“The relief is just unbelievable,” says Merrie Wolf, a 67-year-old math teacher in Tulsa, Okla.

This fall, Wolf learned that her $50,000 in federal student debt was gone—forgiven with the click of a button. Goodbye, monthly loan payments! Farewell, sleepless nights.

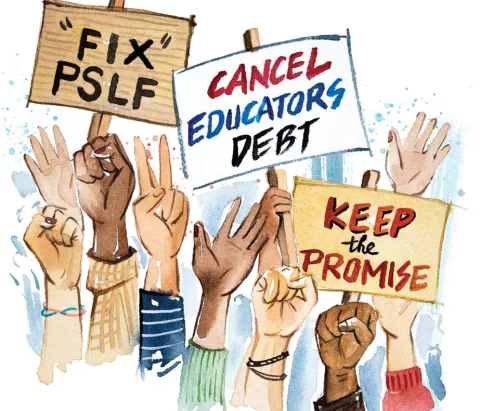

Thanks to years of dogged advocacy by NEA members, federal officials had created a waiver to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program that moved 500,000 borrowers closer to being debt-free. About 22,000 of them, including Wolf, were immediately eligible.

For Wolf, a world without student debt is now a reality. “I can actually sleep!” she says.

Delivering on the promise

All students should be able to pursue their goals through higher education. Whether they aim to be educators or astronauts, what should matter is how hard they work and how big they dream.

But today, as college costs soar and politicians cut programs that are supposed to help, students and families are forced to borrow more and more.

Educators are especially burdened. NEA research shows that nearly half borrowed money to pay for college—and they still owe an average of $58,000 each.

Congress’ solution was PSLF, which promised to cancel the debt of teachers and other public service workers after 10 years. But the program has been like an “American Ninja competition,” a federal official remarked this fall, with 98 percent of applicants getting rejected.

Since 2020, NEA members have written 168,000 emails to the Department of Education (ED) about problems with PSLF.

Your stories made a difference: In October, shortly after Wolf met with Education Secretary Miguel Cardona and other federal officials, Cardona announced a PSLF waiver, broadening the kinds of payments that count toward loan forgiveness.

“You could see the compassion in their faces. I was like, man, these people actually care!” says Wolf of Cardona and his staff. “And it wasn’t just the Department of Ed. NEA was right on top of it!”

It shouldn’t be this hard

What would it be like if Carolyn Hawkins’ student debt was erased?

The 64-year-old Georgia kindergarten teacher might go on a vacation. That’d be a first. Likely, she would start saying yes to family reunions and wedding invitations.

Possibly she’d retire to take care of her 91-year-old mother. It would be nice to have that option.

As it is, Hawkins needs to work to cover her monthly $703 student loan payment, which doesn’t even cover the interest on her six-figure loan balance. “I can’t live in it. I can’t drive it. I can’t wear it. And I can’t eat it. But it’s eating me alive,” she says.

Meanwhile, if Angel Toledano’s student debt were canceled, the California educator wouldn’t be grumbling about the cost of the $11 double cheeseburger deal at McDonald’s that he splits with his wife. And he wouldn’t worry about the $5,000 he spent to secure a conservatorship for his 19-year-old son with disabilities.

Toledano, who teaches culinary skills to youthful offenders in Santa Clara’s juvenile justice system, has been paying back his loans for 15-plus years. And yet today he still owes $60,000—or about $20,000 more than he originally borrowed.

“I trusted them and I got burned,” he says, referring to the loan servicer that the government hired—and fired in 2021—to manage PSLF.

For these educators, a world without student debt is still a dream. “I would feel like a normal person,” Hawkins says.

Make this the new normal

For almost two years, educators have glimpsed a world without student debt. Since March 2020, as part of the government’s COVID-19 relief efforts, ED has suspended compounded interest and payments on their student loans.

But, on February 1, the moratorium ends. “I’m dreading when things go back to quote-unquote normal,” says Toledano.

Wolf used to be among them. For 12 years, she paid up to $355 a month to Navient, a student-loan servicer, only to find out, in 2019, that none of those payments qualified for PSLF. “It was sickening,” she recalls. To get PSLF, she’d have to switch her loans to FedLoan—the only qualifying servicer for PSLF—and persist for another 10 years, working and paying until age 75.

She had resigned herself to that fate until NEA and ED intervened. “I can’t tell you what a blessing it is,” she says.