Educators Demand Smaller Classes

A few years ago, Kathia Ruiz had a whopping 29 students in her fourth-grade classroom. Through some lucky twist of fate, the Woodburn, Ore., teacher started the 2022 – 2023 school year with only 18.

“It was amazing all the things I could do! The differentiation that was possible,” she says. To her, the benefits of fewer students in a class are clear.

But when Ruiz and other members of the Woodburn Education Association bargaining team sat down with district administrators, the district didn’t—or wouldn’t—see it. Their lack of consideration was “mind-blowing,” she says. “[Class size] has such an impact on what teachers can do. We want to support every student.”

Across the nation, educators agree. In Columbus, Ohio, in fall 2022, teachers went on strike to get smaller class sizes. A month later, Massachusetts educators in the cities of Malden and Haverhill did the same.

In Spring 2023, in both Woodburn and 20 minutes away, in Silverton, Ore., union members were on the verge of striking. Finally, the district agreed to contract language that mandates specific supports when a class exceeds a certain number of students.

Whether at the bargaining table, in the halls of state capitols, or in other places where educators and parents confer about things that matter, class size is a hot topic.

“We haven’t seen this historically—until this year,” notes NEA’s Andy Jewell, a collective bargaining specialist who has tracked educator strikes for decades. “This year, in almost every strike and near-strike, class size has been a big issue. It’s more prominent and more significant.”

The root cause of the uptick is unclear, though the national teacher shortage and the spike in students’ needs since the pandemic have likely contributed.

What is certain is that educators and parents agree that smaller classes and special education caseloads would help students succeed.

“Teachers have to demand what they know is best for the students. Nobody else is coming to save us,” says Alison Stolfus, president of the Silver Falls Education Association, in Silverton. “You have to get organized and demand it!”

Voters across party lines have positive views of public schools and educators

More than 70 percent of voters (both parents and non-parents) have a favorable view of public school teachers—and their views are more positive this year than last. That’s according to a national NEA poll, conducted in August, of 1,400 likely voters in the 2024 elections.

Public school teachers received positive ratings across partisan lines, including among 70 percent of independents and 60 percent of Republicans. Only 13 percent of independents and 16 percent of Republicans view public school teachers unfavorably.

| Party | Favorable | Unfavorable |

|---|---|---|

| Democrats | 86% | 5% |

| Independents | 70% | 13% |

| Republicans | 60% | 16% |

Teachers Work More Hours Than Other Working Adults

In a national survey released by the RAND Corporation, in September, K–12 public school teachers reported feeling overworked and underpaid. On average, they estimate working 53 hours a week—seven more hours than the typical working adult. (RAND conducted a separate survey of all working adults.) Only 24 percent of teachers are satisfied with their total weekly hours worked, compared with 55 percent of all working adults.

The survey also found that about a quarter of teachers’ time is uncompensated, and 66 percent say their base salary is inadequate, compared with 39 percent of all working adults. Of those respondents who are thinking of leaving the profession, 54 percent said working too many hours outside the school day was a factor in their dissatisfaction. Sixty percent said the same for low pay.

Quote byPEN America

Educators Still Buying Their Own School Supplies

Studies show that on average, educators spend from $500 to $750 of their own money every year on things students need. And many educators spend a great deal more. Out-of-pocket classroom expenses are greatest during the back-to-school time period and continue to add up throughout the year.

Where does the money go? Educators report buying clothing, winter gear, eyeglasses, food, and toiletries for students on top of classroom supplies and teaching materials. To make matters worse, due to high inflation, prices for school supplies increased almost 24 percent since 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That’s made back-to-school shopping hard on many families, and difficult for educators—already stretched thin by low pay—who often subsidize their classrooms.

Some NEA locals have taken on the issue of educators’ out-of-pocket classroom costs during bargaining. When successful, it brings substantial relief to educators.

The Cascade Education Association, in Washington, bargained successfully for annual funding for classroom spending. That helped Vicki Harrod, a second-grade teacher in Peshastin, Wash.

“Our district gives us $350 to spend on whatever we want and another $150 for essentials, like construction paper and so on,” Harrod says.

Many educators have turned to online resources, such as DonorsChoose, Amazon Wish Lists, and AdoptAClassroom.org, to ask for donations. While this may save educators some of their own money, it does require an investment of time to set up and repeatedly promote their online campaigns.

Still, educators are grateful for the support.

Memphis, Tenn., teacher Rita Elle procured about $600 worth of supplies through her Amazon Wish List this year, noting that nearly all of the items were purchased by friends and family.

Victory for Portland Teachers!

Tiffany Koyoma-Lane gets her first minutes of planning time each week about halfway through Wednesday. Until then, she scrambles to make it work for her third graders at Sunnyside Environmental School, in Portland, Ore., who have numbered as many as 31 per class in recent years. Special education educators are quitting in droves. Classrooms have rodents, mold, and temperatures that regularly exceed 90 degrees or fall below 60. And the pay isn’t great!

For these reasons and many others, the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT) went on a historic strike in early November, after months of fruitless negotiations with Portland Public Schools. Their top issues? Decreasing class sizes and increasing planning time so that all students can get the attention they need; raising pay so teachers can afford to stay in Portland; and making schools safe.

Ninety-nine percent of PAT members had voted to strike, and polls showed that more than 90 percent of Portland parents and community members supported the strike, too. Thousands of union members picketed loudly and proudly, alongside parents, students, and community members.

They won, of course. Like NEA President Becky Pringle told PAT members, as she rallied alongside them: “When we fight, we win!”

Does Restorative Justice Work?

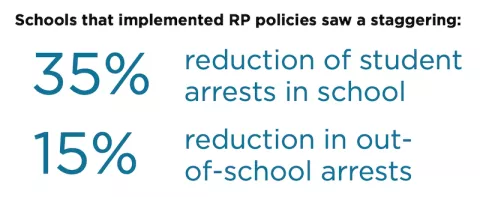

It has been more than a decade since school districts began implementing restorative justice practices—focused on building relationships, conflict resolution, and social and emotional learning—as an alternative to exclusionary discipline, or “zero tolerance” policies. But is it working?

In Chicago Public Schools, the answer appears to be yes. Researchers at the University of Chicago Education Lab found that restorative practices, adopted in the 2013 – 2014 school year, have resulted in a staggering 35 percent reduction in student arrests in school and a 15 percent reduction in out-of-school student arrests. Students reported that school climate also improved. They felt a greater sense of safety and were more likely to feel they were members of a community.

Rising Confidence in Student Academic Recovery

Improving post-pandemic learning has been a complex and arduous challenge for educators, parents, and students across the nation. But according to a survey conducted at the start of the 2023 – 2024 school year, educators expressed optimism that students may soon be where they need to be academically. Sixty-seven percent said they were “very confident” or “somewhat confident” that their students would reach grade level during the school year. Still, educators’ confidence in this outcome was lower than before the pandemic, and schools still face formidable obstacles—including educator shortages and the looming expiration of federal relief funds.