal, and family challenges resulting from COVID-19,” says Cynthia Samuel, the nurse at Grove Street Elementary School in Irvington, N.J. “School nurses are positioned to render support as well as resources … to address the pandemic-related disparities encountered by Black, brown, and Indigenous communities.”

Clearing the air

School infrastructure plays an equally important role in keeping students and staff safe. “Appropriate ventilation has always been important in schools, but it’s also crucial to fight COVID-19,” says Joel Solomon, a senior policy analyst at NEA who leads the organization’s health and safety team.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office says that to prevent the spread of the coronavirus inside schools, more than 41 percent of school districts need to update or replace their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems in at least half of their buildings.

Students in these older buildings often contend with mold, leaky ceilings, and frequent colds and flu, says Jean Fay, a member of the Massachusetts Teachers Association Environmental Health and Safety Committee. She adds that they also experience increased asthma rates from poor air circulation and lethargy from high levels of carbon dioxide. “It took a pandemic to point out that air quality is critical for the health of those who occupy a building,” Fay says.

—Cindy Long

Learn More

We’ve designed both a comprehensive document and a short guide to assist local leaders, staff, and members to create an indoor air quality plan as part of an overall COVID-19 mitigation strategy.

Get more from