Key Takeaways

- $1.5 TRILLION: The total amount of funds distributed based on census data, including money for programs that help students.

- 30%: The expected increase in the number of jobs requiring knowledge of statistics over the next 12 years. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Statistics

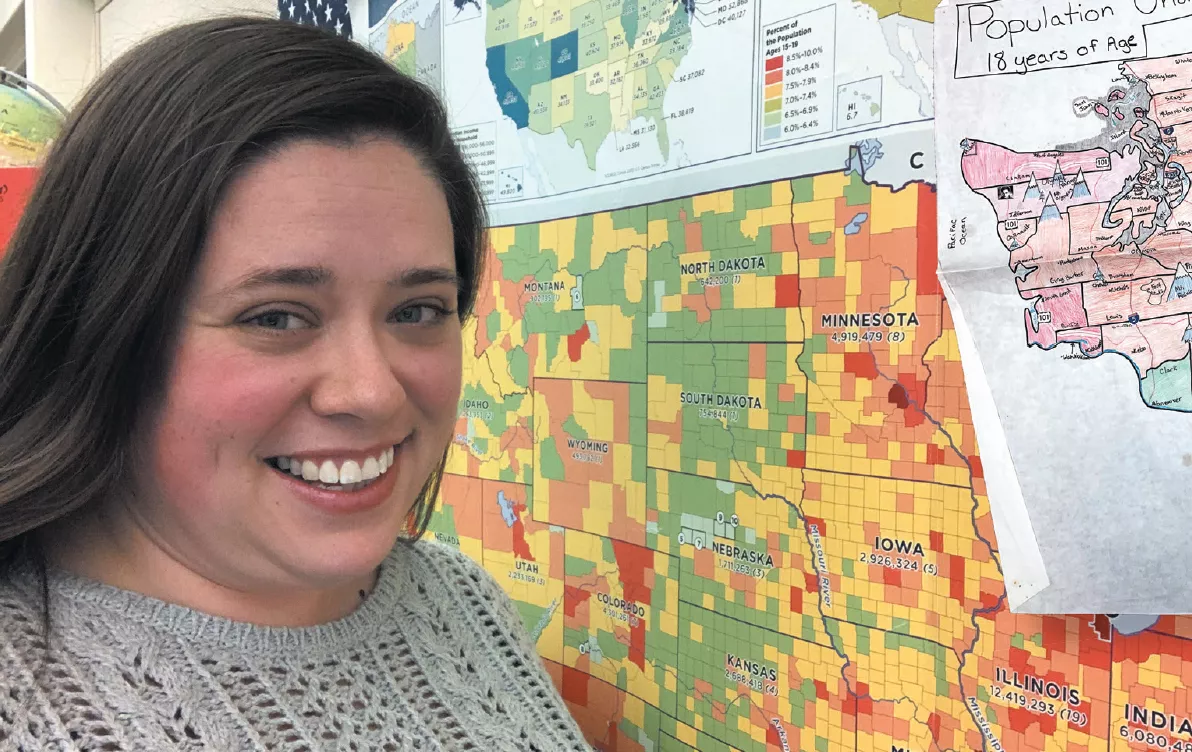

When Kyla Thompson first started teaching language arts and social studies in 2006, one of the things she inherited from her predecessor was a map from the 2000 U.S. Census. “Having nothing else to put up yet, I hung it on my wall,” recalls Thompson, who works at Finn Hill Middle School in Kirkland, Wash.

She also received a great project idea in which students create their own historical maps using census data. “I have done this project in different iterations for the last 14 years, and it’s amazing to see them incorporate layers of information,” Thompson says. Most use 1790 census information, because their focus is early America, she explains.

Thompson also conducts a mock Constitutional Convention, where students learn the history behind the census: Once used by British monarchs to tax their people and conscript youth into military service, America’s founders transformed it into a tool that empowers citizens under the U.S. Constitution.

Educators nationwide have found ways to teach through the census. Students learn about our system of government and the array of critical decisions that are based on census data. They also learn to use statistical information from the census to draw their own conclusions.

This experience should be a part of every student’s education, says Pamela Rawson, a mathematics and computer science teacher at Baxter Academy for Technology and Science in Portland, Maine.

“We should be using statistics as part of a foundation of learning, not an AP course add-on for those students who have time or space in their schedules,” she says.

The more students know about the census and all the information it holds, the more Rawson believes they will “dig deeper into a data set that is interesting to them...to help answer their own questions about their world.”

Lesson plans for all ages

Rawson is one of dozens of educators who write lesson plans offered through Statistics in Schools (SIS), a program developed by the U.S. Census Bureau. The youngest primary learners can use census data to find out how many zoos are in their state, or they can sing the

“Everyone Counts” census song: “The census counts people in homes big and small, you count if you’re tiny, you count if you’re tall...Everyone counts in the U.S. of A., everyone counts in their own special way.”

A more complex lesson tailored to high school students asks them to use past data to predict population changes and then reallocate seats in the U.S. House of Representatives based on their predictions.

Learning to be engaged citizens

Lem Wheeles, a U.S. history and government teacher at Dimond High School in Anchorage, Alaska, also served as an educator-advisor to SIS, providing feedback on lessons in the subject areas he teaches.

Wheeles says that lessons rooted in the census allow students to dive into one of the nation’s best data sets and also emphasize just how important that census is. “First we talk about how federal funding is divvied up among states based on census population fi gures,” Wheeles says. “And then we talk about how it determines representation in Congress and electoral votes.”

Soon, students are looking at their own state and why a sparsely populated northern congressional district stretches across the entire top third of the state, while their own district is just a fi ve-minute drive from end to end. They also wonder how census takers will ever complete the awesome task before them, he says.

“One student said, ‘My dad’s not going to talk to anyone from the government,’ but I pointed out to him: ‘You’re 18, you can respond on behalf of your family,’” says Wheeles. The student agreed that he would.

Teaching through the census can help impart another critical lesson as well. “We’re living in a time when people think they can say ‘fake news,’ in order to ignore ideas they don’t want to hear, even if those ideas are backed up by evidence,” says Thompson. “Trying to get kids to look at sources critically—that’s my goal.”