It’s about 4 p.m. in Room 228 at Skyview High School in Billings, Montana, and resource teacher Deb Roesler is explaining her “action plan.” In the coming days, when she returns to her middle school across town, this white, middle-aged, rural Montanan will invite a student who doesn’t look like her to eat lunch together.

“I’ve been in the biggest groups all day. I’ve never been in a small group,” she says, referring to the “identity groups” that have formed and reformed in Room 228 around age, gender, race, religion, income, education, and more. “But I want to reach out, and I’d like to get to know better the students in the small groups,” she says.

Roesler is among the nearly 200 educators who spend time in Room 228 during the Montana Federation of Public Employees’ annual, two-day Educator Conference. The October event, which hosted more than 3,000 educators, offered more than 500 trainings and workshops—including six from NEA’s Center for Social Justice in the areas of social justice, cultural competency, diversity, and support for LGBTQ students.

These are free workshops, provided upon request, by NEA members—for NEA members. Since 2015, the union’s student-centered, research-based tools have been shared with more than 5,000 educators.

“NEA sends us out to do these trainings because the NEA mission and vision is a great public school for every student,” explains trainer Kevin Teeley, a retired teacher from the Seattle area, to the educators assembling in Room 228. “We want every single student to be achieving and successful in our diverse world.”

With Dreamers marking time, the school-to-prison pipeline thriving, and the divide between rich and poor growing, these may be dark days for educators who care about social justice. But the promise of public education, reminds NEA President Lily Eskelsen García, is “to prepare every blessed child to thrive—and succeed—to love living in a diverse and interdependent world.”

That’s why NEA has dedicated itself to erasing institutional racism, to protecting immigrant families, to standing up for LGBTQ students, and more. “The moral arc of the universe is long, and hearts and minds are bending towards justice. But if our institutions—our policies, our programs and practices—don’t change, then the oppressive conditions that people face will stay the same,” says García.

The educators in Room 228 understand this. Says Montana teacher Richard Montoya: “This is more than a job. We’re inspiring children to walk in their own dreams.”

‘We Should Do This!’

It’s 7 a.m. on the first day of the conference when Teeley and co-trainer Alicia Bata, a high school teacher who works along the North Dakota-Canada border, open the door of Room 228. Fifteen minutes later, the first participant enters. Dozens more follow. At 7:57 a.m., Teeley sends a message to conference organizers: More desks, please!

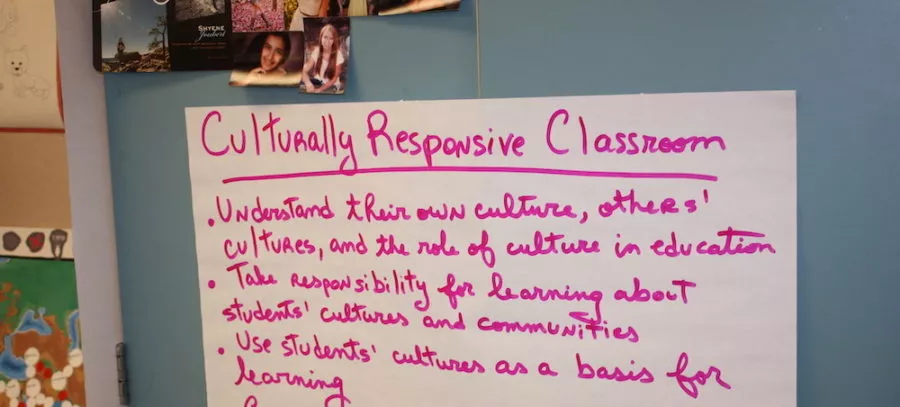

“Am I culturally competent? Perhaps. Do I know everything I need to do? Absolutely not! This is a skill that you need to practice every day,” Bata tells their classroom of 30 educators. “In three hours, we can’t make you culturally competent, but we can make a good beginning… The first step is to learn about yourself.”

Alicia Bata (center) with workshop participants.

Alicia Bata (center) with workshop participants.

Like many places in rural America, Montana lacks racial diversity in its teachers. Ninety six percent are white, according to federal statistics. By comparison, their student population is diverse: 78 percent white, 11 percent American Indian, and 5 percent Hispanic, with small fractions of other racial groups.

“My colleagues have good intentions, but they don’t always have the tools they need [around diversity],” says Billings Education Association officer Theresa Mountains.

It is critical for those teachers to develop “cultural competence,” as NEA calls it, to reach every student, no matter who they are or where they’re from. This depends on educators doing at least four things: valuing diversity, or letting go of the idea that their view of the world is the only one that is normal; being self-aware of their own culture and how it affects their perceptions; understanding how students also are cultural beings; and finally, using what they know to change their classrooms, schools, and districts.

Just by walking into Room 228, these Montana educators are proving they value diversity. Next up is cultural self-awareness. Who are they? At 9 a.m., kindergarten teacher Paige Bealer reads aloud a poem that she has dashed off: “My father’s side is German through and through…my mother is Jewish and Catholic Portuguese. I am of...cabbage rolls, borscht and sauerkraut we stomp ourselves.”

At 10 a.m., Room 228 is talking about culturally competent teaching and curriculum. Allan Audet is a metals manufacturing teacher whose students are working on a life-size, steel and copper, ceremonial Crow headdress, he tells his colleagues. “I just thought, ‘We should do this!’” says Audet, who worked with Billings’ American Indian instructional coach Jacie Jeffers. An hour later, everybody leaves with one idea that they’re willing to implement in their own classrooms.

Kevin Teeley

Kevin Teeley

‘Do It!’

Cultural competency is just one workshop that NEA’s HCR-trained members provide to their colleagues. By lunchtime Bata and Teeley have moved onto social justice, and the educators in Room 228 are taking Post-its and jotting their real-life examples of marginalization, exploitation, cultural imperialism, and other forms of oppression.

There’s the female teacher who was asked by an administrator to attend an IEP meeting for a student—not her student—to be “eye candy” for the student’s father. There’s also the Eurocentric textbooks, the achievement gaps, and more.

“Identify actions at each level—individual, institutional, and societal—to combat these examples of oppression,” says Bata—and they do. For example, the next colleague who casually says, “you don’t look Native” will be challenged, say the educators of Room 28, who also pledge to make it part of their curriculum to celebrate the diversity within Native American groups.

And then it’s onward to “Understanding Diversity,” a two-hour workshop with retired Portland teacher Debra Robinson and California first-grade teacher Laura Ancira. “This is about honoring and understanding our students,” Robinson tells Room 228. It’s followed by two more hours on “Valuing Diversity,” and then an additional four hours with retired Wisconsin teacher Bonnie Augusta and retired Georgia teacher Toni Smith on creating safe spaces for LGBTQ students.

Every time the door opens, educators leave with a written action plan.

“Post it on your fridge, do not forget this. Do it,” urges Bata.

Photos: Mary Ellen Flannery