Key Takeaways

- Research finds that police officers in schools do not make school safer and leads to harsher discipline for minor infractions.

- NEA's Aspiring Educators have found ways to take action.

Cameo Kendrick remembers the uneasy feeling of seeing police officers walk the halls of her high school. The same feeling came over her recently as she visited schools in her hometown of Lexington, Ky., where she plans to teach and send her two children.

“It is frightening, especially for a Person of Color,” Kendrick says. “And, as I’ve grown to understand this issue, I also know that it has deep roots in racial injustice and is a cog in a system that unfairly and more severely disciplines minority students.”

Kendrick, who is chair of NEA’s Aspiring Educators (AE), says she and other new educators believe this is a critical social justice issue.

“We’ve chosen to teach so that we can educate and guide young people. [Racial injustice] is antithetical to that,” she says.

Kendrick has found ways to take action, making the issue a priority with AE’s 40,000 members and drawing attention to the problem in her local school district.

“There are … more valuable ways to use money and resources in education to support students and still have safe schools,” she says. “The data clearly shows that these officers—often well-meaning—don’t improve discipline and … their presence often damages the school climate.”

A Growing Problem

Over the last two decades, schools in the U.S. have increasingly employed school resource officers (SROs), often from the local police department. Their numbers have grown dramatically, driven by school shootings and a sense that students are too unruly.

In 1975, only 1 percent of U.S. schools reported having SROs, but that number rose to about 36 percent by 2004, and to 58 percent by 2018, including 72 percent of high schools. These increases are due in large part to more than $1 billion in federal funding for SROs.

Yet research shows that SROs do little to reduce on-campus violence or mass shootings, and their presence is often damaging to students of color and students with disabilities. Having SROs in schools can actually create higher rates of behavioral incidents and spikes in suspensions, expulsions, and arrests.

While limited research suggests that SROs diminish bad behavior and are more likely to spot illegal activity in schools, other data show that students in vulnerable groups are more likely to be harshly punished.

According to a 2017 report, Black students comprised about 15 percent of the

student population, but they accounted for 33 percent of the arrests in schools.

Meanwhile, incidents of SROs using excessive force with students have driven stronger opposition to their presence and have raised fears that they make schools less safe.

In a survey of students in California, 61 percent of White students said they felt safer with a police officer at school, but only 41 percent of Black students

felt more comfortable. And a Tulane University study found that 77 percent of White students in New Orleans felt safer with school security guards, while only 54 percent of Black students did.

Taking Action

Kendrick organized a session on school policing at the AE annual conference in June 2021. One of the speakers, NEA senior policy analyst Aaron Dorsey, said the justification for SROs has shifted over the last 20 years. The original goal

was to improve relationships between students and police, but now the SROs’

role is to control student behavior and reduce crime.

But arrests nearly triple when SROs are present, and students of color are much more likely to be referred to the officers, Dorsey added.

“SROs are not perceived by students as contributing to keeping the school drug-free or improving school safety,” he explained. “Law enforcement creates more hostile environments, and when students perceive their schools to be hostile, they are less likely to be engaged in school and, in turn, demonstrate reduced achievement.”

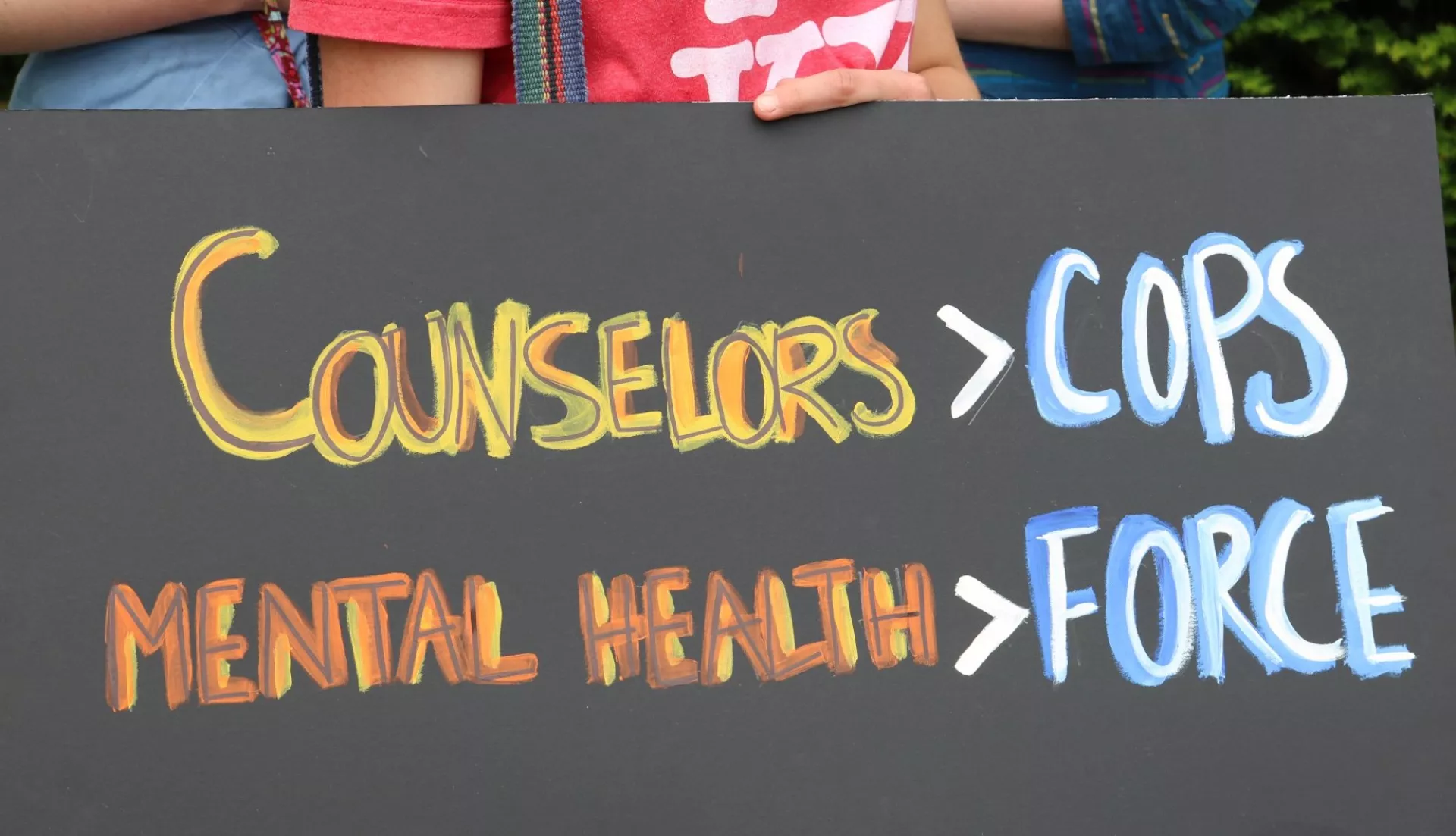

As part of her AE role, Kendrick has worked closely with students in several Kentucky schools to call for SROs to be replaced with counselors. At Lafayette High School, in Lexington, she co-founded the organization Counselors Over Cops, in 2020, with then-senior Micheline Karenga.

“Zero-tolerance disciplinary policies—where school officials simply criminalize minor infractions of school rules—have become a staple in [our nation’s] schools,” says Karenga, who is now a first-year student at Texas Wesleyan University. “These measures [have] … inflated the school-to-prison pipeline, a phenomenon in which students are pushed out of school and into the criminal legal system. Not surprisingly, the students most harmed by these policies and practices are students of color.”

Fortunately, several school districts across the country have already moved to stop the practice.

For more information, visit NEA EdJustice