Many young educators join the union for the insurance, but soon find themselves on the road to self-discovery. They tap into confidence they never knew they had; make friends who inspire and support them; and learn how to raise their voices to make a real, direct impact on students in their communities and across the country.

NEA Today spoke with four NEA-Retired educators who shared their stories of personal and professional transformation.

Power in the district, standing in community

Felecia Hampshire

Green Cove Springs, Florida

It was 1983, and I was excited—and nervous!—to be interviewing for an office position with a school administrator. My husband and I had three children, and I had dropped out of college because we were struggling. I needed a better job, but the interview did not go well.

“Gal,” he said, “you can’t work here. I can’t hire you in the office. But there’s a custodian position you can have.”

I felt strongly it was a racial issue—discrimination was a known problem in our school district. But I didn’t give up.

I took the custodian position and got involve with the Clay Educational Staff Professionals union. My colleagues there taught me about my rights and opportunities. I also began to see how essential it is to build strong relationships and have the right people in key positions.

I worked for a superintendent candidate who was a member of the local and had progressive ideas about race and gender. We became close friends through the union, and after she won with the union’s support, she helped me get a new position—in the department where I had first applied. That was just one of the many times the union opened doors for me. Since then, I’ve had success in support positions in district schools and have held top leadership positions in the union locally and statewide.

In 2007, the campaign skills I developed through the union helped me become the first Black woman to serve on the Green Cove Springs Town Council. The strategies I learned, the confidence I gained, and the support I received from the union all made that possible.

Later, I put my bargaining and consensus-building skills to use in winning a pay increase for city workers.

Through these successes, I earned the support of city employees. I’ll never forget the sanitation worker who told me: “Felecia, you were really there for us, and we appreciate all you have done.” The police also cooperated with me, because I lobbied federal legislators to secure funds for a much-needed new headquarters.

One of the most important benefits has been the connections I’ve made in the community that I was born in and have grown to love so much.

Twenty years ago, my husband, Clarence, and I decided to celebrate our city by starting a festival that some 7,000 people now attend each year.

A long-running community parade has now become part of the festival. I marched in it when I was five, and just a few years ago, I was the grand marshal.

A sense of Unity

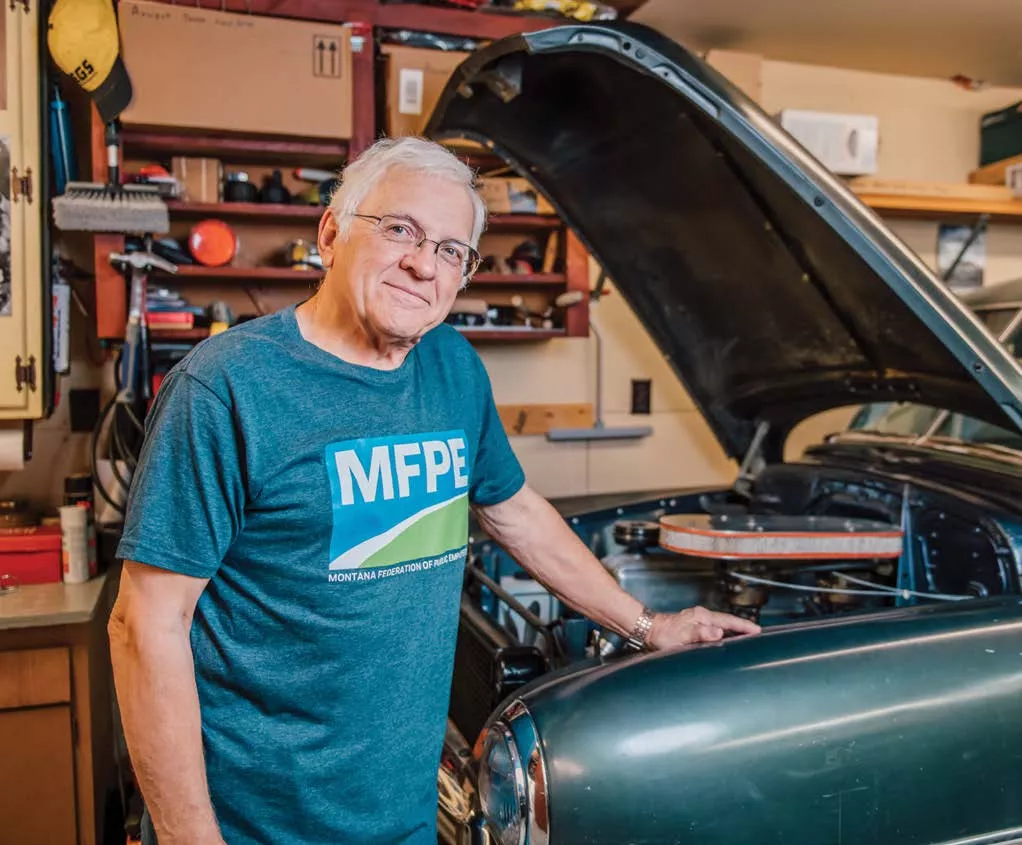

Jerry Rukavina

Great Falls, Montana

For me, one word comes to mind when I think about my years in the union: unity.

I felt it during a strike by the Great Falls Education Association. It was one of the longest local strikes in the nation during the late 1980s, with 820 teachers walking out for nearly a month. It was very hard on members.

As an executive committee member at the time, I worked with a local credit union to secure $1,000 loans for union members who were on strike. I was an automatic mechanics teacher, so I fixed cars in driveways to make ends meet. Members helped each other in a host of ways, even financially.

I remember that I disagreed with another leader in the union on nearly every political issue, but she was highly supportive during that strike. I vividly remember protesting alongside her when unauthorized workers from other states filled our jobs.

We all wanted to protect our rights, but we mostly valued the work we did together. That unity grew from the idea that we guided 11,000 kids from childhood to adulthood successfully. We all wanted that.

I have also seen that sense of unity more personally. When I became a field consultant for local unions in 1995, I worked with a young man who was struggling as a teacher. Several of us in the union encouraged him to keep trying and offered support.

Several years later, the teacher had received better training and help, and he was succeeding. He became a happier, better teacher, and our schools gained a valuable asset. Working together paid off in the best way.

I began my labor experience with the machinists union even before I became a teacher. I was an instructor for apprentices and then began to teach auto mechanic trade skills at our local high school. I loved teaching and served 21 years as an educator and leader in the union.

I hope others like me find the value of the union in practical ways, but also understand how the word itself conveys what really counts: unity in our profession and unity in our union.

Impacting local education policy

Jane Franz

Newton, Massachusetts

My husband teases me about my odd habit of watching school committee meetings on TV, no matter how long and tedious. I suppose I should have had my fill after teaching for 35 years. But through activism with my local as well as the Massachusetts Teachers Association and NEA, I have come to appreciate how important school policy is. And the union has given me a wonderful opportunity to have a voice in the future of our suburban Boston schools.

As an executive board member with the Newton Teachers Association, I have interviewed dozens of political candidates over the years, talking with them about education issues and bringing information and recommendations back to my union colleagues. Now when I walk around town, candidates stop me on the sidewalk and say, “Jane, so nice to see you. We’ll have to get coffee.”

I develop a relationship with them. Then, if the candidates get elected, they often seek my opinion.

I appreciate how the union has paved the way for me to do this meaningful work, but these efforts are really for the benefit of my students. They have always been a magnetic pull for me. I still love being a part of a school and seeing students grow and learn.

When I turned 60, I was ready to retire, but I was asked to stay on to teach English language learners. Now, at 73, I’m still doing it, teaching math in middle school three days a week. My students make small gains each day, but seeing the extent of their academic needs reminds me of the importance of local school policy.

So when I watch those school committee meetings so closely, it’s because I have the pleasure of seeing my ideas and the union’s position come to the floor an hopefully come to fruition.

Finding her voice

Lisa Fricke

Omaha, Nebraska

I remember when I first felt the power of our united voice. I was at a Nebraska State Education Association (NSEA) government relations training in 1976. I was a fairly new teacher and union member, and the words of a trainer have stuck in my mind to this day.

Teachers often say they “aren’t political,” he noted, but they need to understand that every education decision that politicians make affects their classrooms.

I took this message to heart. And through trainings like these, I’ve learned that educators need to collaborate on political issues in order to improve public education.

I held several positions over the years where I could influence political activity, including chair of the NSEA Government Relations Committee. I also met with political leaders and testified on critical education issues. This experience launched me into a new role in 1992, when a personal issue became political.

I was frustrated by the penalties my husband and I incurred when we borrowed from our IRA to help pay for our son’s college expenses. I felt others likely faced a similar problem. And for some young people, this law could dash their dreams of going to college

I discussed the issue with NSEA leaders, and they encouraged me to run for election as an at-large delegate to the NEA Representative Assembly. I went for it—and I won! And, in front of about 5,000 delegates, I presented my resolution, which would make it a priority for NEA to advocate for changing this harmful law.

I was scared to death, but with the confidence I had gained from my union work, I apparently made a persuasive argument. The delegation approved the resolution, and with NEA’s lobbying efforts in Washington, in partnership with others, Congress eventually voted to change the law.

I now serve on the Nebraska State Board of Education, working on equity and inclusion, early childhood education, and state standards, among other issues. My understanding of politics has given me the self-assurance to testify at legislative hearings and speak to constituents and legislators. It has allowed me to have a voice where it really matters.