Theft is a major offense -- in or out of school -- and students caught stealing usually face suspension or other tough discipline measures. But when a theft occurs in a school that has adopted restorative discipline practices, the outcome looks very different.

Consider this scenario from a Dallas, Texas, middle school.

A mobile phone goes missing during an all-female dance class. The owner of the phone reports the theft to her teacher, saying she suspects it was stolen in the locker room while the girls were changing. The teacher must then report the theft to administrators, but what happens next is what distinguishes restorative discipline from resorting to more severe consequences.

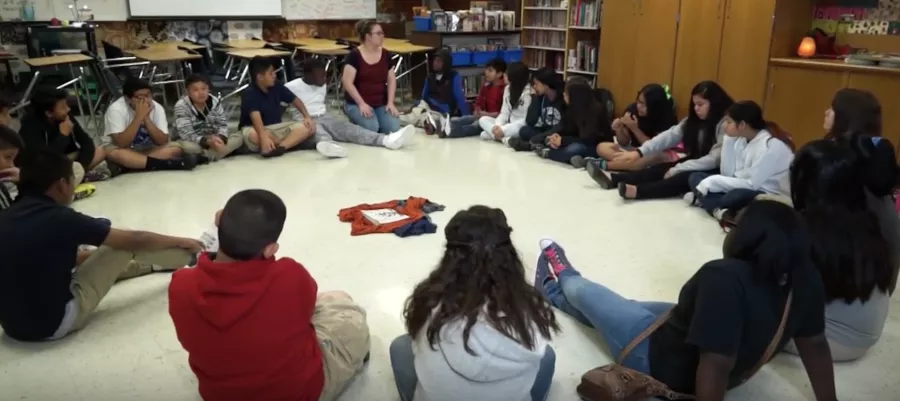

Rather than searching out the suspect, assigning blame, and doling out a punishment, the teacher and an administrator gather all the girls in a circle to discuss what happened. Each girl speaks about how she felt sitting in a circle with a student who would steal from someone in their class. They shared what they’d like to say to that student, and what they thought the consequence should be if that person decided to return the phone.

At the end of the circle discussion, the girl whose phone was stolen was asked if she’d like to add anything. She said she needed the phone because her parents work late and she meets her younger sister after school every day to walk home together. If anything goes wrong, the phone is the only way she has to reach her parents.

The next day, the phone turns up in the principal’s office. No one is suspended or otherwise severely disciplined and the phone is returned to its owner.

This effort has focused on students building relationships with teachers in the hopes that in these relationships, problems can be addressed and solved before they become bigger issues" - David Griffin

“This practice is called ‘classroom circling’ and it’s a key element to restorative practice,” says William Jay Sheets, Restorative Practices Coordinator for the Dallas Independent School District. “The foundation is being proactive in the classroom, investing time into your students and really listening to them.”

Dallas-NEA, the Dallas affiliate of the Texas State Teachers Association, collaborated with Dallas Independent School District to pilot restorative discipline programs in six Dallas elementary and middle schools - Caillet Elementary, Dunbar Learning Center, and Medrano, Gaston, Hood and Boude Storey middle schools. A grant from the National Education Association helped fund teacher training in the practice.

The results speak for themselves: Last year, in-school suspensions at the piloted schools dropped by 70%. Out-of-school suspensions dropped by 77%. The number of students sent to alternative school was cut in half.

“This effort has focused on students building relationships with teachers in the hopes that in these relationships, problems can be addressed and solved before they become bigger issues,” says David Griffin, teacher leader with Dallas ISD and a member of the NEA-Dallas board of directors.

Cutting Off the School-to-Prison Pipeline

Like many urban districts, Dallas has a history of harshly disciplining young black boys much more often than other students. Last year, a report from juvenile justice advocacy group Texas Appleseed showed that black elementary students in the state were more than twice as likely as whites to get out-of-school suspension and that Dallas had one of the highest rates in the state for suspending elementary school students.

Suspending kids – sometimes for minor infractions – has fueled what is known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

School suspension is the number-one predictor— more than poverty—of whether children will drop out of school, have run-ins with the juvenile justice system, and, in adulthood, face unemployment, reliance on social-welfare programs, and imprisonment. (See NEA's policy statement on the school-to-prison pipeline adopted by the 2016 Representative Assembly.)

The idea of restorative discipline, also known as restorative justice in the criminal justice system where it originated — is to change the culture and climate of a school so that students who act out are given a voice and listened to as a way to get to the root of the problem. Kicking kids out of school for problem behavior is a quick, easy response, but it solves nothing and simply breeds more problem behavior.

After researching its effectiveness, Dallas-NEA and Dallas ISD decided to use the restorative practice of classroom circling to get at the heart of discipline problems. It works exactly how it sounds, says Sheets of Dallas ISD. Students sit in a circle with their teacher to address whatever issue has arisen. They each get a turn to speak when the “talking piece” – an object chosen collectively by the class – is passed to them in the circle.

“This takes the anxiety out of the process, so every student knows they’ll have a chance to speak and they know exactly when they will have the floor,” Sheets says.

At Medrano Middle School, there are planned circles at least once every six weeks for relationship building, but more will take place when an issue needs to be addressed. In relationship building circles, kids are asked a variety of questions, about favorite music or movies, for example, or what what they’d like to see changed at school.

Take Action

Sign the petition to shut down the school to prison pipeline!

Dallas Gutierrez, an assistant principal at Medrano, said under the old method, students were sent to in-school suspension or received out-of-school suspension for infractions. Some major incidents, such as having a gun or drugs, still require suspension. But most problems are minor and can be dealt with using restorative discipline, he told the Dallas Morning News.

“Restorative discipline is really building relationships with kids and teaching them this is the way you handle problems,” Gutierrez told The Dallas Morning News. “What you’re really trying to do is get to the root of the problem to solve it.”

Respect Agreements

But before the first circle can take place, the class must draft a “Respect Agreement.” The agreement contains common language between the teacher and students about the definition of respect in class and at school. It defines what respect looks like from student to student, student to teacher, teacher to student, and student to school. The words are created and agreed upon by the teacher and all of the students in the class, so everyone has input and a voice.

When a problem arises, like one student shoving another, the two students and the teacher would have a conflict resolution circle to clear the air. But because it happened in class, the students are accountable to the classroom community and there would be a class-wide circle as well.

“The builds empathy and broadens perspectives,” says Sheets. “But are we all human and will we revert to old ways? Are teachers going to yell at students sometimes? Are kids going to act out sometimes? Absolutely. But the great thing about this is the accountability – respecting each other and the class community is not one person’s rule, it’s everyone’s agreement.”

"Respect Agreements" drafted at Caillet Elementary School in Dallas.

"Respect Agreements" drafted at Caillet Elementary School in Dallas.

Sheets acknowledges that restorative discipline may sound a bit touchy feely, especially to veteran educators who have seen all kinds of incorrigible behaviors. But part of the practice is that it’s voluntary. Nobody has to hold classroom circles if they don’t believe in its effectiveness. However, in the Dallas pilot schools they’ve discovered that the most reluctant have jumped aboard after experiencing the practice first-hand.

Administrator and Educator Staff Circles

The pilot schools in Dallas were chosen based on the administrators’ willingness to participate in restorative practices. For example, an assistant principal in one of the pilot middle schools modeled the practice with the sixth grade staff. They created a respect agreement and agreed upon how they would treat each other and hold each other accountable. Educators could share what they wanted to see in cafeteria dismissal procedures or hallway behaviors, essentially offering their input in how they thought the school should be run.

“The impact is that teachers feel like they are being listened to, and that they have a voice,” Sheets says. “Later in the school year, the educators reluctant to try restorative practices would discover that they benefited from having a voice and they saw how their students would as well. They aren’t forced, but they get to see the impact it has when they are a recipient of the practice.” Still, some were unconvinced -- until they saw the results.

Dallas is expanding the restorative discipline program by four more elementary schools and two more middle schools for the 2016-17 school year.

“And then we’ll be ready to take on the high schools,” Sheets says.

-------------------------------------------------------

To learn more about strategies for keeping kids in the classroom and out of the courtroom, view and download NEA EdJustice: Freeing Schools from the School-to-Prison Pipeline.

Read NEA's Policy Statement on Discipline and the School-to-Prison Pipeline.