Key Takeaways

- As the 50th anniversary of the Evergreen strike approaches, the story of these educators still exemplifies the union value of solidarity.

- They stood together, they persisted, and they won the first collectively bargained contract in their district, which included important provisions to improving student achievement.

In spring 1973, three young teachers in Washington’s Evergreen Education Association (EEA) spent nearly two months in jail. Their crime? Leading what a local judge called an “insurrection” of K–12 educators but was actually a pioneering, two-week teachers’ strike, which led to the union’s first collectively bargained contract.

“It was pretty amazing,” says Steve Kink, the Washington Education Association (WEA) field organizer who helped run the strike. “We had this unique group of teachers who simply said, ‘We’ve had enough.’”

The issues? Low pay, class sizes reaching 41 students, and a superintendent who didn’t respect or listen to teachers. The 300 EEA members understood that a collectively bargained contract would make a real difference.

Today, the story of the 1973 strike, and its proof of the power of solidarity, continues to inspire. A scholarship—named for the EEA Vice President at the time, John Zavodsky—honors the legacy of these leaders and is awarded each year to a graduating senior who “speaks truth to power,” says EEA President Kristie Peak.

This is a story of solidarity.

Sunday, May 13, 1973:

With contract bargaining going nowhere, Evergreen educators meet on Mother’s Day night. By secret ballot, they vote overwhelmingly to strike the next day.

Monday, May 14:

Pickets begin.

Wednesday, May 16:

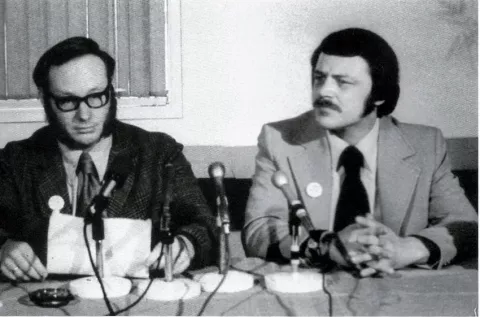

Shortly after noon, a local judge signs an injunction, banning pickets and ordering Evergreen teachers back to work. That afternoon, EEA President Fred Ensman tells his members to “respectfully ignore the temporary restraining order and remain on the picket line … until negotiations have been completed.”

Meanwhile, Evergreen teachers run an ad in the local paper, The Columbian, explaining to the community why they’re striking. It says, in part: “Evergreen teachers are on strike because … they can’t teach effectively with 41 students in the classroom. They need planning time to provide quality instruction.”

Thursday, May 17:

Judge J. Guthrie Langsdorf orders Ensman and EEA crisis coordinator Dick Johnson to appear in his courtroom, where he tells them to send their colleagues back to work. “Fred Ensman told the judge, very respectfully: ‘We’re staying out until we get an agreement.’ So he threw them in jail!” recalls Kink.

In Class Wars—a book about WEA, written by Kink and former WEA official John Cahill—Johnson recalls how he and Ensman were sent to separate jails: “[The judge] flipped a coin, and I was sent to the one with the murderers and child molesters!”

Monday, May 21:

With the strike entering its second week, in defiance of the injunction, the judge summons Zavodsky. Same thing: Send your colleagues back to work. Zavodsky confirms that they’re staying on the picket line until they get a collectively bargained contract. Zavodsky is taken away and put in a jail cell.

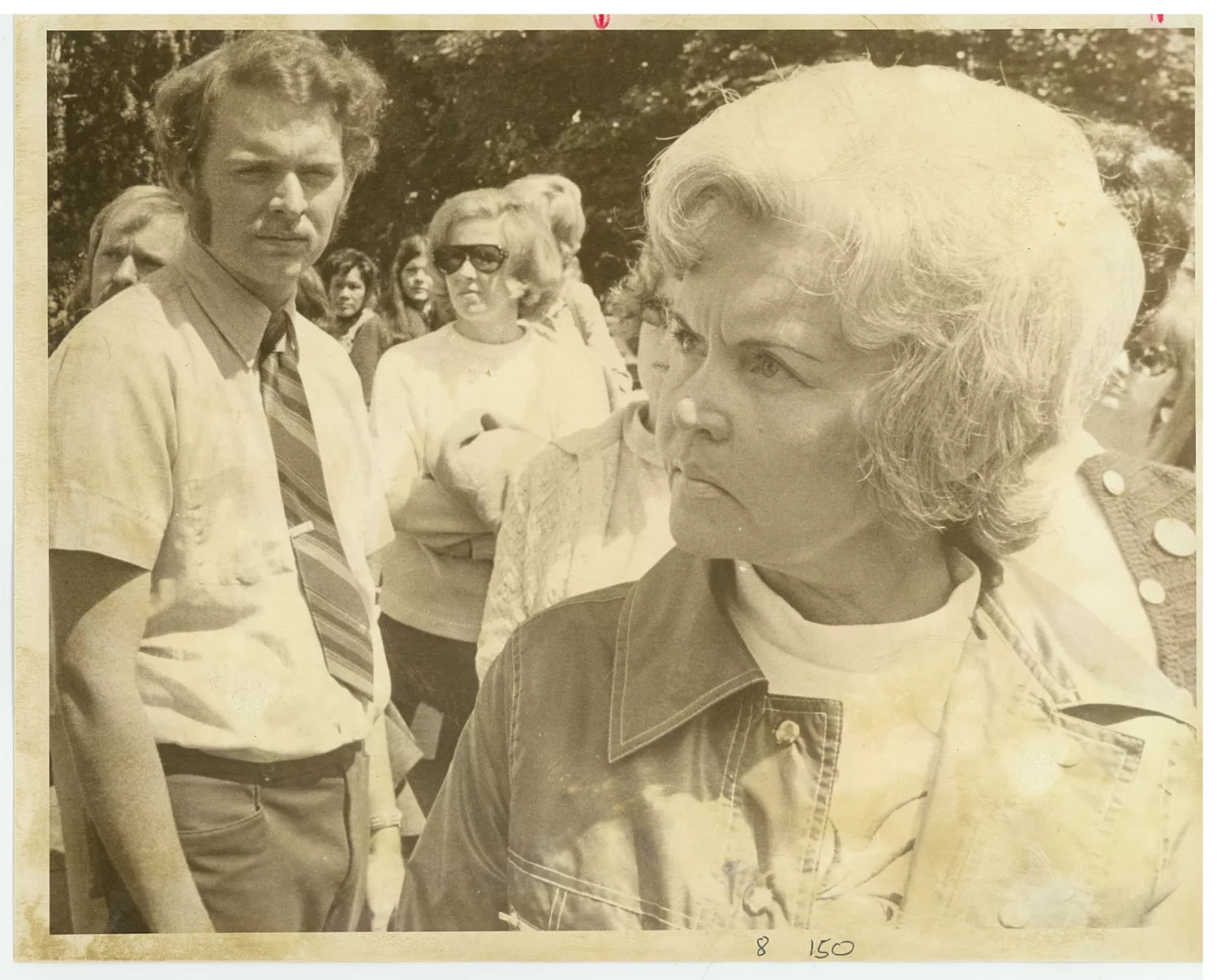

That afternoon, the two WEA organizers, Kink and then-UniServ Director John Chase, tap an “interim president,” an elderly kindergarten teacher named Betty Colwell who is beloved throughout Evergreen. Colwell goes to the school board meeting that night and, Kink recalls: “She told the board, ‘In all my life, I’ve never had so much as a traffic ticket, but I’m telling you, right here and now, I’m prepared to go to jail tomorrow—and it’s your fault.’” Under growing stress, one of the board members begins to cry.

That night, Kink and Chase meet with Evergreen members. “I told everyone, ‘We’ve got three leaders in jail, Betty’s next, and we’ve heard from good sources that sheriff’s deputies are preparing to arrest picket captains,’” Kink says. “One person out of the 300 stands up and says, ‘They may as well take me, too.’ And then everybody starts chiming in, ‘Yeah!’ Let’s go!’”

Tuesday, May 22:

Colwell doesn’t come to the courtroom alone. She’s joined by 300 Evergreen teachers, each carrying a plastic bag with a pair of underwear and a toothbrush.

“The judge says, ‘What do they all have in their bags?’” recalls Kink. “And our attorney tells him, ‘It’s their underwear and toothbrush. They’re here to surrender.” Eleven jail cells are available. Stymied, the judge calls in school board members instead. He orders them to bargain in good faith—or they’d be going to jail. That evening, a federal mediator joins negotiations.

Friday, May 25:

Ensman and Zavodsky appear in Langsdorf’s courtroom again. Zavodsky, who had nine children at the time, tells reporters that he hasn’t lost faith. Both say they’re getting along well with other prisoners who are curious about why the teachers are being held.

“I let the other guys read my mail because they don’t get much,” Zavodsky says.

Meanwhile, a letter appears in The Columbian from a concerned non-educator. “How long must these teachers sit in jail, and how many do we have to put in jail before the school board realizes these are sincere people trying to do something constructive?” he writes.

Tuesday, May 29:

Teachers return to work, as an agreement is reached. It includes key victories around smaller class sizes, more specialists, and planning time for teachers.

The following weeks and months:

Langsdorf lets the three union leaders out of jail to finish the school year, but he demanded an apology and an admission that “they were wrong,” Class Wars reported.

When the leaders refused, he put them back in jail to continue serving their 90-day sentences. While they sat in jail, allowed only one 10-minute visit a week, their colleagues mowed their lawns and repaired their homes.

In a 2015 interview, a modest Zavodsky said it was almost harder for the jailers than him—some of them were former students who knew their prisoners weren’t criminals. But they were forced to uphold the judge’s orders. At the end of June, Evergreen’s superintendent retired. The new superintendent pleaded for the educators’ release, and eventually the judge yielded.

Johnson and Ensman had spent 45 days in jail, and Zavodsky 43.