Key Takeaways

- The intent of Banned Book Week is to celebrate the freedom to read and highlight the value of access to information, even when it's unpopular or unorthodox.

- These days, it's not so much the quantity of book bans that alarm educators, but that they're instigated by politicians seeking to divide parents and educators.

- RAA-recommended author Bill Konigsberg has five books on a Texas lawmaker's list of targets—and he's not backing down. He knows his books are saving the lives of LGBTQ+ kids.

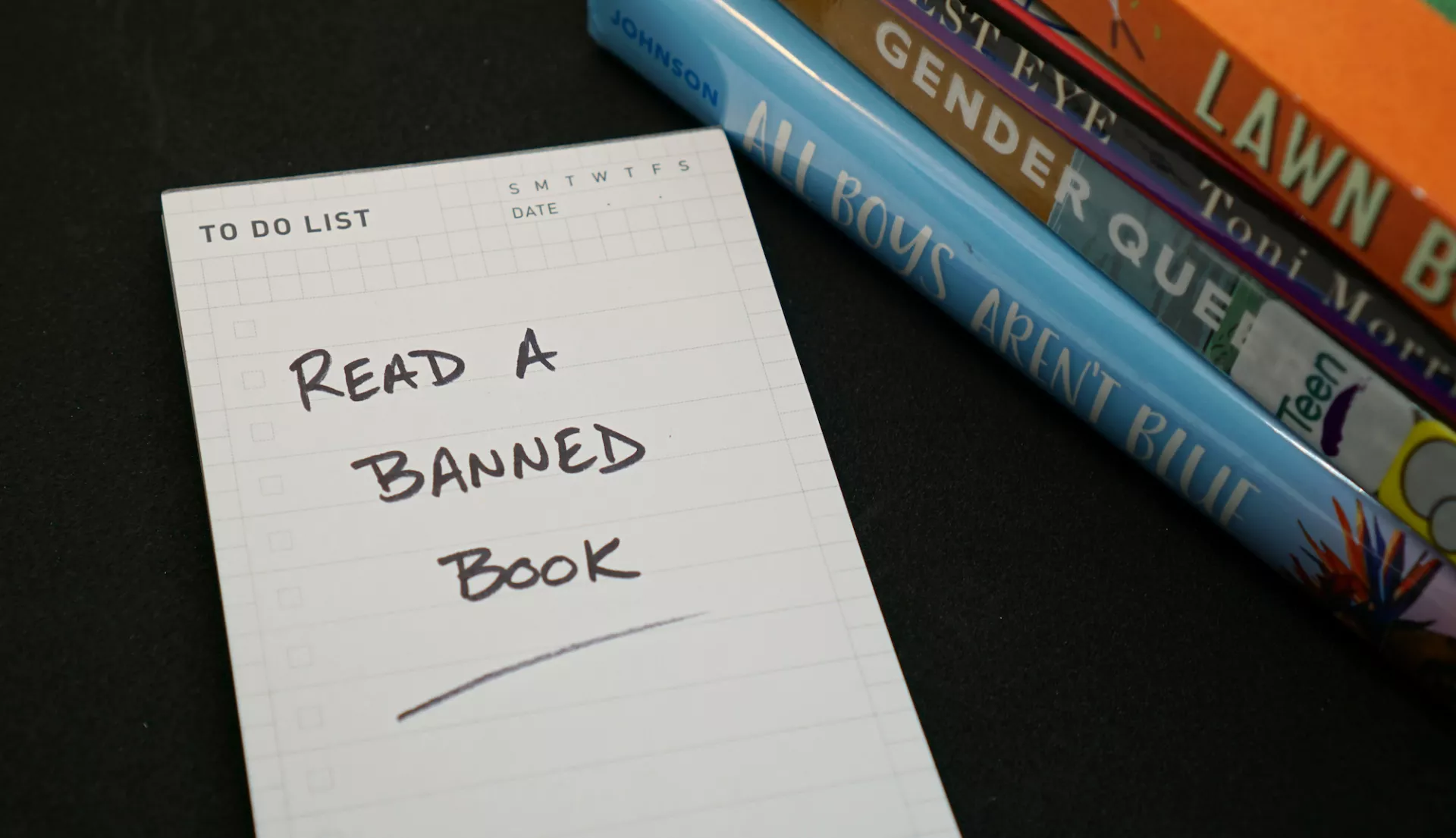

This year’s Banned Book Week, Sept. 18-24, takes place during an unprecedented time of book bans and challenges in U.S. schools.

Between July 2021 and June 2022, more than 2,500 book bans were enacted in 138 districts in 32 states, resulting in the removal of more than 1,600 titles from school libraries and classrooms that serve roughly 4 million students, according to a report released this week by PEN America. And that’s likely an underestimate, as PEN America compiled only the bans reported to them or covered in the media.

The state with the most bans? Texas with 801.

The subject matter most often banned? Four out of 10 banned books had LGBTQ+ characters or themes. Four out of 10 also had protagonists or characters of color, PEN America found.

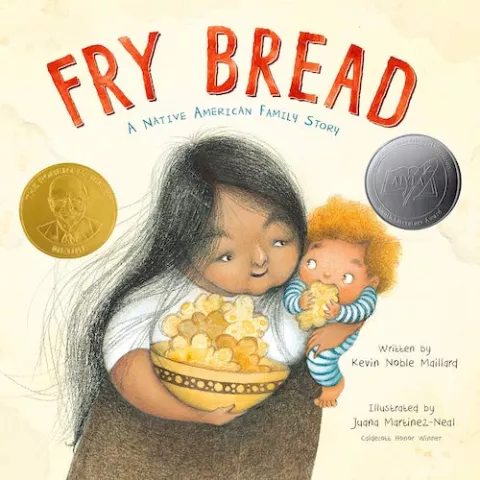

Among those banned books are more than two dozen recommended by NEA’s Read Across America. These books, endorsed by the experienced educators serving on NEA’s Read Across America (RAA) committee, range from the sweet picture book, “Fry Bread: A Native American Story,” to the relatable middle-grades book, “Stella Díaz Has Something to Say” to the riveting young-adult book “The 57 Bus: A True Story of Two Teenagers and the Crime that Changed their Lives.”

What all of these book have in common is this: They reflect the diverse experiences of students of all races, of all abilities, of all religions. They open windows in students’ minds, so that we can see—and celebrate—all of us.

“As an immigrant kid, I wish I had seen somebody who looks like me in a story… a Latina girl with the same possibilities as everybody else. I loved to read and I believed in the stories I read,” says Ovidia Molina, a Texas middle-school history teacher and RAA committee member who serves as president of the Texas State Teachers Association.

How This Hurts Students

The intent of Banned Book Week—to celebrate the freedom to read and to highlight the value of free access to information, even when it’s unpopular or unorthodox—has never been more current or critical.

Today, the issue isn’t just the quantity of bans, PEN America notes. It’s about how these bans are instigated by politicians and embedded in legislation. These politicians like to say they’re representing parents, but parents’ concerns have been addressed for decades through established school policies. Instead, these efforts seem intended to generate headlines and campaign donations, and to divide parents against educators.

“All of our schools want parents to be involved. If parents have real issues with a book, we want them to bring it to the school’s attention,” says Molina. “In Texas, it was specifically a politician who brought this up, who has changed the story to say that we, schools, are trying to do something parents don’t want. But that’s not the real story. All along, we have had processes for parents, and we also have parents who actually want to see themselves and their families in books.”

In reality, national polls show that parents and community members overwhelmingly trust educators to make the right choices about books and curricula. Instead of banning books or historical topics like slavery, the majority of voters—across political parties—want their elected officials to come up with real solutions to serious issues in education, like school shootings and a lack of funding for basic things.

“For us [in Texas], the censorship started in history classes, but it’s spread like the plague,” says Molina. And the effects go beyond the removal of books, she points out.

The proliferation of bans and challenges—and of laws like Florida’s Stop WOKE law, restricting what teachers can teach—means her colleagues are fearful and hesitant to address students’ concerns about history, identity, or more. Educators engage in “soft censorship,” or the practice of avoiding any content that might lead their state representative to call them out on Facebook or school officials to search their classroom desks.

All of this hurts students, Molina said. “The idea that we don’t want to give our kids as much information as possible is hurtful,” says Molina. “If we, as educators, have to tell our kids we’re limiting information, then first, they’re going to find it somewhere else. The information is out there.

“And then second, we won’t be seen as the person they can come to. We won’t be able to ensure that our kids are safe and getting information that is accurate.”

“I Will Continue to Fight.”

Last fall, a Texas state representative came up with a list of 850 books that he said would make students feel “guilty” or “uncomfortable,” and he asked districts to report whether those books could be found in their libraries or classrooms. Five of those books were written by Read Across America-recommended author Bill Konigsberg.

One is “The Bridge,” a young adult book about two teenagers, strangers to each other, who meet on a bridge where they plan to die by suicide. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among teenagers in the United States, and experts say that not talking about it is exactly the wrong strategy. Two other Konigsberg books on the Texas list are “Openly Straight” and “Honestly Ben,” whose main character is a label-defying LGTBQ+ teen who plays soccer, hangs with his friends, and loves his parents.

Konigsberg, who is gay, didn’t have these kinds of books when he was a kid, he says. But having them could have prevented his victimization. “I didn’t see myself at all [in books], and that’s why I became this writer. The truth is I wanted other kids to have more resources than I did.

“This is hard for me to talk about, but it’s true. The fact that [book banners] are using terms like ‘pedophile’ and ‘grooming’ enrages me. Frankly, I was someone who was groomed. And if there had been books like mine, I wouldn’t have been. I would have known what’s going on.”

Konigsberg prepared a statement in anticipation of his newest book, “Destination Unknown,” which takes place during the AIDS epidemic, at a time when hateful people isolated, scorned and mocked gay men. Today, those same people are banning books, he said. “They were shockingly selfish, mean spirited and morally reprehensible then, and that hasn’t changed one iota,” he wrote in the statement.

What they don’t understand is that “these books save lives,” he says. Konigsberg gets letters from readers—young LGBTQ+ people—who tell him, “This book changed my life. This book saved my life. I saw myself in this character and I never saw myself on the page before.” Konigsberg takes these letters seriously. He is familiar with the research that shows nearly half of LGBTQ+ kids serously considered suicide in 2021.

“I will continue to fight to ensure that books that represent all kids remain available in libraries for the teens who desperately need them,” he promised.

Looking for a Book to Read?

Other books on the Texas list include the award-winning “An African American and Latinx History of the United States,” by NEA member Paul Ortiz, a University of Florida history professor and president of its faculty union.

Also, “How to Be An Antiracist” by Ibram X. Kendi and “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” a book about caste systems in the U.S. by a Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter. (The book Caste also appears on very different lists, such as Oprah’s Book Club picks and People magazine’s 10 books of the year.)

Other RAA-recommended book, which have been banned or removed from classroom, include the following titles. Find out how they can be taught in class with suggested activities and questions.

My Hair is a Garden, a picture book about Mack, who is teased for her unruly hair. The book explores themes of identity and courage.

Julián Is a Mermaid, a picture book about Julián, who makes a mermaid costume out of his abuela’s curtains. The book explores themes of identity and friendship.

Alma and How She Got Her Name, a picture book about Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela, and how all of her names connect her to her family. Themes include culture and identity.

When Stars Are Scattered, a middle-grades book with two brothers—one nonverbal—who fled Somalia and are determined to get an education beyond their Kenyan refugee camp. Themes include immigration and family.

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, by Jason Reynolds, adapted from Ibam X. Kendi’s work, is a young-adult book that uses humor to explore America’s racist past. Themes include racial and social justice.

I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, a National Book Award finalist for young adults, in which a rebellious daughter deals with her family’s grief, after her sister’s death. Themes include culture, trauma, family and identity.