Key Takeaways

- The pandemic has worsened food insecurity among college students, especially those who live off-campus and lost their part-time jobs.

- Hunger has a direct effect on students' ability to learn. Plus, food is a basic right!

- Unfortunately, it's not just students who need the growing number of on-campus food pantries. Graduate assistants, low-paid support employees, and adjunct faculty also need help.

At the University of Maine, the on-campus food pantry will distribute around 70,000 pounds of food this year to hungry students and employees, more than twice as much as last year, and about seven times as much as previous years, says Lisa Morin, coordinator of the university’s Bodwell Center for Service and Volunteerism.

“There is definitely more need,” says Morin. “We have found more people in need, and it’s not people with little need, it’s more people who have a lot of need.”

Blame the pandemic, at least in part. Many university students who worked in restaurants or local shops, or as babysitters, dog walkers, etc., were unemployed this year. Many of their parents also lost their jobs—or lives. And, while Congress’ COVID-19 relief legislation has made it easier for millions of college students to access federal SNAP benefits, commonly known as food stamps, many students aren’t aware of it.

Hunger on campuses is growing, as are NEA members’ responses to it. Today, there are at least 700 food pantries on U.S. college campuses, up from just 88 a decade ago, according to the College and University Food Bank Alliance. Some, like Maine’s Black Bear Exchange, which with the campus’ dining halls to provide tens of thousands of pounds of frozen casseroles and chowders, are massive, longstanding models for what’s possible.

Others, like Lock Haven University’s Haven Cupboard in Pennsylvania or the University of Albany’s Purple Pantry, which both opened in the fall of 2019, are rapidly making strikes.

Everywhere—at institutions big and small, urban and rural—the work of feeding food-insecure students has never felt more necessary, say administrators.

“Faculty are discussing the fact that students tell them they haven’t eaten in 48 hours. Or they discover a student is ridiculously tired and ill, and it’s because they’re under-nutritioned,” says Morin. “If somebody calls me and tells me they have a need, I will stop whatever I’m doing and bring them a bag of food. Even if the pantry is closed, I have a key!”

The Consequences of Hunger

In 2018, Temple University’s Hope Center for College, Community and Justice surveyed 86,000 students at 123 two-year and four-colleges: 45 percent said they had limited or uncertain access to food in the previous 30 days.

More than one out of three said they cut the size of meals or skipped meals because they didn’t have enough food or money. Nearly one in five said they had lost weight because they couldn’t afford to eat. About one in 10 said they had gone at least a day without eating for the same reason.

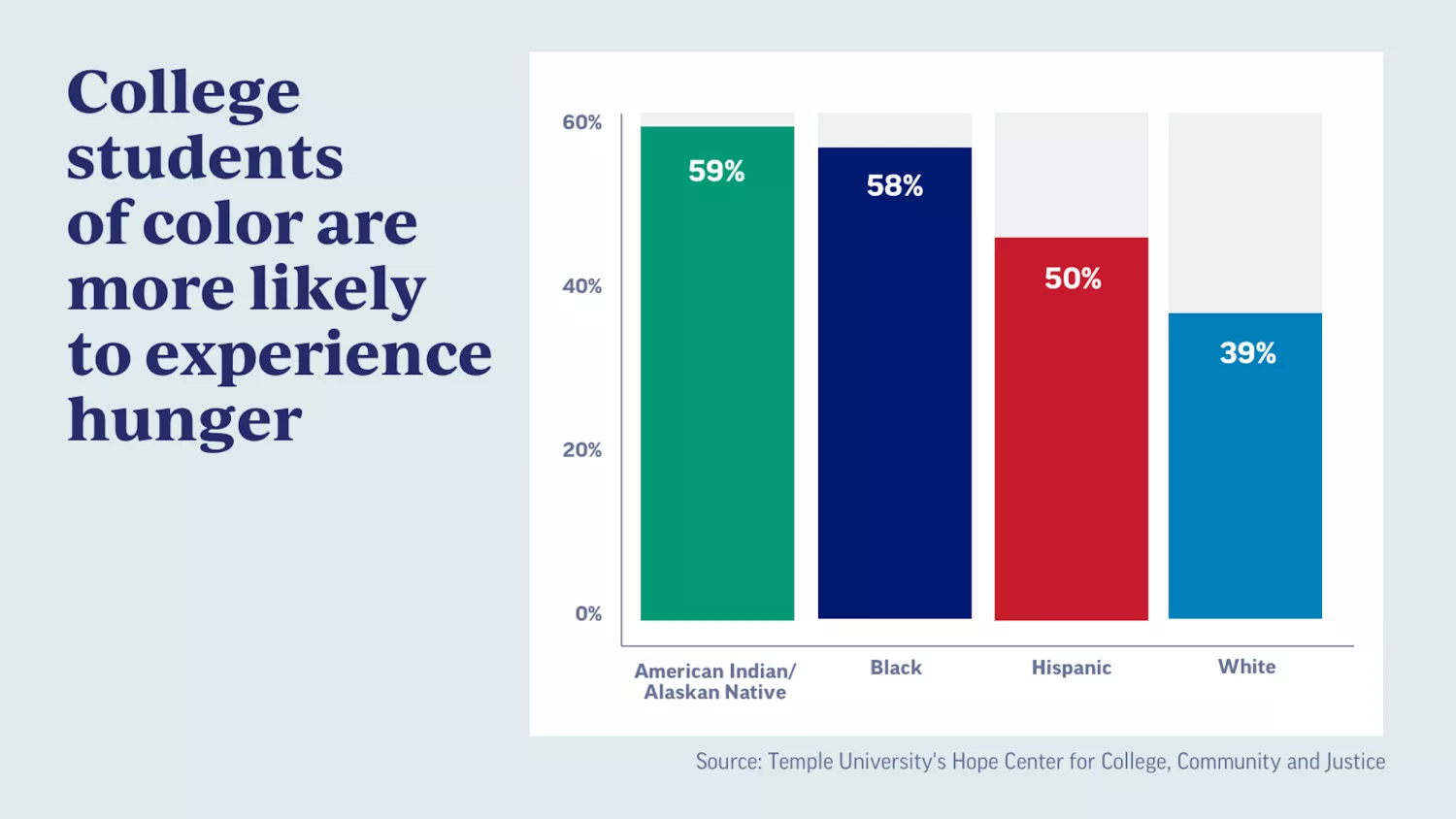

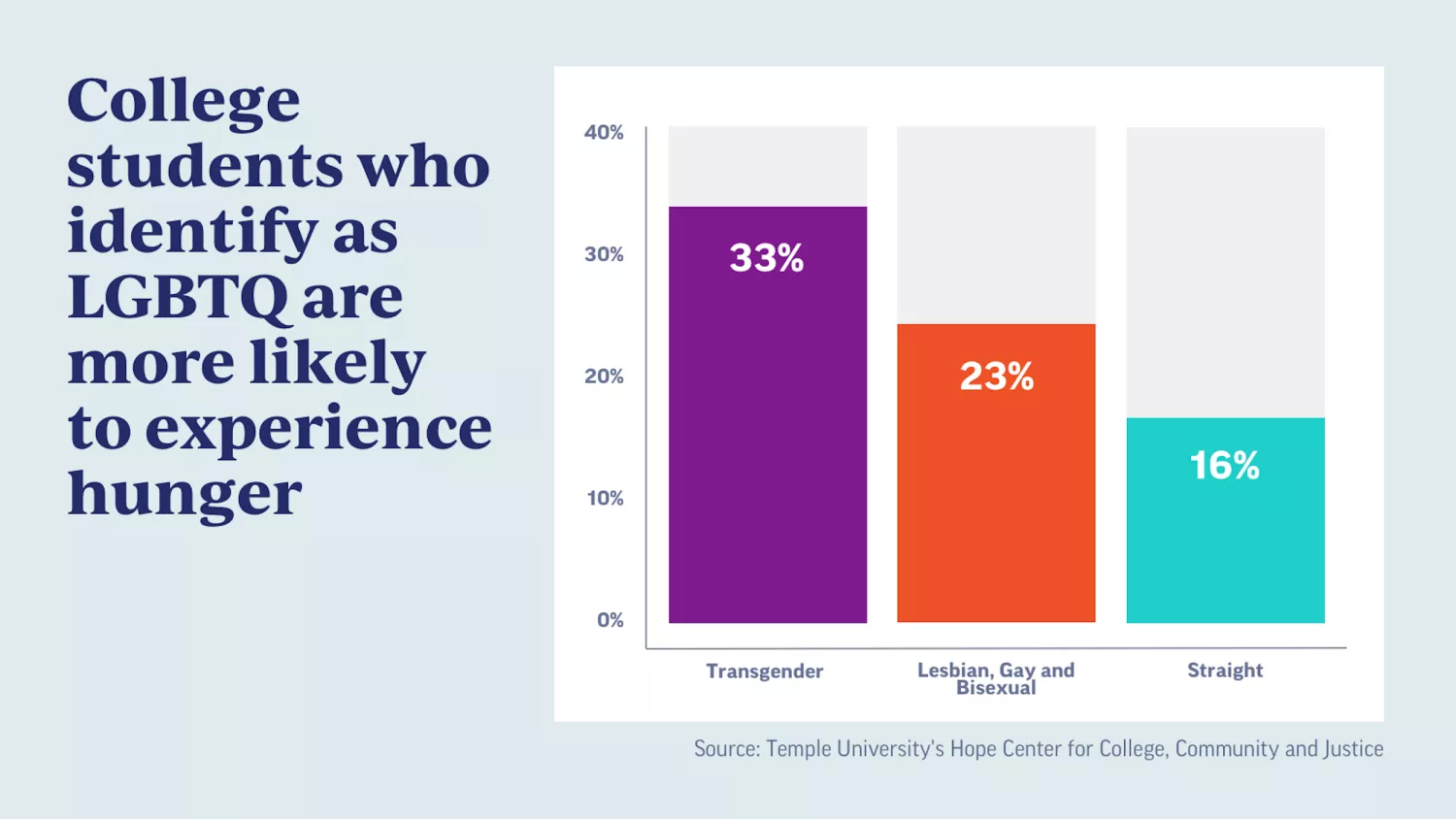

And, even though every student should have enough food to eat, the study showed unequal access to food, depending on race and sexual orientation. Specifically, the rate of food insecurity was 59 percent among American Indian or Alaskan Native college students; 58 percent among Black students; 50 percent among Hispanic students; and 39 percent among White students. Rates also were higher among LGBT students: 33 percent among trans students and 23 percent among lesbian, gay or bisexual students, compared to 16 percent among straight students.

Common sense says hunger affects learning. And, in fact, students who don’t report food insecurity are more likely to get A’s and B’s; students who do report food insecurity are more likely to report Cs and D’s or F’s, the survey found.

For these students, cheap packages of ramen aren’t enough. (Unless you also toss in some fresh veggies, a can of chicken, and a recipe for pulling it together!) “We’re really hammering home the USDA questions—it’s not about when you last ate, but what you ate,” says Morin. “We’re trying to make people understand that good-quality food is important to brain health.”

She recalls an issue with football players who were struggling with food insecurity. “Talk about people who need calories! These may be the first people in their families to go to school, and they’re using school to not only improve their lives but their families’ lives,” she says. “They’re scrounging for calories, and it breaks your heart.”

Who are the Hungry?

At Lock Haven University, a public university of about 3,000 students in central Pennsylvania, students who work at the university’s Center for Excellence and Inclusion came to assistant director Amy Downes in 2019 to talk about hunger. “Several of the students who work for me have struggled, so it comes from a personal place for them. They wanted to help other people. Our motto is that everything we do, we do with love,” she recalls.

Their original idea—to plant a community garden—morphed into starting a food pantry, which they could get up and running more quickly. It opened in October 2019; months later, COVID-19 arrived. And yet, hungry students didn’t stop coming. In its first year of operations, which occurred mostly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Haven Cupboard served more 500 students, or about one in six LHU students, says Downes.

“We’re a family here, and family means taking care of each other,” says Downes.

Meanwhile, at the University of Albany, where more than a third of 1,800 surveyed students say they were skipping meals to stretch their food budgets, the new Purple Pantry provided 50,000 meals in its first year—also during the pandemic.

Most of the students who need help with food are those who live off-campus, administrators note. At UMaine, for example, all on-campus students are required to have a meal plan and all plans provide unlimited meals. Students who rent from private landlords, on the other hand, have to provide their own food. And, for the most part, these students didn’t go home during the pandemic, even when classes were moved online. Bound to rental agreements, they stayed and struggled.

And it’s not just students who need help with food, pantry administrators agree. Graduate assistants, who work as research or teaching assistants, earn an average $18,000 a year, according to the latest NEA report on higher-ed salaries. “And they don’t have the time for additional jobs,” says Morin. “A lot of times they struggle.”

She also sees some of UMaine’s lowest-paid employees from dining halls and custodial staffs.

The Challenges of the Pandemic

During the pandemic, on-campus food pantries rose to the challenge, but wasn’t easy.

At UMaine, Morin is passionate about providing food-insecure students or employees with a typical, stigma-free “shopping” experience. At the Black Bear Exchange, workers play music, provide shopping baskets, and bag groceries that shoppers choose from shelves and freezers. “It doesn’t feel like a handout,” says Morin. Plus, she notes, this age group really wants to make their own dietary choices, whether it’s vegetarian or vegan, lactose- or gluten-avoidant. “It feels like you’re taking something away when you don’t let them choose their food,” she says.

But how do you replicate that experience when the pantry must physically close to visitors? With a week’s notice, Morin created an online ordering system that continues to provide choices around food and time of pickoff.

At Lock Haven, Downes did the same, building an online ordering system that allows her staff to pre-bag orders. “The choice part reduces stigma and shame. It makes it more like any other support service on campus, like tutorial services or counseling,” she says. At pickup, Downes also created a fun, “pick six” table, where students can choose among random items or unusual treats—Cosmic Brownies, microwaveable Beef-a-ronis, apple sauces and granola bars—to add to their bags.

“Going back to semi-normal operations in the fall will be interesting,” notes Downes. With wide availability of vaccines, hopefully most students and faculty will be back on campus, but many still will be suffering the financial fallout of the pandemic, she predicts. “I anticipate our numbers will double, if not triple.”