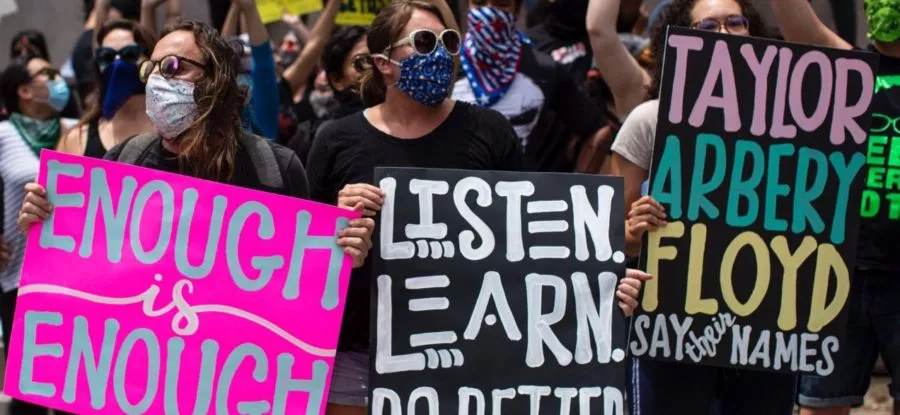

Within a few months, the world saw egregious attacks on black Americans:

Feb. 23: While out on a jog—Ahmaud Arbery, a black man, was shot and killed by two white men with ties to the local police department. Arbery’s case made national news on May 5, when a 28-second cellphone video capturing the killing was leaked onto social media.

March 13: Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency medical technician and a black woman, was shot eight times and killed by Louisville Metro Police during a late-night, “no-knock,” forced entry on her home. The warrant did not include the victim’s name and was issued for another home miles away. And, the person the police were looking for was already in custody. Taylor’s death also made national news in May.

May 25 (morning): Amy Cooper, a white woman, called the police on Christian Cooper (no relation), a black man, in Central Park during an encounter involving her unleashed dog. Christian Cooper recorded the encounter in which he is largely silent while she tells police he is threatening her and her dog. Amy Cooper is heard saying, "I'm going to tell them there's an African American man threatening my life."

May 25 (afternoon): George Floyd, a black man, was killed in broad daylight when an officer from the Minneapolis Police Department pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds. The officer did not remove his knee even after Floyd lost consciousness.

These attacks on black bodies—plus those that have gone untelevised, ignored, excused, or denied—is not new ground for most people of color. In fact, they are reminiscent of the racial terrorism and intimidation black Americans have experienced since the founding days of this country.

“This is no time for us to look away," says NEA President Lily Eskelsen García. "Police violence against black people happens too often. The threat and real violence toward black people daring to exist in public spaces and even in their own homes is the direct result of how white supremacy culture is the air we breathe in America."

She adds, “As a union of 3 million educators, stretching across the country, to every community, we have an obligation to act. Together we will continue the call for justice and to hold powerful people to account."

“This is a horrifying, senseless death that shows once again the racism that black, brown, and indigenous Minnesotans live with every day,” says Denise Specht, the president of Education Minnesota, of the murder of George Floyd. “We anticipate our students of color will experience trauma from this killing as they did with Philando Castile, Jamar Clark, and too many other black men who died in police custody,” adding that “educators will once again do our best to help our students through, but this must stop.”

And educators are certainly equipped to help make it stop, says Catina Neal, a special education assistant in Minneapolis.

An End to Policing Schools

It’s been well documented that black and Latino students are more likely than their white peers to be suspended, arrested, and disciplined in school. This likelihood increases for students of color and other marginalized students when school police officers are added to the mix, according to a 2018 report titled “We Came to Learn: A Call to Action for Police-Free Schools,” by the Advancement Project and the Alliance for Educational Justice.

The report underscores how across the country black and brown students are more likely to be arrested by police, and details how police in schools disrupts learning environments: when police are called into a situation they often rush to criminalize youth behavior, and arrest rates for low-level offenses substantially increase when police are assigned to schools. Additionally, routine school discipline matters have often been met with unwarranted arrests and excessive force.

Catina Neal

Catina Neal

After the death of George Floyd, the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, local 59, joined other organizations in calling for the city’s public school board to break ties with the police department, which it did. The school board unanimously approved a resolution to end the district’s contract with the city’s police department to use officers to provide school security.

Helping to influence this charge was Catina Neal, an educator of 21 years. Neal is a a member of the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers and a long time organizer who has pushed an agenda of social justice and equity for Minneapolis public schools.

She motivated educators—who are tired of the oppressive laws and policies that harm black Americans—to share their broader story with school board members.

“They’re fed up with the entire country treating us as three-fifths of a person…and we just want to see change,” she explains, adding that it wasn’t just about cutting ties between the Minneapolis police department and the school district.

“It’s about the injustices that have been going on for years, decades, and centuries,” says Neal. “It’s bad enough our children see the police harming African Americans or their brothers, uncles, and fathers in their homes or on the streets…and then get to school and have it happen to them—that’ a huge mental health concern,” says Neal.

Neal is hopeful that the grassroots organizing witnessed across the country will lead to the fair treatment of black Americans and shares, “There’s going to be some huge changes.”

Educators Can Help Dismantle Institutional Racism

“How we navigate this moment is going to set us up for how we approach the future,” says Tamika Walker Kelly, a music teacher in North Carolina, “and educators have the ability to lay the groundwork to help our students understand what is happening in the world now and how they will be the catalyst to change the future.”

She adds, “We have to equip students with the language and tools to create the world that is necessary for everyone to be respected, loved, and valued—and educators are in the unique position to do that.”

The music teacher of 13 years and the president of the North Carolina Education Association says that in order for change to occur, educators must recognize the biases they bring into the classroom. Change will also come from building true, meaningful, and authentic community coalitions and deepening one’s knowledge of the effects of racism, and “how it not only affects black people and other people of color, but how it affects white people…and understand how all things intersect with one another,” she says.

One of the observations Walker Kelly noted of the protests in cities across the country was that those who protested came from all walks of life.

“It wasn’t just older or younger Americans. It was families, educators, and students coming out into the streets to lift the collective voice,” she says. “It’s a difficult thing for Americans who have been comfortable and complacent in their privilege, but it’s been beautiful to see so many people come together to have the difficult conversations and who are engaged in activism in a way that’s never been done before.”

Minnesota’s Catina Neal shares that her work with her local union has included getting members to recognize their own white privilege and building broad coalitions.

“I can tell you that some of my white brothers and sisters at my job and friends have been very supportive. [During the protests], they stood in the front of me because I was scared of the police trying to get to me first. They protected me…and that’s what I want to see: people speaking up when they see wrong, when they see someone getting mistreated no matter what color they are… and speak up, especially if they’re black.”

Resources

Message from Lily Eskelsen García on Lily’s Blackboard.

Statement of the National Education Association.

Statement by Education Minnesota.

NEA Ed Justices resources such as Black Lives Matter at School, Talking About Race, Implicit Bias, and many more.

Centro de Trabajadores Unidos en la Lucha.

NEA Ed Justice School to Prison Pipeline page, which includes the Restorative Justice Guide.