Since 1966, the NEA Human and Civil Rights Awards (HCR) have honored individuals and organizations who have advanced human and civil rights and provided educational opportunities for traditionally marginalized groups of students. Sixteen HCR award categories exist; each named after a person who has made a deep impact in his or her community.

These are the inspirational stories of just a few of the awardees. To learn about all of the 2020 winners—the “righteous angels among us,” as former NEA President Lily Eskelsen García called them—visit neahcrawards.org.

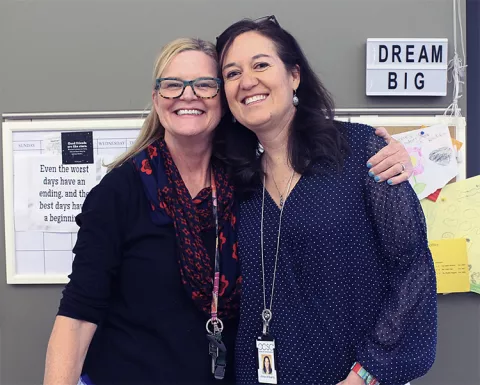

Dreaming Big in Utah

In 2016, Utah teacher Melanie Moffat looked at the students taking Advanced Placement (AP) and other college-level math and English classes at Park City High School—and grimly noted a lack of first- generation Latino students.

Today, what she sees is very different. “We had 17 in AP environmental science last year, 20 take concurrent-enrollment English, which is college level. I have a student who is graduating with 30 college credits this year because of AP,” she says.

The difference? In 2017, Moffat and teacher Anna Martinez Williams created the Dream Big program, a monthlong summer program that prepares first- generation Latino students for success in Park City’s advanced classes by pre-teaching them class vocabulary and concepts.

“Now more than ever, educators have a tremendous responsibility to demand equity within our public schools,” Williams says.

For their efforts—which are breaking down the barriers that block Latino students from success in high- level classes and propelling scores of first-generation students to college—Moffat and Williams earned NEA’s George I. Sánchez Memorial Award.

“Honestly, I feel a little guilty about the award because it’s a group effort,” Moffat said, upon receiving the honor this summer. “If we didn’t have so many dedicated AP English, math, and science teachers working with us, we couldn’t help so many kids.”

Dream Big started with 22 students in its first year. It doubled the following year, and by 2020, the program had grown to 60 students. (Classes still met in person this summer, but were restricted to five students per classroom and were extended for seven weeks because of the pandemic.)

One of the biggest obstacles for first-generation Latino students is the academic vocabulary that AP classes require, says Moffat. Although most Dream Big students have “graduated” from English as a second language classes, they still may lack the specific vocabulary to succeed in, say, AP English language and composition.

During summer classes, specific AP teachers pre-teach the vocabulary necessary in their subject areas and aim to work through the first months of their curriculum. One AP science teacher told Moffat that she sees how that pre- teaching has transformed her classroom. In the first weeks of fall, when she asks questions, her Latino students are the first to raise their hands.

“Before the program, she could see the other students eyeing [their Latino classmates], like ‘I don’t want to be their partners,’” says Moffat. “Now, the other kids are clinging to them.”

In addition to challenging the implicit biases of their peers, the program has changed the way that some first- generation students see themselves. Previously, they may not have envisioned themselves as AP scholars. They never saw students from their background in those classes. But now Moffat and Williams have the data to show them who they really are.

A Bridge Between Generations, Built of Sweet Grass

Wisconsin traditional arts teacher Ben Grignon recently read about the Grand Ronde Indian tribe in the Pacific Northwest, whose tribal motto is, “We’re not raising children, we’re raising elders.”

The words resonated in his heart. A member of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, Grignon knows that the endurance of his culture depends a great deal on his teenage students at Menominee Indian High School. Will they learn their people’s language, or will it die? Can they tell the traditional stories, or will they disappear?

In Grignon’s classroom, students practice and explore Menominee fiber arts, basketry, bead work, leather work, traditional pottery, and more. “I’ve been thinking a lot about how we give [young people] those skills, so that someday they can pass them on to the next generation of Menominee people,” Grignon says.

For this work, Grignon earned NEA’s prestigious Leo Reano Memorial Award. “Sometimes I have that imposter syndrome, where I don’t feel like I deserve something like this,” he says. “But it’s really important for our community, for our students, to see our people getting recognized. And I thank NEA for helping my students to see how important our culture is.”

Grignon sees himself as a partner in his students’ journey from child to elder. His classroom is a peaceful, collaborative space. “I don’t have a desk, so I move from table to table. Once they feel safe and comfortable doing what they’re doing and getting into their work, we can begin to have conversations,” he says.

His classes range from “wood, stone, and bone”— where students examine artifacts of their people and attempt to re-create them—to traditional basketry, where students start off with yarn and transition into more difficult natural fibers, such as pine needles and the Wisconsin prairie’s sweet grass.

Helping students to develop the skills of their people is one of Grignon’s goals. But it’s not the only goal, or the most important goal.

“I want them to understand who they are as human beings, particularly as Menominee people,” he says. “I want them to look at where we come from, at the things our ancestors throughout the years have held on to and wanted to pass on as a Menominee aesthetic—the things we needed to use to survive, and the things we thought were beautiful. My ultimate goal is to connect these kids to their ancestry, to their community and culture.”