Key Takeaways

- In most cases, when an educator gives birth or adopts a baby, they must cobble together a few unused sick days, and return to the classroom long before they're ready.

- At local and state levels, NEA affiliates with the power to collectively bargain have fought for contracts that include family leave. Unions also have lobbied for state legislation.

- A national policy doesn't yet exist—but establishing one is a priority of the Biden administration.

Recently, a Northern Virginia teacher sent home a note to parents. Just wanted to let you know, she wrote, that I’m expecting my first baby next week—and will be out of school for three weeks.

Her school district doesn't provide paid family leave, and 15 days off is all that she can afford. And it's not just her. Most teachers, like most workers in the United States, don’t have access to paid family or parenting leave. Instead, like this teacher, they must cobble together a few sick days and a few personal days and return to the classroom long before they’re physically and emotionally ready.

This lack of support, which has been made worse during the pandemic by the increasing need to take days off to quarantine or care for COVID-sick family members, is one of the many reasons that educators leave the profession.

It’s a problem—but one that NEA and its affiliates are tackling. While many local educator unions, such as University of Florida’s faculty union recently, negotiate at the bargaining table for family leave, other unions are advocating at the state level for better state legislation. In Delaware two years ago, the Delaware State Education Association (DSEA) helped push through a law that provides 12 weeks of paid family leave for educators.

A broader, national policy also is a priority of the Biden administration, but one that Congress has failed to address. “We must enact policies that support working people and their families,” says NEA President Becky Pringle, including “a permanent, national paid family and medical leave program.”

"When do Teachers Get to be Human?"

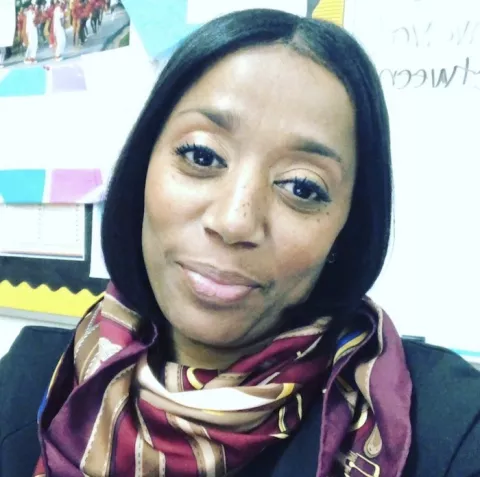

A few years ago, Michigan teacher Teneshia Moore brought home from the hospital an infant named April, who she was fostering and hoping to adopt. Because she was relatively new to her school district—although not at all new to teaching—she had accrued few medical or personal days off.

Moore persisted, but the lack of systematic support almost forced her out of the profession.

Recently, Moore, who has been teaching for 23 years, found herself in a similar strait, struggling to take time off to care for family members infected with COVID-19. First, it was her aunt, who died this spring. Then, it was her mother, who survived—twice. Then, in May, it was her stepfather, who also died.

“It was one thing after the other, and I just did the best I could,” she says.

This fall, Moore also is being told to stay home in quarantine for 10 days—using her own meager medical and personal leave—whenever students in her middle-school science classroom test positive for COVID-19. Meanwhile, like most educators, she only gets about 12 to 15 days a year from the district. “It’s totally unfair—we just don’t have enough days,” she says.

And Moore is far from alone. Many teachers struggle to take care of their own families and their students. “I don’t not want to teach anymore, but I also want to be a mother and have my own family as well,” a Georgia teacher—who had no paid leave after the birth of her second child—told Education Week last year. “There’s the sense that you’re supposed to be heroic about it. When do teachers get to be humans?”

A Patchwork Approach

Unlike every other developed country in the world, the United States doesn’t have paid family leave. Have a baby in Mexico, get 12 paid weeks off. Move to the U.K., get 18 weeks. In Canada? It’s 35 weeks. Many nations, including Japan, Austria, and Lithuania, offer more than a year of paid parenting leave.

As a result, the strength and well-being of American families relies on a patchwork of inconsistent policies. If you work in New Jersey, Washington State or Washington, D.C., then state law provides for paid family leave. (In N.J., for example, educators can get 85 percent of their pay for 12 weeks, through a benefit funded by payroll taxes.)

In 2019, the Delaware State Education Association convinced legislators to provide 12 weeks of paid parenting leave for state employees specifically. Previously, educators attempted to bank their sick days, or were forced to use unpaid leave provided by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

“Can we afford to have a child? Or even another child? It kind of takes that question off the table,” said DSEA President Stephanie Ingram, in 2019. “This means that our members no longer have to make a choice between the health of their families and their careers.”

Union Power!

In states with collective bargaining, unions can take up the issue at the bargaining table. Thanks to the faculty union at the University of Florida (UF), for example, all UF employees now have eight weeks of paid parenting leave, which can be used by mothers and fathers, after birth or adoption.

The new provision is both big and insufficient, says Hélène Huet, a member of the United Faculty of Florida-UF bargaining team. “Even though it seems to me that [paid family leave] should be a given, it has been a long fight,” she says.

The eight paid weeks is far better than UF’s old system, said Huet, a European Studies librarian. Previously faculty would use the handful of sick or vacation days they had banked, and then “borrow” weeks from future years of employment. By borrowing, faculty could possibly have no leave at all for years after birth or adoption.

But eight weeks still isn’t enough, Huet said.

The union also bargained for eight weeks of paid medical leave so that employees can care for immediate family members with significant health issues. “Again, it’s not perfect, but we’ve gotten messages from people who, for X reason, have had to use the paid medical leave and are so grateful to have access to that.

“It made the fight worth it.”