Key Takeaways

- Educators nationwide have been underpaid, undervalued, and under-resourced for years, leading many to exit the profession.

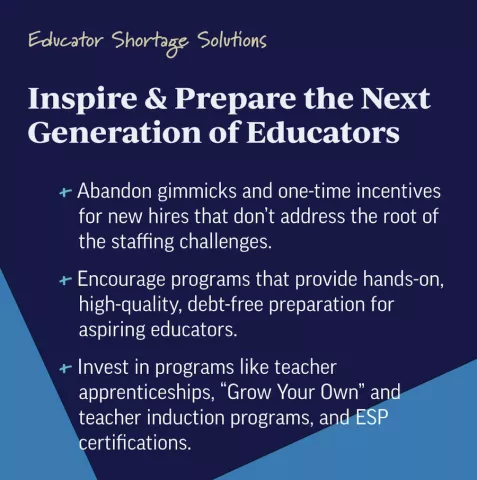

- Recent efforts to address the growing crisis have relied in large part on ineffective stopgap measures and even gimmicks. Educator shortages will only be fixed with systemic, sustained solutions, said NEA President Becky Pringle.

- This week, NEA released a white paper outlining a wide variety of evidence-based, long-term strategies and solutions to recruit and retain educators.

Last week, the U.S. Department of Education confirmed what anyone who works in public schools has known for some time: The nationwide educator shortage is as dire, if not worse, as initially feared. The federal survey found that 53 percent of public schools reported being understaffed at the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, and 60 percent said they had been grappling with open support-staff positions since the start of the pandemic.

A National Education Association (NEA) survey sounded the alarm back in February when it found that a staggering 55 percent of educators—teachers and education support professionals (ESPs)—were thinking of leaving the profession earlier than they had planned.

In his 26 years in the classroom, Ohio high school teacher Dan Greenberg has never seen anything like it. “Across the board, there have been significant drops in the number of applications for open positions in my school district,” he says. “We have been unable to fill certain positions like special education, media specialist, and gifted education. But even subjects that [used to be] relatively easy to attract teaching candidates are going unfilled. It’s unprecedented.”

Unfortunately, these “unprecedented” shortages could become the new normal unless the nation finds a way to address the recruitment and retention crisis plaguing our schools.

This week, NEA released a blueprint on how to get us there. The white paper outlines long-term strategies and solutions that are effective at recruiting and retaining educators. Most importantly, the strategies reflect the needs and priorities of educators themselves.

This is not about temporary pay bonuses, putting unqualified individuals in the classroom, increasing class sizes or increasing the caseload or workload on already overtaxed educators.

What is needed is a comprehensive strategy that targets long-standing structural deficiencies that have made the profession undesirable, says NEA President Becky Pringle.

"Too often people want a silver bullet solution or will implement a Band-Aid approach. These shortages are severe," Pringle says. "They are chronic. And the educator shortages gripping our public schools, colleges and universities will only be fixed with systemic, sustained solutions."

It Starts with Better Pay

Delaware recently approved a 3 percent pay raise for school bus drivers. It was welcome news, said Jeanette Schwartz, a driver in New Castle, but “we still live under the poverty line.”

"Working 12-hour days as a school bus driver, I will make just over $20,000 this year. Quite simply, school transportation staff are overworked and underpaid! In a typical school day, bus drivers do three to four runs in the morning and another three to four in the afternoon,” says Schwartz.

According to NEA research, in 2020-21, more than 40 percent of full-time, K-12 ESPs earned less than $25,000.

For classroom teachers, choosing the profession means incurring what is known as the "teacher pay penalty"—the percentage by which public school educators are paid less than comparable workers. According to the Economic Policy Institute, this gap has reached an all-time high. Teachers on average now earn 23.5 percent less than comparable college graduates.

Inadequate pay forces too many educators to take on one, if not two, more jobs just to make ends meet. According to an NEA survey, 41 percent of pre-K–12 teachers and 37 percent of ESPs held two or more jobs in 2019. "The educator recruitment and retention crisis can be, in part, blamed on the fact that many educators can make more money in less-stressful jobs outside of education," the NEA white paper says.

Research has consistently shown that states and districts with higher teacher salaries have higher levels of student achievement. While time-limited bonuses are welcome, they are a stopgap, not a solution.

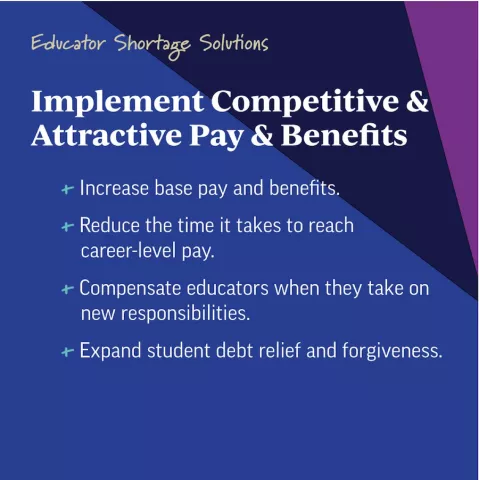

NEA is urging all districts to implement schedules with competitive starting salaries, rewards for professional development, and competitive mid-and late-career earnings.

Knowing that their salaries will be competitive will attract more qualified individuals to the profession, but retaining those educators could depend on how quickly they reach the top of their pay scales. It shouldn't take 20 years to reach career-level pay. A shorter schedule will help shrink the pay gap with other professionals and boost retention efforts.

It should not stop there. NEA is also calling for an end to an unjust, outdated federal pay regulation that excludes pre-K-12 teachers and higher education faculty from receiving the same wage protections as other professionals.

Student Debt Relief and Affordable Housing

The Biden administration's recent action on student debt cancellation was "an encouraging step," says Pringle. But much more needs to be done. Overall, more than one-half of teachers and almost one-third of ESPs borrowed to pay for higher education and many carry an almost unmanageable debt. The prospect of crushing debt must be minimized if educator recruitment and retention efforts are to be successful.

NEA is calling on the federal government to enact much broader student debt cancellation (up to $50,000), support educator applications for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) waiver, and encourage school districts to use their CARES Act funds (the COVID economic relief package signed into law in March 2020) to pay for or reimburse employees' student loans.

NEA is also spotlighting the urgency behind affordable housing. In too many school districts, school staff simply cannot afford to live where they work. Prohibitive housing costs have proven to be a significant obstacle in recruitment, particularly in notoriously expensive parts of the country.

“We’ve been advocating for a long time for affordable housing for educators,” says Terri Baldwin, president of the Palo Alto Education Association in California. “We’ve got people living all over the Bay Area. They’d love to go evening events and be present in their schools, but it’s hard to be involved in that way when you have a 2-hour drive!”

More pay would obviously help, But NEA is also advocating for other strategies, including the development of teacher or employee housing and tax incentives for living in the communities where educators work. In Palo Alto, teachers will soon have access to a new 110-unit apartment building. Similar developments have appeared in other parts of the country.

Better Working Conditions

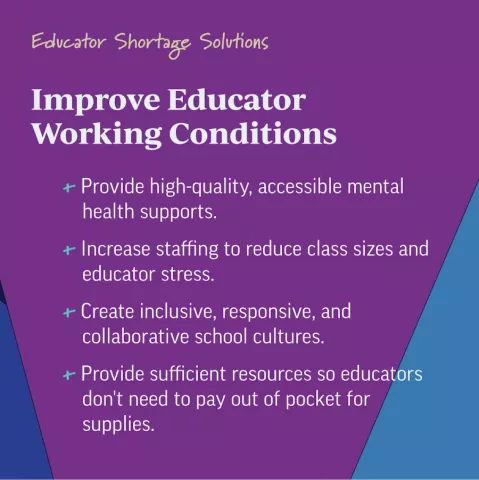

A 2022 RAND survey found that teacher well-being was much lower than other working adults and, a major catalyst in their decision to leave the profession. Mid-career teachers were most likely to report symptoms of depression, frequent job-related stress, and feeling less resilient and less able to cope. A school‘s adverse working conditions—crushing workloads, less time for teaching, and lack of support and autonomy—often drive these feelings of hopelessness, burnout, and demoralization.

Research shows that school leaders who protect teachers’ time, invite their input, and support their mental health and well-being through comprehensive programs see higher levels of satisfaction.

As with other drivers behind the educator shortage, unfavorable working conditions did not originate with the pandemic, but the demands on educators over the past two years increased exponentially, pushing many to their breaking point. "The pandemic has revealed that the only reason the education system isn’t crumbling down is that teachers and school staff are holding it together,” Nicholas Ferroni, a teacher in Union City, New Jersey, says. “We had the same impossible expectations as previous years, but then society and school administrations added on more and more.”

Increasing staff levels to alleviate stress is paramount. More teachers means lower class sizes and that students can receive more one-on-one instruction time. The NEA report also urges districts to hire more paraeducators, school counselors and psychologists, nurses and bus drivers.

“By increasing the numbers of staff in these positions, the entire system would be able to help support students and staff cope with their own trauma and wellness,” the report states. “Adding more permanent staff can relieve much of the stress placed on educators by making caseloads more manageable and curtailing long workdays.”

Mirroring other research, the RAND survey found teachers of color were more likely to consider leaving the profession than their White counterparts, due in large part to school climate—specifically the exposure to racial discrimination and other sources of race-based stress.

NEA calls on districts to reverse these disturbing trends by implementing policies that promote culturally responsive and inclusive workplaces, revise curriculum to include under-represented populations, diversify school leadership roles, and provide racial and social justice-centered professional learning.

Autonomy and Respect

While many, if not most, of the factors behind educator shortages predate the COVID pandemic, the increasingly toxic political environment has left many public school educators even more stressed, vulnerable, and disrespected—and more likely to head to the exits.

It has been a "gut punch," says Alejandra Lopez, a teacher in San Antonio, now in her fifth year in the classroom.

“Teachers are in the middle of a polarizing political landscape, and the attack on educators has increased the pressure and stress we feel daily," she explains. "Dictating what we can teach in our classes, banning books, and disrespecting our craft have become breaking points for many educators. Teachers need to be treated as professionals instead of being used as a political football.”

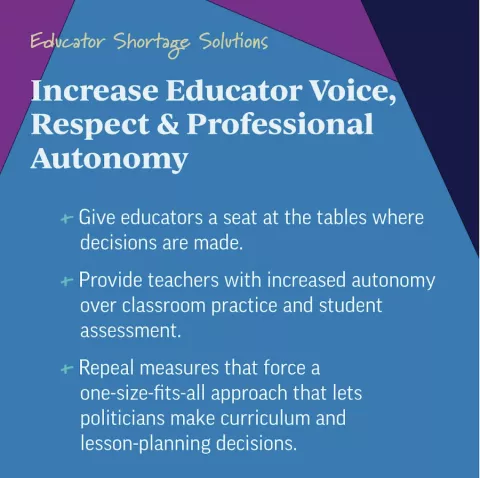

The recent assault on America’s classrooms to root out honest discussions about race and turn back the clock on inclusion has gained traction, in large par,t because of the pervasive lack of respect and autonomy that has undermined the teaching profession for years, if not decades.

Surveys show that educators whose voices are valued and respected are more likely to report higher levels of job satisfaction, whereas those who do not have significant roles in setting curriculum and determining what they teach in class are more likely to quit.

Education has fundamentally changed, and the systems that surround it must be restructured. We must build an education pipeline for the future—one that recruits diverse, well-prepared educators to remain in a respected profession that values its educators and supports and pays them accordingly. — "Evaluating the Education Professions," National Education Association, 2022.

In addition to improving overall working conditions for all educators, NEA is urging schools and districts to give teachers more input into basic decisions, such as curriculum and other ways to structure their classroom. Teachers are professionals with expertise who know better than anyone how to tailor lesson plans and what subjects to address to ensure success in the classroom.

Educators should also have a say in school-wide policies covering discipline, the content of professional learning opportunities and evaluation.

“We need to enhance, not cut, curriculum, [and] rethink evaluations and how we can provide multiple models of support for educators,” says Sobia Sheikh, a math teacher in northwestern Washington.

The NEA white paper says establishing or expanding collective bargaining is critical if educators are to have a voice at the table. Collective bargaining fosters unity and strength at the local level, says Sheikh. “Our power is in our local association and building relationships with the community."

Those partnerships will be critical in building the necessary support and commitment to restructure the systems that have devalued the education profession and put public education back on the right track.

“Educators, parents, and communities are coming together and demanding long-term solutions to long-term problems,” says NEA President Becky Pringle. “Together, we can build a world where all students have the support they need to recover from the academic, mental, and social impacts of this pandemic and overcome decades of failure by some politicians to fully support our public schools.”