Working Together Benefits Our Students

Educators want to have a voice at the table when decisions are made. The problem is that traditional school hierarchies encourage top-down decision-making that doesn’t take educators’ expertise into account.

This systemic disempowerment of the nation’s educators contributes to widespread turnover in the teaching force, which is detrimental to student achievement.

So how do we change this culture? Enter labor-management collaboration.

The benefits of labor-management collaboration

“Eight years ago, NEA set out to study and learn from all of the best collaborative practices happening around the country,” says Andrea Walker, NEA’s director of strategic engagement. “We found that having structures to support collaboration is really what’s key.”

“Labor-management collaboration is not about always getting along or about individual relationships, although that may be how it starts,” Walker adds. “It’s about making a commitment to be transparent and inclusive by bringing stakeholders to the table to have an equal voice.”

“Labor-management collaboration ...is about making a commitment to be transparent and inclusive by bringing stakeholders to the table to have an equal voice.”

Research showing the benefits of such partnerships and a lasting culture of working together.

According to a 2017 Rutgers University study, these positive outcomes include:

- Increased student achievement;

- Improved educator retention, particularly in high-poverty schools;

- Increased educator empowerment; and

- A transformed role for local unions, which tend to thrive in a culture of collaboration.

3 Paths to Productive Labor-Management Collaboration

An ongoing dialogue

And labor-management collaboration can complement traditional collective bargaining, the process through which educators and their employers negotiate agreements.

Collaborative practices support productive conversations between the union and school districts outside of contract negotiations.

These conversations can strengthen ties between district leaders and union members, giving educators a voice beyond the scope of bargaining.

In the earlier days of the pandemic, some NEA locals engaged in collaborative practices to secure safer conditions and to keep students learning and educators working. They also advanced the march toward racial and social justice in schools.

These successes offer a vision for what healthy labor-management relationships can look like—and a model that your local may be able to replicate.

3 States, 3 Different Approaches

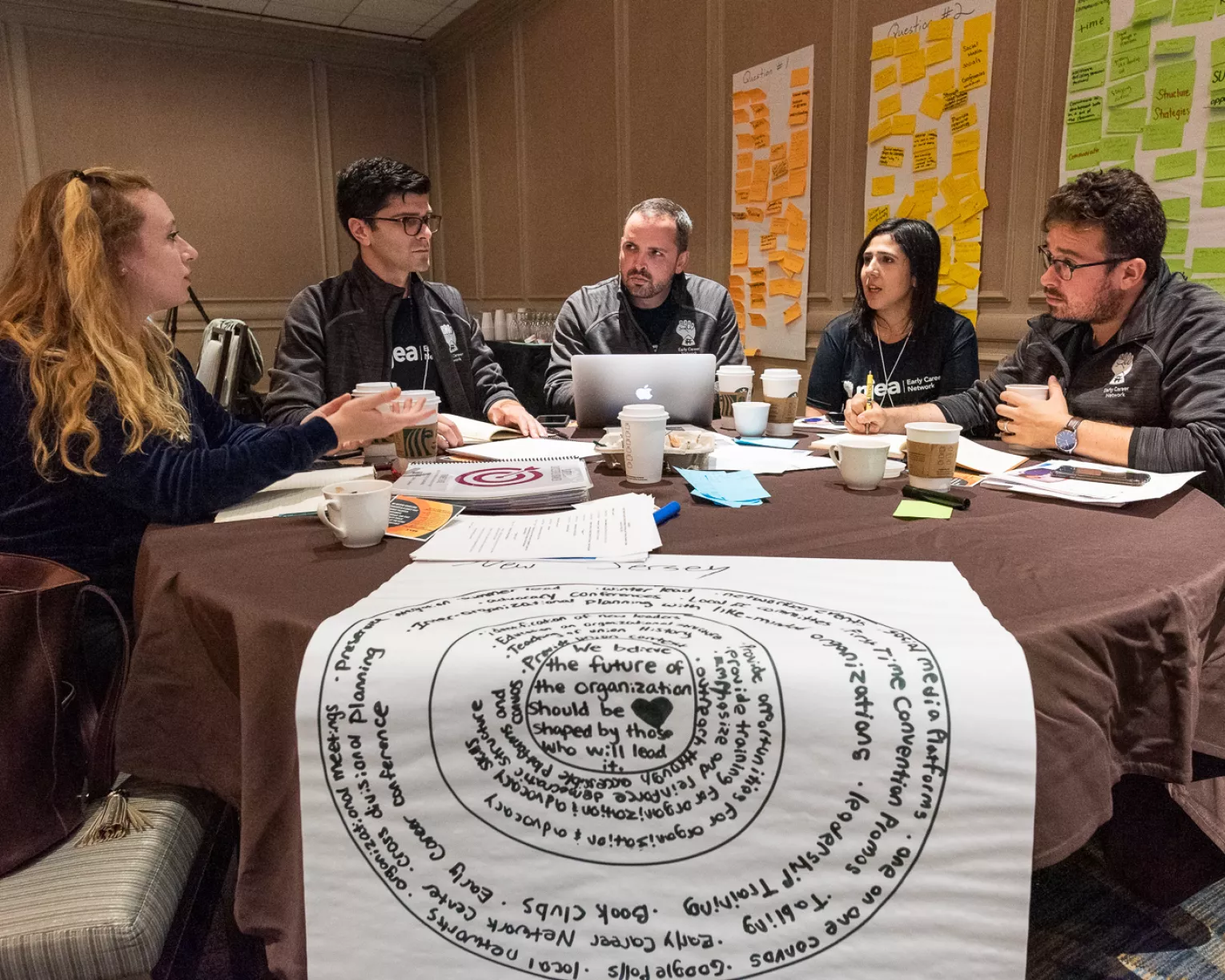

New Jersey local leveraged existing collaborative structures

Like most schools in the nation, the Montgomery Township Education Association (MTEA) in New Jersey was tasked with figuring out how to deliver virtual instruction and return to in-person learning during the pandemic. But they didn’t let that crisis derail a new initiative to become a more culturally responsive school.

Fortunately, they had long-standing collaborative structures in place to make that possible.

“We prepared staff for the uncertainty of COVID conditions as part of our professional development in August 2020,” says MTEA President Jim Dolan. “We ultimately decided to start that year virtually until October. The decision was not unanimous, but all voices were heard, so we had full buy-in.”

“That honesty never would have happened under a traditional model.”

That team spirit was key when the district’s school leadership team decided to keep working to improve racial equity during the pandemic.

“Something unusual happened,” says Karen Kevorkian, an eighth-grade language arts teacher and a vice president of MTEA. “Several members of color who served on that team expressed that some of our efforts could have the opposite effect of what we intended. So we sought professional guidance and revised our plans,” she says.

They soon realized they needed additional staff training, a cultural audit, and equity teams in each building as well as the district-wide team.

“That honesty never would have happened under a traditional model,” Kevorkian says. “With that came authenticity and true progress, not just checking a box and moving on.”

Building off traditional union tactics in Wisconsin

In Wisconsin, Racine Educators United President Angelina Cruz has worked to improve relationships and increase collaboration with administrators since she was elected five years ago.

During the pandemic, though, the local association used more traditional union tactics to kick-start action on health and safety. First, safety representatives were identified. They conducted walk-throughs in every school building, using a checklist that NEA helped develop. Then the local filed 112 first-step grievances to convey how concerned they were over safety issues, Cruz says.

Because she had worked to establish collaborative relationships, Cruz found a willing partner in Chief Operations Officer Shannon Gordon. “She took our concerns really seriously,” Cruz says.

This work led to a wide range of improvements across the district’s 31 buildings—some of which are pre-Civil War structures. The district secured paper towels and other supplies for handwashing, fixed water faucets, increased spacing between students’ desks, identified unusable spaces, and repaired broken HVAC vents.

Collaborative work during the early days of the pandemic was the ultimate trust-building exercise

“We looked carefully at our cleaning protocols and completed more than 12,000 work orders,” Gordon says. “But the greatest success that we had is we created a comprehensive team of more than 100 stakeholders who came together to develop our Smart Start 2020 building reopening plan.”

Collaborative work during the early days of the pandemic was the ultimate trust-building exercise, Cruz says. She constantly communicated information and results back to her membership, so they would understand that administrators were listening and building improvements were being made.

“Our building safety reps will stay in place for the foreseeable future,” Cruz says. “It’s not like the pandemic is over.” Racine Educators United President Angela Cruz (right) and Chief Operations Officer Shannon Gordon worked together to address the district’s aging HVAC system.

North Carolina local stood up in a state without collective bargaining

How do you fight for educator and student safety during a worldwide pandemic when your state has a total ban on public sector bargaining?

That’s the scenario facing the Pitt County Association of Educators (PCAE) in North Carolina, where labor-management collaboration is in the early stages. Right now, it hinges on a few close relationships.

“We’ve been able to build a great relationship with the superintendent and with some of our board of education members, all trying to come together for this common purpose,” PCAE President Lauren Piner says. “Education shouldn’t be partisan, but in many states, including North Carolina, it has become very partisan.”

“You can always get up and walk away, but you’ll never know what relationship you missed out on if you aren’t willing to come to the table.”

Piner’s ability to convey members’ concerns directly to the superintendent resulted in three key wins during the COVID-19 crisis: A two-week delayed return to school buildings in January, to protect student and educator health; securing personal protective equipment for educators; and allowing entirely virtual job duties for members with medical issues.

The union has also worked closely with the local chapter of Parents for Public Schools. “Sometimes when people aren’t willing to listen to educators, they will still listen to parents,” Piner says.

Her advice to other locals? “What it comes down to is saying yes to coming to the table,” she says. “You can always get up and walk away, but you’ll never know what relationship you missed out on if you aren’t willing to come to the table.”

Collaborating for Student Success

Collaborating for Student Success

Get more from