Key Takeaways

- The opioid crisis' effects on students is far-reaching: teachers, counselors, nurses, and administrators face physical, cognitive, and emotional needs they don’t always know how to meet.

- Given the shortage of mental health supports in the community and the difficulty many families have accessing those services, schools are the best place to provide all the supports children need.

- Despite their own second-hand trauma, educators' first priorities are their students.

Here’s what we know about the opioid crisis: It is the most widespread and deadly drug epidemic this country has ever known. Since 2000, it has claimed more than 300,000 Americans, and deaths continue to rise among men and women of all races, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Last year, nearly 200 American lives were lost every day to drug overdose, and at least two-thirds of those were linked to opioids. Most who die are between the ages of 25 and 44, and many of them have children.

The crisis has pushed the number of incarcerated moms to an all-time high.

We have far less concrete information about the epidemic’s effects on kids—those who were born addicted to opioids, those who have lost parents to overdose or incarceration, or those who are growing up with family members in the grips of addiction.

This fall, NEA Today spoke with 10 educators from two of the hardest hit and longest-suffering states on the opiate map—West Virginia and Ohio—where teachers, counselors, nurses, and administrators face physical, cognitive, and emotional needs they don’t always know how to meet.

There is the kindergartner who becomes so violent, he can hurt adults. There is the second-grade boy being raised by his great-grandmother, who announced excitedly during class that his baby sister—“you know, the one that’s hooked on drugs from my mommy’s belly”—was to be released from the hospital. There are the hungry and the unwashed and the silent children. There’s the third grader who sometimes shows up at school still in her pajamas. She is a foster child, who puts herself on the bus. Another in her grade found both of her parents overdosed in their car (they survived). There are elementary students and middle schoolers who feed and bathe and diaper younger siblings when there isn’t an adult around who is capable of doing it. Tweens are cutting themselves, and teens are caught dipping into the drugs that have surrounded them for so long.

“Some days learning the ABCs and 123s is not what is most important for that student,” says Julie Sturgill, a third-grade teacher in the Dawson-Bryant School District in the Appalachian foothills of southeastern Ohio. Some days, she says, are more about survival. She has washed stinky coats, texted with colleagues at all hours about a student in crisis, and recently allowed an exhausted child to sleep during class. “I never imagined helping to meet such basic needs would be such a big part of my job.”

How Did We Get Here?

A Brief Timeline of America’s Opioid Crisis

Opioids Take Hold

Number of Deaths Begin to Rise

The Prescriptions Keep Coming

A Grim Milestone

Synthetics Enter the Scene

Trump Declares Emergency

Congress Passes Opioid Legislation

‘We Take Them As They Are’

Educators here, as in all public schools, must attend to state standards and the next big test. But they must also keep track of which parents have restraining orders against them and when students need to be released to make their counseling appointments. They keep an eye out for hungry kids so they can slip extra snacks into their backpacks.

Both Jackson County, W.Va., and Lawrence County, Ohio, have faltered and rallied as industries have come and gone. Their once-proud downtowns and neighborhoods are riddled with structures half-fallen, boarded up, or piled with debris.

But their schools are inviting and colorful, filled with student photos and projects, marking their school as a place where each and every one of them belongs.

“Our kids don’t come with a label that says, ‘My mom is an addict,’ or ‘My dad just got out of prison,’ or ‘My family is going through the recovery process,’” Sturgill says calmly. “We just take them as they are and try to figure out what’s best for them.”

There is no part of Julie Sturgill’s life that is untouched by addiction. She has lived the nightmare of seeing her own daughter become addicted to drugs. Now, she is raising her granddaughter.

Madison, who has white blond hair and a whisper of a voice, was exposed to drugs before she was born. Sturgill says her daughter worked hard to get clean, but has since relapsed, so for the past two years, Madison has lived with Julie and her husband, Rick. They are now Madison’s legal guardians.

After a day in the classroom facing more challenging behaviors among 8- and 9-year-olds than she’s ever known in her 20 years of teaching, Sturgill runs a book club as part of a new grant-funded aftercare program for at-risk kids. Not all of those children have families struggling with addiction, but many of them do.

Some evenings and every weekend, Sturgill can be found at church where she and her husband are growing a ministry designed to help people in treatment or long-term recovery and their supporters build a community. Pastor Rick, as his congregants call him, lost his own son to heroin addiction years ago.

As much as her own family has suffered, Julie Sturgill says she is lucky.

“I can do this homework with my granddaughter, I have the ideal schedule, I have the financial means, whereas many grandparents don’t have good health and might be living on very limited means in retirement,” she says.

Every educator we spoke with said that the growing number of children being raised by someone other than their parents is one of the most obvious shifts among their students.

Across the country, 2.6 million children are being raised by family members who are not their birth parents. These “grandfamilies” are most often formed outside of the foster care system, which leaves grandparents or other adult kin to figure out how to nurture children who may be shouldering multiple adverse childhood experiences. Decades of research shows that chronic stress can disrupt neurodevelopment in children and lead to negative coping mechanisms—substance abuse, risky behaviors, and self-harm—in adolescence.

Given the shortage of mental health supports in the community and the difficulty many families have accessing those services, schools are the best place to provide all the supports these children need. But years of insufficient funding have undercut schools’ ability to respond when crisis hits.

So educators do the best they can every day, with every student, even when it comes at a personal cost.

What Educators Are Seeing

‘I Just Want to Fix Them’

Traci Musick, an English teacher at Dawson-Bryant High School in Lawrence County, Ohio, has a recurring dream in which she is trying to tape her broken students back together. It began after she invited her students to journal about their own lives.

One wrote that he was adopted because his parents, both of whom were addicted to drugs, just couldn’t take care of him and his brother. Another student chronicled how she and her mother, who also had substance abuse problems, stayed in different places all over the county, and sometimes her mother’s boyfriends made unwanted advances.

“I quit the journals for a while because it got to be too much,” says Musick. “I get too emotionally invested—I just want to fix them.” As a mandatory reporter, she also found herself talking to the principal several times a week.

But they realized how much students needed to tell their stories, and her principal encouraged her to bring the journal writing back. She did, and added reading assignments by authors who have achieved in spite of the physical and emotional damage caused by their parents’ alcohol and drug abuse.

“Our staff is just phenomenal when it comes to building those caring relationships when something is going on with one of our kids,” says Audra Deere, who taught business and accounting for over 20 years before becoming Dawson-Bryant’s director of student services a few years ago.

She recently attended a training on trauma-informed care that she wishes every educator in their region could attend.

“It spelled out in plain English the reasons for some of the behaviors we’re seeing,” said Deere. That youngster who keeps breaking the rules by putting up the hood of his hoodie might seem defiant, but maybe it’s a small comfort that makes him feel safer, she explained.

‘This Has to be Their Happy Place’

Educators here are acutely aware that any child in their classroom, whether they are from a poor or well-off family, might be processing a hidden trauma, and they strive to make them feel safe at school. But few of these educators had the benefit of any formal training in trauma-informed care.

Nearby Rock Hill School District, which is more rural and has more families in poverty, has received an NEA grant to start a trauma-sensitive school. Several educators will attend the National Conference for Creating Trauma Sensitive Schools in February to kick off the process.

Guidance counselor Bridgette Malone says some of the ways Rock Hill High School has changed since she graduated here just over a decade ago are chilling.

“By the time they’re in high school, the kids think it’s normal—drug use and overdoses and people in your family getting arrested. Like that’s just something that happens,” she says. Malone works with many teens who are at greater risk of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse having grown up with adults using drugs. Starting this year, Rock Hill students with substance abuse problems will have access to a drug counselor if they request help.

That’s a good thing, of course, but educators know the best way to break the cycle of drug abuse is to address students’ physical and mental health needs far earlier.

And that is going to take a renewed investment in our public schools.

In a rare bipartisan moment, Congress passed a major package of opioid legislation in October that, with input from NEA, establishes grants to implement evidence-based, trauma-informed care in areas hit hard by the opioid crisis.

But it could take years for those supports to materialize. In the meantime, educators will stock clothing closets, stuff backpacks with food for the weekend, and, if necessary, set aside instruction to respond to student needs in the moment. Whatever it takes to make students feel safe and loved.

“I don’t let my kids come into the classroom without a smile, and I hug them as they leave,” says Julie Sturgill. “This has to be their happy place, because for some of them it’s the happiest place they have in their lives right now.”

Losing Sleep

On a recent fall afternoon, after more than 600 students had cleared out for the day, Ripley Elementary School in Ripley, West Virginia, was a tranquil place. Aerators bubbled softly in a row of fish tanks. In one of several charming murals lining a main hallway, turtles and schools of fish swam across a gentle underwater scene.

Days are rarely so peaceful for the educators who work in Ripley, a town of 3,000 whose families are breaking down in large part due to drug addiction. Like many communities hit by the opioid crisis, Ripley relies on its public schools to serve as a safety net for its kids.

Signs of the town’s downward spiral are everywhere: Flyers posted along Main Street ask for volunteers to serve as court advocates for local children. An electric sign along the main road asks citizens to become foster parents, while the rate of child removals in the county explodes.

The signs of wear and tear on the educators who help these children every day don’t show on the surface. But when they talk about “their kids,” they choke up a little. They have to pause and take a breath.

“Sometimes you wake up at 3 a.m. and you can’t sleep because a student’s situation is on your mind,” says fourth-grade teacher Mike Knopp, who has been in the classroom for 15 years. “It scares me to think how they could end up. I’ve seen my former students in the obituaries, or found out on Facebook that we lost one to drugs or suicide…it hurts.”

Educators here say more children each year are racking up adverse childhood experiences, stressful and traumatic events that include abuse, neglect, and witnessing the worst—like mommy and daddy being taken away late at night in a police car or an ambulance.

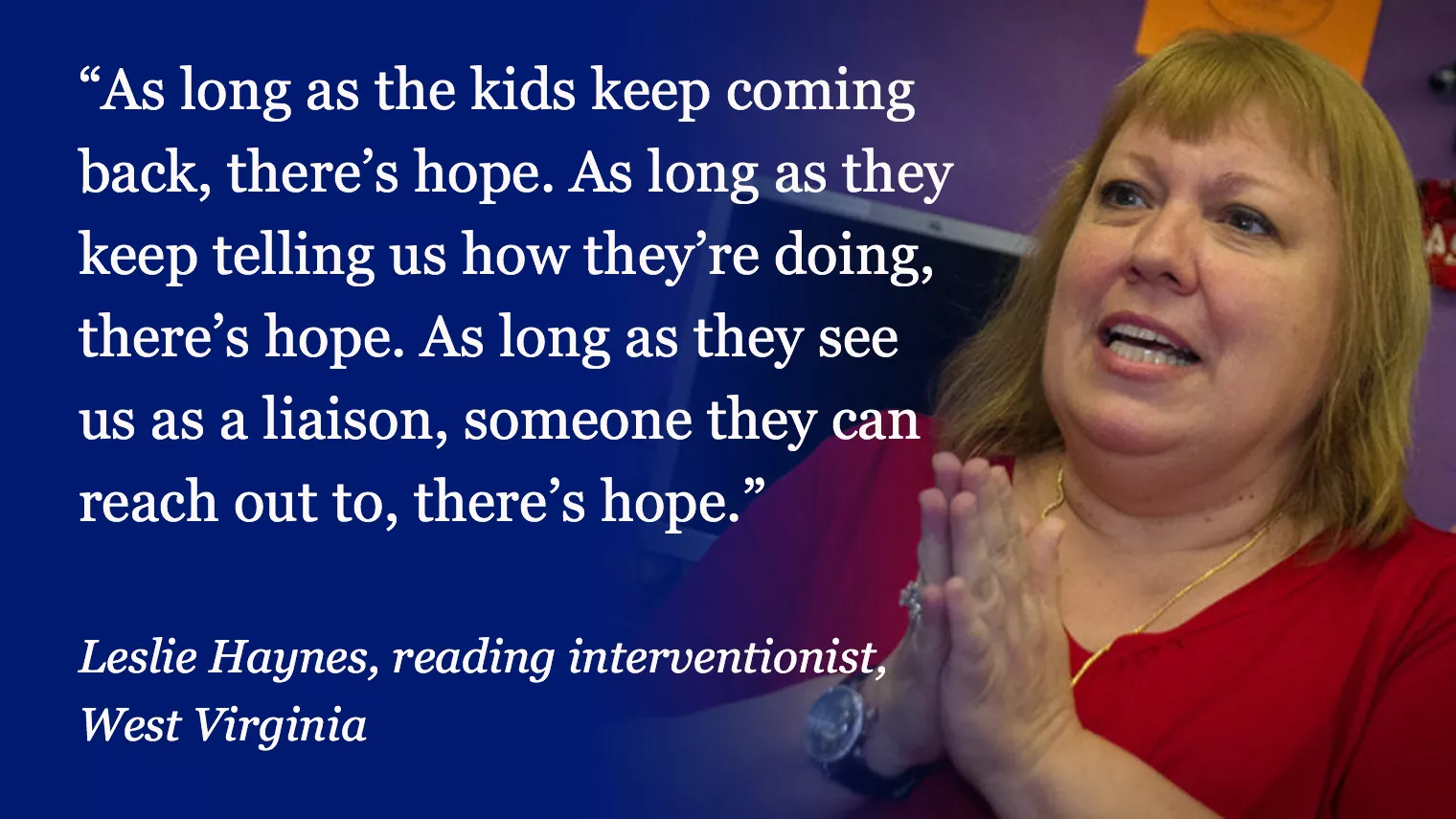

The three teachers we spoke with in Ripley—Knopp, second-grade teacher Lori Mahan, and Title I Reading Interventionist Dr. Leslie Haynes—who have more than 75 years of classroom experience between them, shared with us the questions that they lose sleep over: Why aren’t their teaching strategies working with a growing number of students? Does prenatal exposure to opioids cause the severe problems they’re seeing with students retaining information or is toxic stress more to blame? Where will funding come from for evidence-based prevention efforts and supports for kids in trauma? Nearly two decades into the opioid crisis, why can’t we answer those questions?

The Role of Schools

Turning Point

Both the state of West Virginia and Jackson County have taken steps to slow the spread of the opioid crisis. It started with a wakeup call of the worst kind.

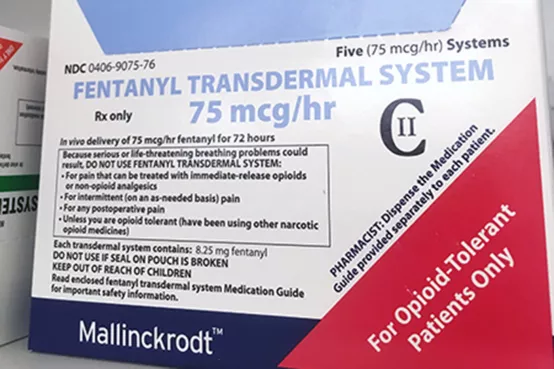

Between 2006 and 2008, 16 teens and young adults in Jackson County died after overdosing on the powerful opioid fentanyl. They were found dead in cars, in bathrooms, and on front yards. The last death was the kindergarten teacher’s son.

With a federal Drug Free Communities grant, the Jackson County Health Department brought together schools, hospitals, law enforcement, mental health care providers, and the faith community to find better ways to educate the public about the signs of drug use and prevention strategies that included identifying classroom supplies that a child could use to get high. It has resulted in teen drug use rates lower than the national average.

West Virginia also pioneered the Handle With Care program that allows law enforcement to inform school administrators immediately after a child has had a traumatic event in the home. Flagging a student means, at the very least, the student won’t be punished for not having his homework or being unable to participate during class.

If Jackson County is ahead of the game in some ways, there is still a tremendous weight on its educators, made heavier by the chronic underfunding of public education. West Virginia spent 11 percent less per pupil in 2018 than it did in 2008, even as the opioid crisis grew exponentially worse.

“We’re trying to teach them to read and do math, but also provide all the love and support and encouragement—that’s a lot in a day,” says Knopp.

“What could we do if we actually had smaller classes [and mental health supports] for any kid who needs it?”

When the school district had better funding, class sizes topped out at 17. These days, class sizes are as high as 26 students to a single teacher, which drastically decreases the amount of one-on-one time the teacher can spend with any one student.

Ripley Elementary has 11 special needs classrooms and an alternative education room that serves children from across the county with more profound behavioral issues. The district just hired a social worker for the first time, but there is still a shortage of counselors and essential services such as play therapy.

“A lot of these stories of drug addiction are coming out of good, middle-class, even well-off families,” says Lori Mahan. “If we had more mental health services and less stigma around using them, these families would stand a chance and we might be able to beat this opioid crisis.”

For More

NEA Resources

Teaching Children from Poverty and Trauma Handbook

The Six Pillars of Community Schools Toolkit

NEA edCommunities Group: Trauma Informed Classrooms/Strategies (You must be a member of EdCommunities to access this content. Registration is free and open to all)

NEA Foundation Grant Opportunity

The NEA Foundation wants to help NEA members everywhere access top-notch professional development—including educators working in communities hit hard by the opioid crisis. If your district cannot cover the cost of training educators in trauma-informed care, consider applying for an NEA Foundation Learning and Leadership Grant as an individual or as a group.

For Further Reading

How Schools Are Helping Traumatized Students Learn Again

As Opioid Crisis Alarms Communities, Drug Education Now Starts in Kindergarten

All Hands On Deck: School-based Programs to Stem Substance Abuse

School Prevention Programs Try to Rein in Heroin, Pill Epidemic

Get more from