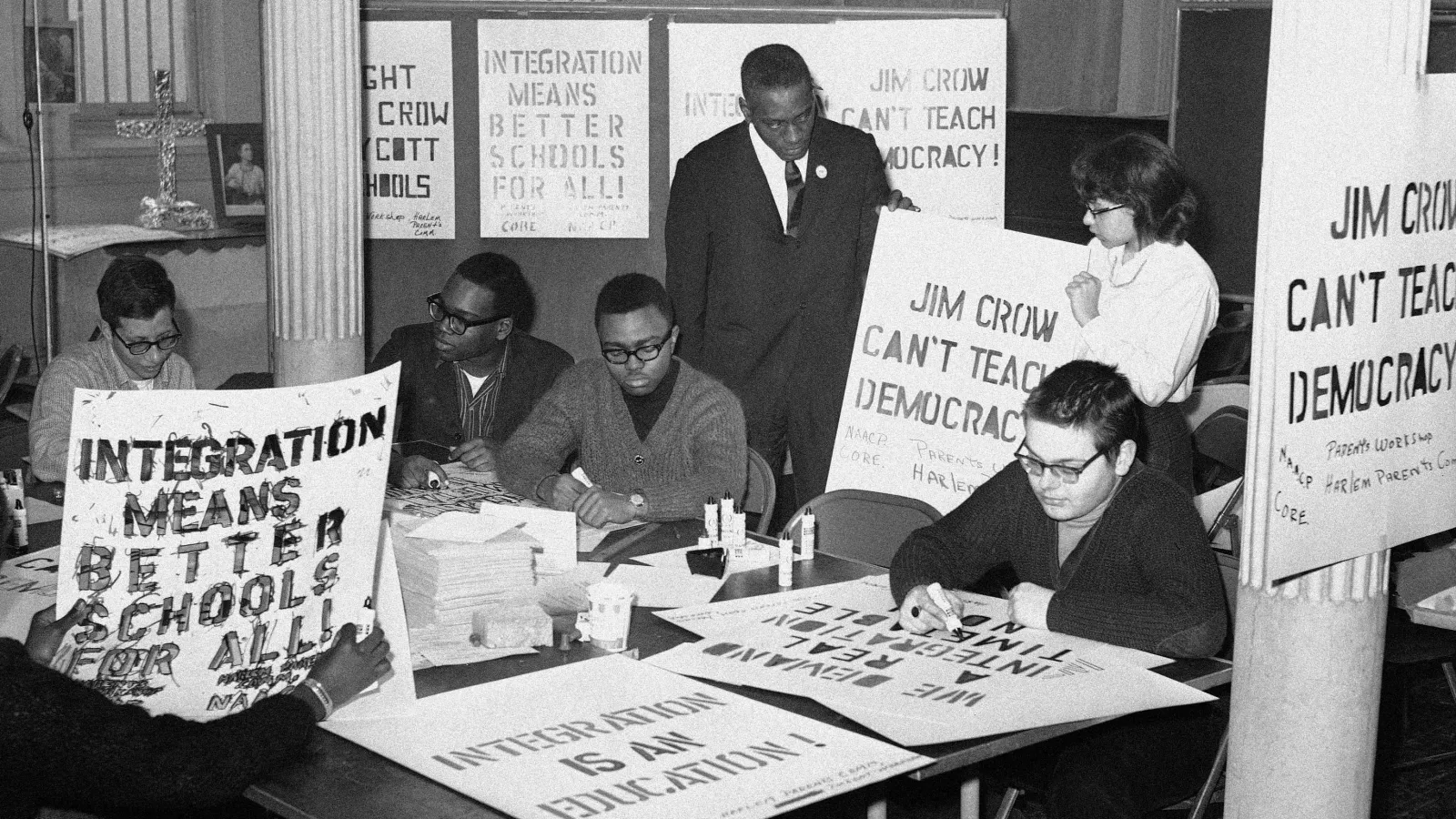

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka landmark Supreme Court decision that ended the legalization of racial segregation in public schools and was a major catalyst for desegregating higher education institutions and housing. The decision, issued on May 17, 1954, also shattered Jim Crow laws and served as the cornerstone of the Civil Rights Movement.

The following decades brought a seesaw of social progress and setbacks. And still today, the promise of Brown—integrated and equitable schools for all students—remains elusive.

Massive resistance to the ruling, especially by white elected officials and community members, has blunted its promise. Today, these voices are growing louder once again.

Extremist conservative groups mischaracterize students—whether they’re Black, brown, or White; Native or newcomer; Asian; LGBTQ+; or people with disabilities—and stoke fears about what’s being taught in schools, from kindergarten through college.

These divisive strategies are being used to ban books, dictate what educators can teach, and block students from learning about people’s shared experiences of confronting injustice.

The road to racial and educational equity may be long, but the collective vision of Brown can still be achieved.

“If vouchers end up allowing some large number of middle-income families to leave the public school system, … what we have left is a public school system in which only poor kids and kids of color go.”

—Derek W. Black, University of South Carolina School of Law

Brown Showed Potential

The rollout of Brown was slow going. The court left implementation up to Southern states, directing them to end segregation with “all deliberate speed.” This essentially translated to no speed at all.

It would take more than a decade for school officials to desegregate schools, but change did take place, says Derek W. Black, a civil rights and constitutional law professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law.

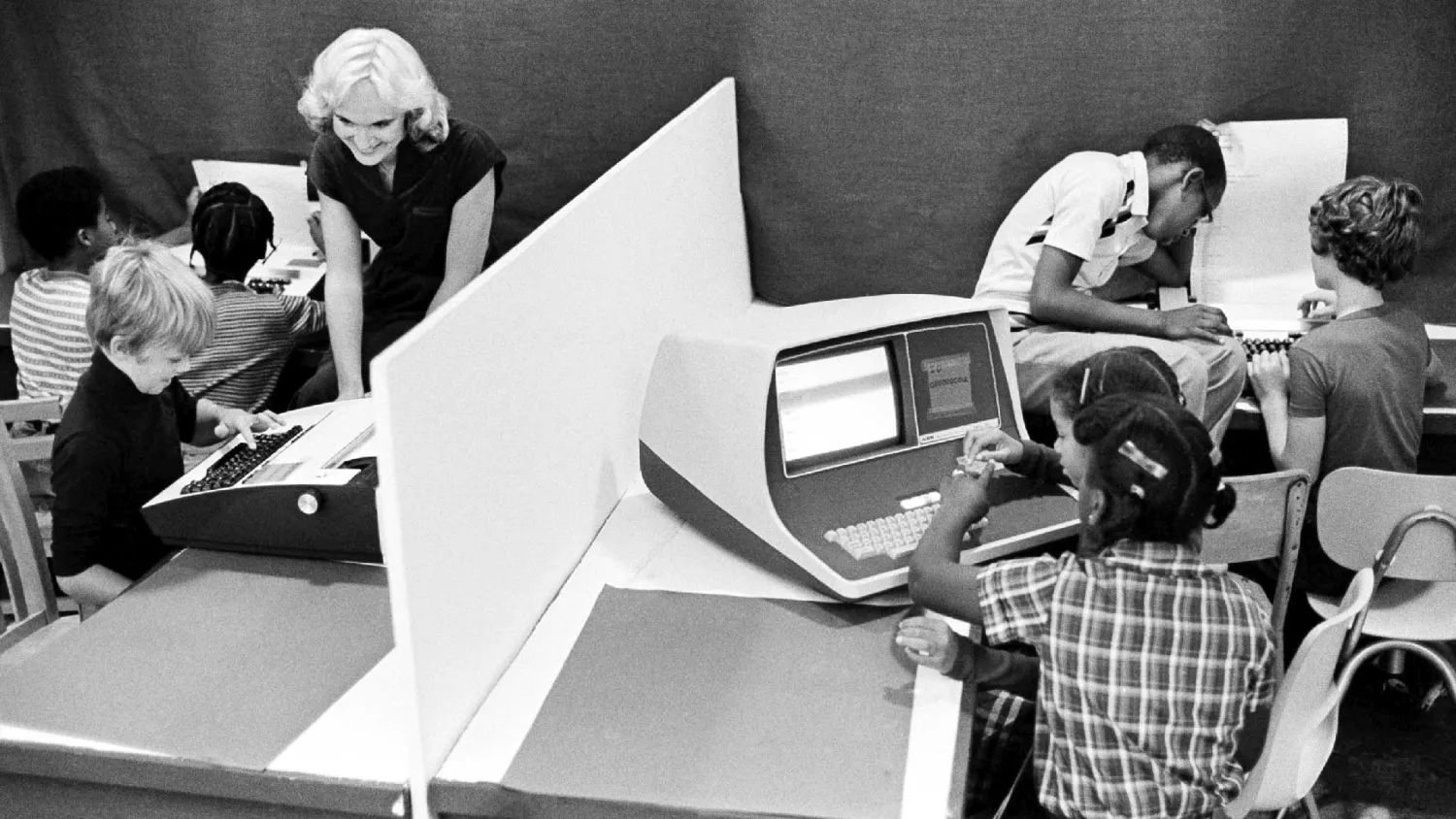

“There was a tremendous amount of progress made between the late sixties and the end of seventies,” he says. Post-decision, he notes, the number of Black students enrolled in desegregated schools in the South went from less than 1 percent to 40 percent.

“When you think about effective education policy and social change, there’s nothing that gets close to [Brown],” he says. “Achievement gaps closed more during that time than any other in history.”

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, academic achievement and high school completion rates among Black students climbed substantially, and the gap between them and White students narrowed sharply, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

But by the 1990s, progress had ground to a halt. Achievement gaps in every grade and subject widened. Today, schools are more segregated than they were in the late 1960s.

“A lot of white supremacists use the same tactics over and over because they’ve proven effective.”

—Janel George, professor, Georgetown Law Center

What Happened?

“It’s not that Brown failed,” Black says. “It’s that we failed to finish the job.”

And by “we,” he means federal officials who withdrew their support from school desegregation efforts.

In a 2022 article by FutureEd, published by Georgetown University, Janel George spells out how the reversal of these students’ progress was an intentional strategy executed at the highest levels of government.

Former “President Nixon nominated Supreme Court justices who pushed back on school desegregation remedies,” writes George, a Georgetown law professor who founded the university’s Racial Equity in Education Law and Policy Clinic.

Former “President Reagan eliminated the Emergency School Aid Act, which had provided federal funding to school districts committed to desegregation,” she continues.

“He eventually eliminated most federal funding for school diversity, leaving only the Magnet Schools Assistance Program intact and undermining progress on diversity.”

The New Massive Resistance

Today’s resistance to desegregation and racial equity looks eerily familiar.

“A lot of white supremacists use the same tactics over and over, because they’ve proven effective,” George says.

In an upcoming paper in the Georgetown Law Journal, she argues that the same tactics lawmakers employed during massive resistance to Brown underlie today’s opposition to diversity, equity, and inclusion. George frames these tactics as deny, defund, and divert:

DENY—During the massive resistance that followed Brown, Black students were literally denied entrance to an integrated education. Today, some lawmakers and school boards are denying curriculum that recognizes this nation’s history of massive resistance, the legacy of racism, and its impact on current inequities.

DEFUND—During the Brown resistance, the goal was to defund integrated schools and deny them state funding. Today, attacks on public education carry state and local provisions that would withdraw funds for teaching “divisive concepts.”

DIVERT—During Brown resistance, Black educators were diverted out of the teaching workforce. An estimated 100,000 Black educators were fired, and many more were displaced. Today, certain lawmakers criminalize educators, who can lose their jobs or face felony charges for teaching topics of race and gender.

The Road to Progress

Undoing policies that drive segregation is a good start toward integration and racial equity. And progress has been made.

In 2021, Congress finally overturned an anti-busing law, enacted in the 1970s, that barred the use of federal funds for transportation used to support school integration.

“For people who want to maintain segregation … it’s more politically palatable to say, ‘I’m opposed to busing’ than to say, ‘I’m opposed to integration,’” George says.

Vouchers Are the New Segregation

Today, the same thinking applies to vouchers. Politicians use these schemes to segregate schools and skirt laws requiring that every student, whether Black, brown, or White, have access to a great public school with equitable opportunities.

“We saw vouchers, in the late sixties and early seventies, as a way … to allow White parents to avoid desegregated schools,” Black says. “Now they are using them to avoid public education altogether.”

Vouchers pose a real threat to the existence of public education. “If vouchers end up allowing some large number of middle-income families to leave the public school system, … what we have left is a public school system in which only poor kids and kids of color go,” he says.

If this were to happen, he adds, “the public education project as we have known it for the last two centuries is over. Full stop.”

Voucher Schemes Blocked Nationwide

NEA continues to beat back voucher schemes across the country, so tax dollars go to schools that are accountable to the public.

- NEA Alaska won a lawsuit against the state, stopping parents of children enrolled in homeschool programs from using public money to pay for their children’s curriculum materials and private and religious school tuition, among other expenses.

- In Tennessee, a voucher program failed in the state legislature after the Tennessee Education Association loudly opposed it.

- The Texas State Teachers Association helped educate enough lawmakers about harmful voucher schemes to repeatedly defeat Gov. Greg Abbott’s universal voucher proposal.

- Illinois recently became the first state to end its voucher program, which was draining up to $75 million of public money from public schools.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The attorneys who litigated on behalf of desegregation in Brown envisioned an all-inclusive approach to integration.

This can also be achieved through a comprehensive approach that includes recruiting more educators of color and ending disciplinary policies that punish Black students more harshly than White students—pushing Black students out of schools.

It is also critical to elect pro-public education candidates who will help stop voucher schemes that take money away from public schools, which 90 percent of students attend.

Educators, unions, and allies must continue to advocate for equality to fulfill Brown's promise.