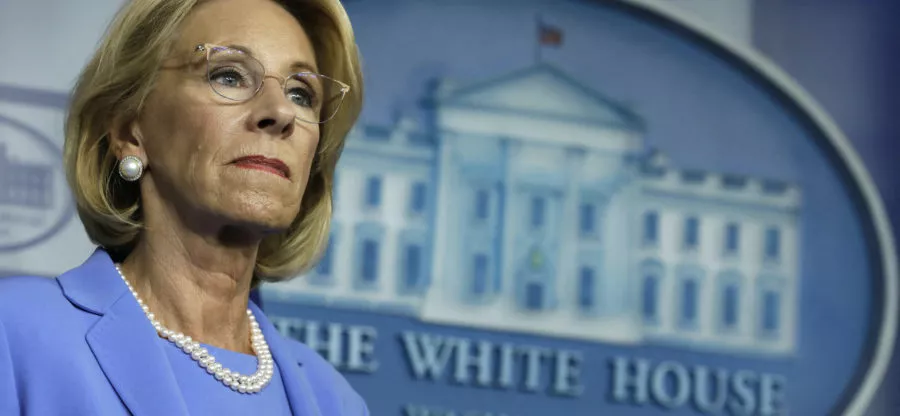

U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos stands during a press briefing on the Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic at the White House on March 27, 2020. (Photo by Yuri Gripas/Abaca/Sipa USA)

For public educators, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a crisis, which they’re tackling through hard work, creativity, and communication with students and families. Educators are streaming lessons, delivering meals, and bridging gaps in technology—with enormous approval from parents.

But for for-profit education businesses and proponents of school privatization, especially Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, the pandemic is something else.

It’s an opportunity, a chance to steer hundreds of millions of dollars in public money away from public schools and students, and into private businesses and corporations. From Washington, D.C., DeVos has created a $180 million voucher program for private and religious schools, using federal coronavirus-relief funds, and has ordered states to redistribute their CARES Act funds to private schools. Two states have refused, and key Republican Senator Lamar Alexander—chair of the Senate's powerful education committee and a former Secretary of Education—has questioned DeVos' attempt to rewrite federal rules intended to support low-income students.

"Am I correct in understanding what your agenda is?" a Catholic leader recently asked DeVos in a radio interview. Is it about "utilizing this particular crisis" to boost private schools? "Absolutely," she said.

Meanwhile, online education companies are like “coke dealers handing out free samples” in districts across the nation, says political economist Gordon Lafer. Their goal? Hooking lawmakers on their products, and winning local and state taxpayer funds that would otherwise go into public schools.

One recent example is a $525,000 contract that Alaska signed this spring with Florida Virtual School, sending hundreds of millions of Alaska taxpayer dollars to Florida and duplicating work already done well by Alaska teachers. The contract came as a shock to Alaska teachers who weren’t consulted by state officials and “who have proved themselves ready to confront and overcome the considerable obstacles of distance learning in America’s largest state,” wrote NEA-Alaska President Tim Parker in the state’s largest newspaper.

In more than a half-dozen other states, educators report new, aggressive marketing campaigns from for-profit, online educational companies that seek to grab a share of dwindling public funds. (As state revenues take a hit from the COVID-19 related shutdown, some school districts are planning for 15 to 25 percent cuts in funding next year.)

“The privatizers are hungry right now,” said Bryan Proffitt, vice president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, to NC Policy Watch. “They’re going to push online education, they’re going to push charters, they’re going push [the narrative] we didn’t need teachers in the first place. They’re going to do all that. They’re already doing it.

“Our side has to be willing to fight back just as hard.”

Students First, Please

In Alaska, even before COVID-19, teachers have known that digital learning is necessary. Often, rural Alaskan students will want a higher-level or specialized class, say multivariable calculus or AP Spanish literature, that isn’t available in their small village school. To accommodate students' needs, teachers will be located in front of a camera hundreds of miles away—although they occasionally will fly to deliver in-person lessons, too.

Online education companies are like “coke dealers handing out free samples." Their goal? Hooking lawmakers on their products, and winning local and state taxpayer funds that would otherwise go into public schools."

This kind of approach to digital learning is consistent with NEA’s policy on digital learning, says Parker, which the NEA Representative Assembly approved in 2013. (Parker would know—he served on the policy committee.) It’s not about replacing teachers with laptops. It’s about enhancing opportunities for students. “You have to put student learning at the center of the discussion. That’s where we have to start,” says Parker.

The Florida Virtual School contract didn’t do that. Those Florida teachers, who are public employees, don’t know Alaska students, Parker points out. They don’t have deep, caring, long-term relationships with students and families like their Alaskan teachers do. “[With Florida Virtual School,] it’s like, ‘read this, do this worksheet, and I’ll video chat with you every other week.’ That doesn’t lead to student learning, and that’s where our objections start,” says Parker.

Alaska educators pushed back in emails and phone calls to the commissioner’s office. “[The commissioner] apologized and he’s still apologizing,” says Parker. “What he says, and I think he’s honest, is that he wishes he had landed on a content-only platform. Everybody needs content. It’s like the New Age version of textbooks. We need content platforms, too—Canvas, Google.”

Meanwhile, the contract with Florida Virtual Schools, which operates like its own school district in Florida and has been mired in mismanagement scandals, doesn’t fix the biggest problem with virtual learning in Alaska—and that’s the fact that half of the massive state doesn’t have broadband access.

Sniffing Out Profit

Florida Virtual School isn’t the only online, education enterprise to see potential profits in the pandemic. NEA members all over the U.S., including in Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota and Tennessee, report seeing and hearing more aggressive advertising on social media, TV and radio for K12 Inc., a scandal-ridden, for-profit company that sells online education to students.

Across the country, K12 Inc. runs about 70 online schools, mostly for-profit charter schools. The company is raking in taxpayer’s money—charter schools rely on public funds to operate—but the return on investment to those taxpayers is awful, researchers have found. Students aren’t learning as much as their peers, researchers at the Center for American Progress (CAP) found. Class sizes are huge. Teachers are poorly paid.

Instead of investing in student success, CAP found that the company spent $11 million on the compensation of its top-five executives in 2017, and nearly $38 million in advertising in 2018. Four years ago, then-California Attorney General Kamala Harris reached a $168.5 settlement with K12 Inc., over false claims and advertising that K12 Inc. made to students about its for-profit, online charter schools in California.

Despite these many issues, the company still has powerful supporters—including Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who once was an investor, Politico reported. And now, the company sees huge opportunity.

In an earnings call with K12 Inc. investors last month, the company’s CEO Nathaniel Davis spoke of the “upside of the pandemic on our business,” the Seattle Times reported. Said Davis: “As I’ve already said, it’s horribly unfortunate for so many people all around the world. But we’re in the business that helps schools and students in situations exactly like this.” Since the pandemic started, K12 Inc’s phones “have been ringing off the hook.”

It Starts at the Top

“Opportunity” is also what Education Secretary Betsy DeVos sees. “This is an opportunity,” she said, in an interview with right-wing radio talk show host Glenn Beck last month, “to collectively look very seriously at the fact that K12 education for too long has been very static and very stuck.”

This mission of hers is not new: DeVos has been promoting the use of public funds for private educational businesses, like for-profit colleges and corporate-run charter schools, since she took office three in a half years ago. For the most part, her agenda has failed. But through Congress’ emergency response to the pandemic, more federal money is available now.

In April, a month into the COVID-19 shutdown, she handed out $200 million to IDEA, a charter school chain that has come under scrutiny for its lavish spending, including the planned $2 million lease of a private jet that it scrapped after public outrage.

Through the CARES Act, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is trying to reroute funds intended for public schools to private schools.

Through the CARES Act, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is trying to reroute funds intended for public schools to private schools.

More recently, she has used $180 million in federal coronavirus-relief funds to start a voucher program for private school students, which she calls “microgrants.” Even worse, she has told school districts that they must take their CARES Act money, which is designated for low-income students, and share it with private schools. And she has directed them to distribute those funds based on a private school’s total enrollment, rather than its number of low-income students. This means that the largest, wealthiest private schools would grab the lion’s share.

This isn't what Congress expected, said Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN), who chairs the Senate health and education committee. In Tennessee, the difference would shift tens of millions of dollars from public to private schools. “My sense was that the money should have been distributed in the same way we distributed Title I money. I think that’s what most of Congress was expecting,” Alexander said.

Two states have refused to comply with DeVos' rewriting of the rules: Maine and Indiana, where the state superintendent is a Republican. In Maine, the DeVos guidance would divert $1.5 million in federal funds to private schools, instead of the $200,000 that the original formula would share.

“It’s shameful that the Trump Administration would use this pandemic to advance their extreme agenda to undermine public education,” said Maine lawmaker Chellie Pingree. “Betsy DeVos can not simply decide to deviate from a formula that has been used for years, especially when it diverts money from public schools.”

NEA leaders agree. “Students, parents and educators are grappling with a global crisis," said NEA President Lily Eskelsen García. "They do not need the ridiculous over-reach of the Education Secretary to do now what she has been unable to do for three and a half years, and that is to create a federal school voucher program that uses public money to support private, often religious schools. Her political agenda is irresponsible and hurtful to students."