Key Takeaways

- Comics can supplement traditional curriculum materials to engage more students.

- Research shows that combining visual and textual elements deepen student connection to lessons.

- Build critical thinking skills with simple comics lessons you can try tomorrow.

In the current political climate, would a Superman comic be considered too “woke” for school kids? The idea makes for an interesting classroom discussion, especially in an environment that threatens anything that smacks of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

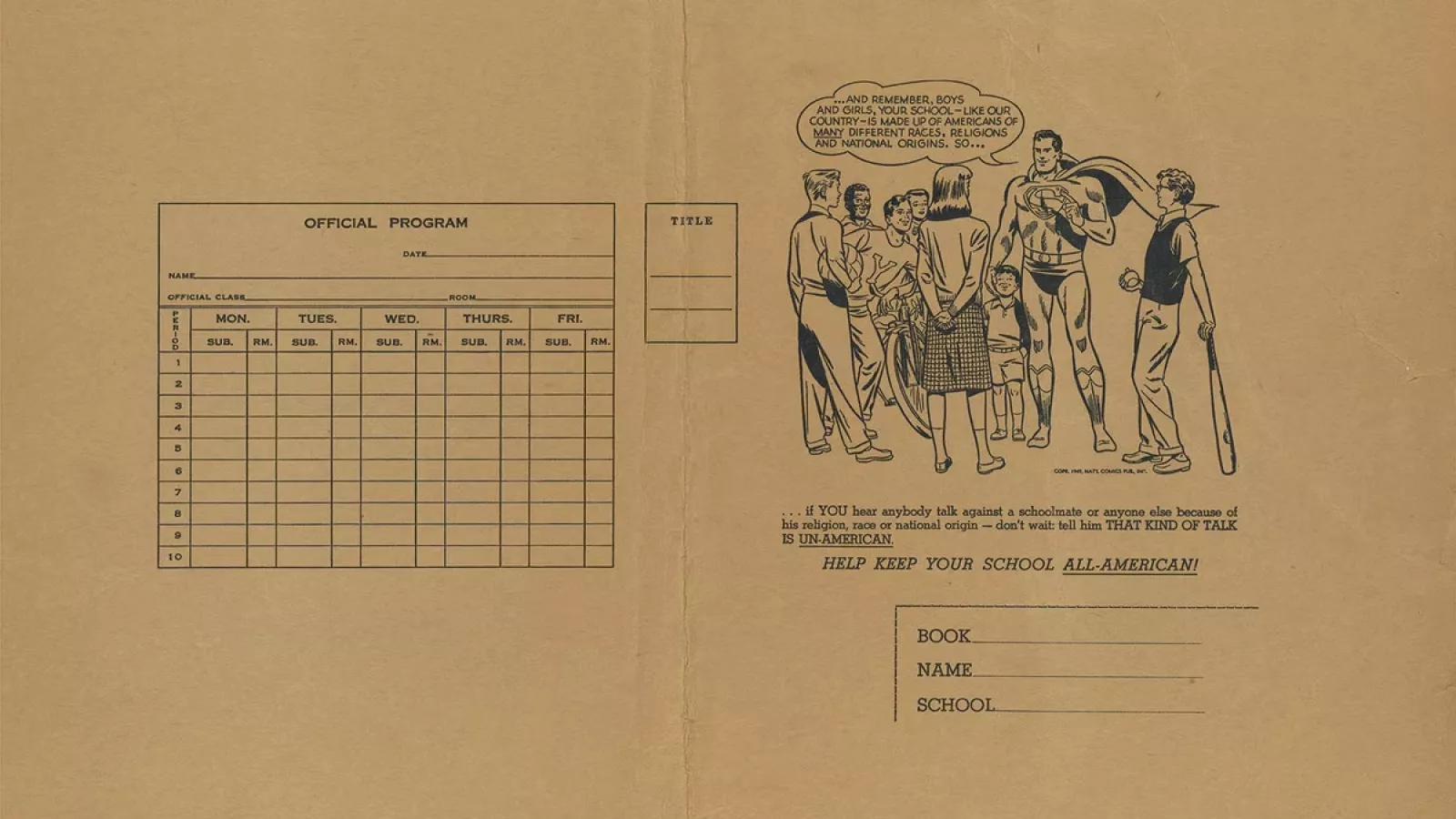

Consider this: In 1949, DC (National Comics) produced a school book cover featuring Superman talking to school children, drawn by Superman artist Wayne Boring.

“…And remember boys and girls, your school – like our country – is made up of Americans of many different races, religions, and national origins. So…if you hear anybody talk against a schoolmate or anyone else because of his religion, race, or national origin—don’t wait: tell him that kind of talk is UN-AMERICAN.”

Was the Man of Steel “woke” or was he voicing a core American value? Discuss!

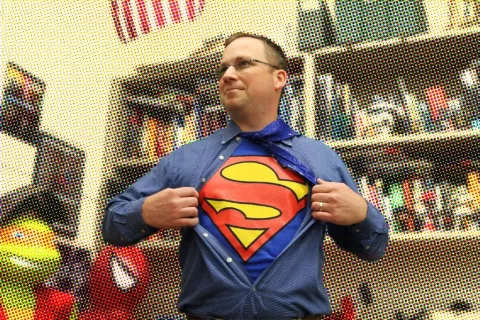

Tim Smyth, a social studies teacher in Pennsylvania, regularly uses comics in his classroom to supplement traditional texts for discussions about history and current events.

“Comic books serve as a time capsule that reflect the news of the day as history is happening,” Smyth says. “History isn’t just kings and queens, battles and dates, it’s made up of stories from a time and place, and comics, which come out weekly, can be used as historic artifacts from different eras.”

Smyth isn’t alone – teachers across the country use comics and graphic novels to supplement classroom lessons as students’ interest in these formats explodes. Comic and graphic novel readership grew by 56 percent in the 2022-2023 school year, according to the School Library Journal.

“Comics and graphic novels allow students to connect with curriculum more deeply, especially if they see themselves in the story,” Smyth explains.

“Truth, Justice, and the American Way” - Superman

It’s not surprising, he says, that Superman would make a statement about acceptance in the wake of World War II as waves of refugees and immigrants arrived in America – just as there are refugees and immigrants today.

“Superman, too, was once an outsider, a newcomer to America,” Smyth says. “A superhero reminding us that we are all Americans sends a powerful message to students.”

For lessons on World War II and other conflicts and the aftermath on societies, Smyth uses a Superman comic from 1985, where he is the sole survivor of a nuclear war. The comic reflects society’s fears of the Cold War and the threat of nuclear bombs more viscerally than a traditional text.

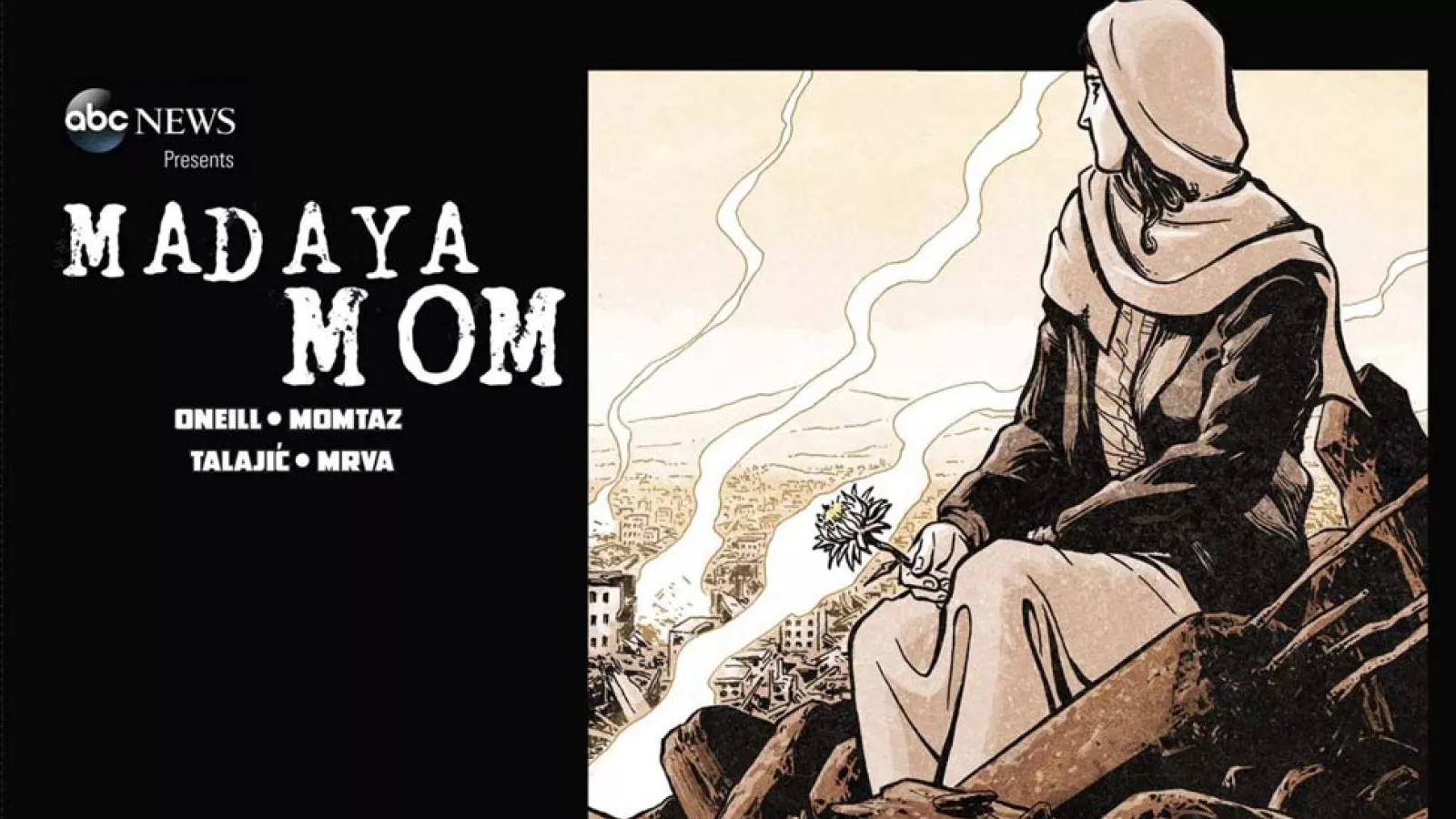

He also uses contemporary comics for lessons, like Marvel’s Madaya Mom, a comic that is also the true story of a mother and her five children who were trapped inside the Syrian town of Madaya for more than a year.

The comic is based on texts she was able to send to ABC News, who partnered with Marvel and Dalibor Talajić, a Marvel artist from Croatia who lived through war during the breakup of the former Yugoslavia.

It shows how the mom fights off starvation, unsanitary living conditions, and threats of violence as they are caught between warring factions in Syria’s civil war.

“Students connect with this comic very emotionally,” Smyth says. “It’s very hard to comprehend 13 million people displaced from their country, but when you boil it down to one person, one family, and show war’s impact through a medium like a comic, it creates a very deep connection.”

They discuss the comic’s historical and social implications and apply them to the human experience of groups experiencing war and persecution throughout history.

“Anyone Can Wear the Mask” – Miles Morales

Reading Madaya Mom, students see that not all superheroes are men in tights with capes.

“Superheroes are not defined by their powers or their physique. Superhero is in the heart. Madaya Mom fits within this category because she finds strength to be human and unhardened,” Dalibor Talajić told ABC News.

It’s in that way that comics can humanize lessons on history and current events, especially when students can see themselves in the characters, Smyth says.

“As Miles Morales says in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, ‘anyone can wear the mask,’” Smyth says. “That’s the power of comics – being a hero is not limited to one accepted monolithic experience.”

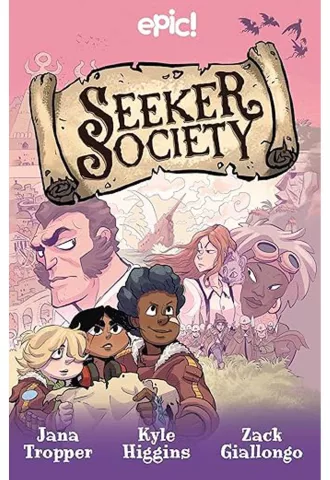

Jana Tropper, who also uses comics in her practice, says that students not only see themselves in comics and graphic novels, but that the format helps reinforce vocabulary from lessons.

“The science shows that brains simultaneously interpret the visual and textual information, and the connection is stronger when they’re together,” says Tropper, a speech and language pathologist at a K-5 elementary school outside of Chicago.

“Images augmenting the word opens a new way of making connections,” she adds. “Teaching with comics embraces brain differences and engagement in visual learning.”

“In Brightest Day, in Blackest Night...” – Green Lantern

The students in Tropper’s classroom have disabilities, including students who are autistic. Tropper has found that comics help them connect with the world around them and build their own communication skills, particularly in lessons where they create their own comics. To do that, Tropper and her students use a popular comic-creation program called Pixton.

She has an autistic student who strongly dislikes storms.

“He was reluctant to go outside when there was even a hint of a cloud. He’s very uncomfortable with weather, and tornado drills make him extraordinarily anxious,” she says.

Enter Captain Coud. There’s a storm forming on the horizon? That’s a job for Captain Cloud!

Tropper helped the student create a comic where he’s a superhero, a version of himself where he could cope with weather changes. They created a visual of him in costume on the playground.

“It gives him a preview of what he could be like outside on a cloudy day,” Tropper explains.

Holy [Literacy] Batman! - Robin

Comics are powerful storytellers, with the art helping to tell the story and conveying its own information, Tropper explains, much like evacuation instructions on airplanes or IKEA furniture assembly guides.

Comics and graphic novels can be used for all students as options to augment, broaden, and deepen curriculum. They can engage reluctant readers, increase comprehension for students working on decoding or working memory, and tap into the power of visual literacy.

“They might not be for every student, but they’re a great option for visual learners,” Tropper says. “One student could read Little Women, while another could read Jo and they could talk about the same concepts without decoding being a gatekeeper. Visual literacy needs to be brought to all content areas.”

“You’ve Got the Costume. You’ve Got the Power.” - Spiderman

Educators in any classroom can use comics in their lessons and be a superhero for their students. Just reach for a comic strip, Tropper suggests.

Make a copy of a comic page, and block out one panel, then ask students to fill it in.

“By drawing attention to the details in the images in the panels before and after the blocked panel, you’re teaching students about inferring,” she explains.

“Calvin and Hobbes or Garfield are good ones—they usually have a setup, a disaster, and then an explanation. If you remove the disaster panel, the wild ideas the kids can come up with about what happened never cease to amaze me!”

Or try removing the dialogue from a word balloon so students have to examine what happens before and after by looking at how others react and what facial expressions convey to infer what the word balloon might say.

“The students make their case about what was said by offering evidence, which is higher level reasoning.”

Next, introduce students to emanata (eh-mah-NAH-tah), the visual elements that emanate from a character that symbolize a character’s internal state – like lightbulbs for ideas, rain clouds for anger, or question marks for confusion.

“Ask students to interpret the enamata in a comic or come up with a set of their own to build critical thinking skills,” Tropper says.

“I Could Do This All Day” – Captain America

“Meeting kids where they are is the only way we can connect with them in this era of increasing needs and decreasing resources to serve them,” Tropper says.

There is an ever-increasing number of students who want to read comics and graphic novels, and they have fun reading and learning from them, she says.

“Educators can get them to learn what we want them to learn with the materials they choose,” she adds. “By letting them choose the medium, they’ll be more engaged.”

Tropper acknowledges that some find comics and graphic novels less serious than traditional prose, but she disagrees strongly, and has seen time and again how effective they are with her students.

“There are incredibly moving tales in ‘just comics.’ We take fine arts seriously, and we take literature seriously, but put them together and some people lose their minds. They decide it doesn’t count. My question is, why can’t school and learning be fun?”

Education News Relevant to You

Get more from