Key Takeaways

- The national teacher shortage is growing — and dangerously impacts students learning.

- But it is not an impossible situation. States, school districts, and school administrators have the power to make changes that will attract and retain teachers.

- Increasing teacher pay, improving professional development, and fostering learning communities are among the solutions.

Schools across the nation have been struggling for years to fill thousands upon thousands of vacant teaching jobs — and it’s only gotten worse during the pandemic, as many educators opt not to return to classrooms they believe to be dangerous.

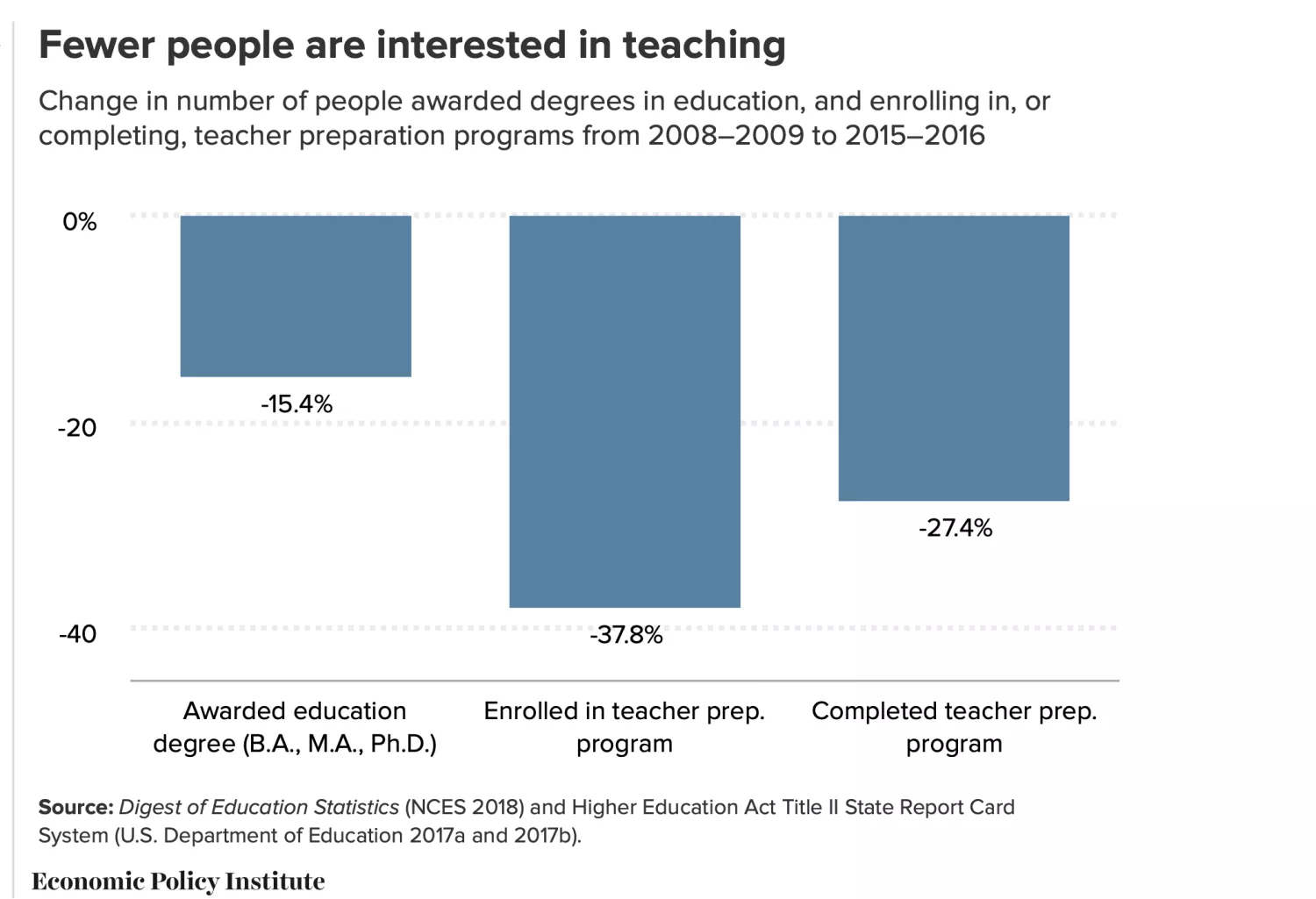

It’s an educational crisis that impedes learning and affects students deeply, especially in high-poverty areas that are more likely to have shortages of highly qualified teachers. But it is not an unsolvable problem — in fact, a recent report from the non-partisan Economic Policy Institute (EPI) outlines approaches for a long-term solution.

“The shortage of teachers is a crisis for the teaching profession, and a serious problem for the entire education system. It harms students, teachers, and the public education system,” said economist Emma García, co-author of EPI’s sixth and last installment in its “Perfect Storm in the Teacher Labor Market” series. “Policymakers must take action to fix the underlying issues — underfunding, poverty and inequality — that have dug us into the deep hole that we’re now in.”

Those specific proposals include:

- Raising teacher pay to attract new teachers and retain experienced ones;

- Elevating teacher voice, and nurturing stronger learning communities where teachers’ influence and sense of belonging is increased;

- Lowering barriers that make it harder for teachers to do their jobs;

- Designing professional supports that strengthen teachers’ sense of purpose, career development, and effectiveness.

There is no simple answer, no magic bullet. The problem is complex, “caused by multiple factors,” and so the solutions also must be comprehensive, the report’s authors warn. They also will require increased investment, or funding, that directly targets teacher pay and working conditions. The bottom line is, these proposals from EPI would treat teachers like the well-educated, highly qualified, “true professionals” they are.

Teacher Pay

Back in August, Arizona started the school year with more than 6,100 vacant teacher positions. Since then, more than half have been filled by teachers who do not meet the state’s certification standards, while 1,728 were still unfilled last month, the Arizona School Personnel Administrators Association found.

Meanwhile, according to NEA data, Arizona’s average teacher salary of $48,723 ranks 47th in the nation.

Florida has similar issues. In Palm Beach County alone, more than 1,000 teachers are staffing vacancies in areas that they’re not qualified to teach. Meanwhile, Florida’s average teacher salary — $48,526 — ranks 48th in the nation.

Teachers often have master’s degrees, even doctorate degrees, and yet they earn far less than other college graduates. This problem, commonly called the “teacher pay penalty,” has grown far worse over the past three decades, EPI has found. Currently, teachers earn about 20 percent less, on average, than their non-teacher college graduates.

With this kind of pay — coupled with the student debt that many teachers must take on to pay for their advanced degrees — a career in teaching doesn’t pay the bills for a middle-class life. As a result, 59 percent of teachers took on second or third jobs in 2016, EPI found.

These financial issues are the chief reason that parents say they don’t want their children to be teachers, according to surveys, and why college students say they’re not going into education. “No matter what she decides, she’s not going to be a teacher!” said California teacher Shdari Crane, of her college-student daughter, to NEA Today last year. After nearly 20 years of teaching, Crane still owes more than $100,000 on her student loans.

“If I would have been a doctor, or whatever, I would have been able to pay off these loans. As a teacher, there’s just no way,” she said.

With this in mind, EPI’s experts suggest teacher pay be increased, especially in high-poverty schools; that pension funds for teachers be adequately funded; and that other programs that help with future teachers’ financial burdens be considered. (For example, NEA strongly supports the expansion of the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, and has a new tool for members to help find the right income-based repayment and forgiveness programs.

Teacher Voice

“As a society we claim—and policymakers often grant—that teachers are professionals, but the ways we treat them indicate otherwise,” the report’s authors write. “Generally, professionals’ voices are central in key decisions regarding how they do their work, the kinds of supports they need to do it well, or their interactions and relationships with peers and supervisors… [And yet], none of these is true with respect to teachers.”

This lack of voice contributes to the teacher shortage. When EPI compared teachers who stayed in their classrooms versus those who left, they found that the group who left were more likely to say they lacked influence over school policy or what takes place in their classrooms. They also said there was less cooperation among teachers.

"It’s an educational crisis that impedes learning and affects students deeply, especially in high-poverty areas that are more likely to have shortages of highly qualified teachers. But it is not an unsolvable problem.""

To address this issue, EPI makes two key recommendations. First, teacher autonomy must be increased. Just 9 percent of teachers say they have a role in discipline policies; just 11 percent have a role in their own professional development. Meanwhile, EPI found that teachers who say they have a say in school policy and classroom activities are more likely to stay in the profession.

With this in mind, teachers “must have a say in the components of teaching that they’re trained to master,” including the curriculum they teach, the classroom practices they follow, the teaching materials they use, as well as their own professional development, the study’s authors recommend. “Top-down policies that ignore teacher expertise, misguided accountability policies that make teachers feel disrespected, and lack of attention to what teachers have to say about the policies in their schools and classrooms are critical obstacles.”

The second recommendation in this area is to nurture stronger learning communities that acknowledge and foster teacher collaboration. Only 38 percent of teachers say there is a cooperative effort among teachers at their schools, but a teacher’s measure of cooperation and support is one of the strongest predicators of teacher retention.

School districts should pay attention to this, EPI says, and ensure through school and district policies and procedures that teachers have time to collaborate, cooperate, observe each other, and provide feedback. (For example, check out this innovative, union-led teacher-mentor program in Florida’s Brevard County that has enabled new teachers to observe the classrooms of more experienced colleagues, and vice versa.)

Lowering Barriers

Poverty, segregation and inequality are huge issues, deeply embedded in American societies, and manifested in classrooms. Students come to school unprepared to learn, hungry or sick; parents have life circumstances that make it difficult for them to engage in their children’s learning; teachers’ safety and mental health is threatened.

In fact, more than one in five teachers report they have been threatened and one in eight say they have been physically attacked by a student at their current school. These difficult school climates contribute to teachers walking away.

But again, there are possible solutions, which EPI suggests. First, hire the right people. Teachers can’t also be first responders, social workers, doctors, and nurses. School districts must hire people who can provide the right interventions, including counselors, nurses, librarians, and paraprofessionals, who can help make schools healthier places, reduce behavioral issues, and meaningfully engage with parents. All educators also would benefit from trauma-informed practices and restorative practices. (Check out NEA’s micro-credential for educators in restorative practices.)

Second, schools and districts must revisit disciplinary practices. Shifting from zero-tolerance policies to restorative practices will result in long-term improvements to school culture. (For example, read how educators at Denver’s Dora Moore School have built a more supportive classroom.)

Professional Supports

Finally, in its fourth recommendation to stem the teacher shortage, EPI’s researchers point to designing professional supports that strengthen teachers’ sense of purpose, career development, and effectiveness.

Only about half of teachers have released time from teaching to participate in professional development, a practice that is common among other professionals in various careers (law, medicine, higher education, etc.) Less than a third are reimbursed for conference or workshop fees, another common professional practice.

Moreover, they have limited access to the kind of professional development that would be helpful. Barely one in 10 say they have influence in determining the content of their own professional development programs.

With this in mind, EPI recommends: first, that teachers have access to “coherent, high-quality, lifelong systems of supports, and that they are engaged in designing those systems.” Teacher residency programs are helpful, as are mentoring and induction programs. Second, teachers should be provided with the option of meaningful “second jobs,” such as mentoring or coaching other teachers, teaching evening classes, or leading induction programs.