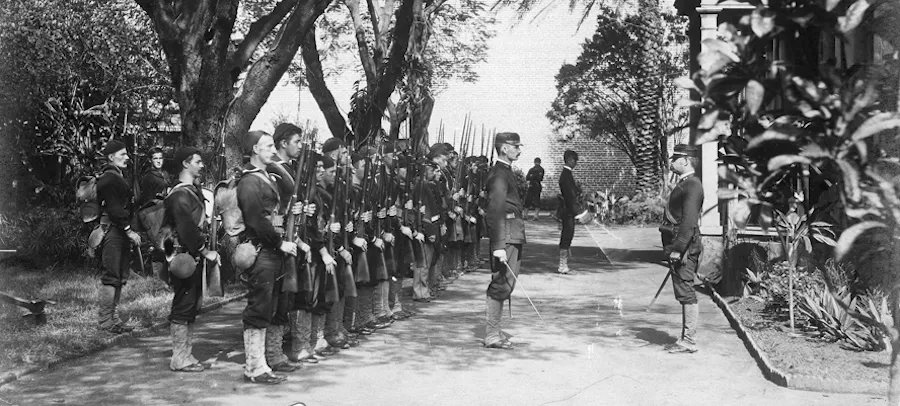

U.S.S. Boston occupying Arlington Hotel grounds during overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893. (Hawaii State Archives)

U.S.S. Boston occupying Arlington Hotel grounds during overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893. (Hawaii State Archives)

In his message to the Congress on December 18, 1893, President Grover Cleveland acknowledged that the Hawaiian Kingdom was unlawfully invaded by United States marines on January 16, 1893, which led to an illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government the following day. The President told the Congress that he “instructed Minister Willis to advise the Queen and her supporters of [his] desire to aid in the restoration of the status existing before the lawless landing of the United States forces at Honolulu on the 16th of January last, if such restoration could be effected upon terms providing for clemency as well as justice to all parties concerned (U.S House of Representatives, 53d Cong., Executive Documents on Affairs in Hawaii: 1894-95, p. 458).”

What the President didn’t know at the time he gave his message was that Minister Willis succeeded in securing an agreement with the Queen that committed the United States to restore her as the Executive Monarch, and, thereafter, the Queen committed to granting amnesty to the insurgents. International law recognizes this executive agreement as a treaty. The President, however, did not carry out his duty under the treaty to restore the Queen, and, consequently, the Queen did not grant amnesty to the insurgents. The state of war continued.

Insurgency Continues to Seek Annexation to the United States

President Cleveland acknowledged that those individuals who he sought the Queen’s consent to grant amnesty were not a government at all. In fact, he stated they were “neither a government de facto nor de jure (p. 453).” Instead, the President referred to these individuals as “insurgents (Id.),” which by definition are rebels who revolt against an established government. Under Chapter VI of the Hawaiian Penal Code a revolt against the government is treason, which carries the punishment of death and property of the convicted is seized by the Hawaiian government.

On July 3, 1894, the insurgents renamed themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i and continued to seek annexation with the United States. Article 32 of its so-called constitution states, “The President, with the approval of the Cabinet, is hereby expressly authorized and empowered to make a Treaty of Political or Commercial Union between the Republic of Hawaii and the United States of America, subject to the ratification of the Senate.” The insurgents always sought to be annexed by the United States.

After President William McKinley succeeded President Cleveland in office he entered into a treaty of annexation with the insurgents on June 16, 1897, in Washington, D.C. The following day, Queen Lili‘uokalani, who was also in Washington, submitted a formal protest with the State Department. Her protest stated:

“I, Liliuokalani of Hawaii, by the will of God named heir apparent on the tenth day of April, A.D. 1877, and by the grace of God Queen of the Hawaiian Islands on the seventeenth day of January, A.D. 1893, do hereby protest against the ratification of a certain treaty, which, so I am informed, has been signed at Washington by Messrs. Hatch, Thurston, and Kinney, purporting to cede those Islands to the territory and dominion of the United States. I declare such a treaty to be an act of wrong toward the native and part-native people of Hawaii, an invasion of the rights of the ruling chiefs, in violation of international rights both toward my people and toward friendly nations with whom they have made treaties, the perpetuation of the fraud whereby the constitutional government was overthrown, and, finally, an act of gross injustice to me.”

Additional protests were filed with the State Department by two Hawaiian political organizations—the Men and Women’s Hawaiian Patriotic League (Hui Aloha ‘Aina), and the Hawaiian Political Association (Hui Kalai‘aina). President McKinley ignored these protests and was preparing to submit the so-called treaty for ratification by the Senate when the Congress would reconvene in December of 1897.

This prompted the Hawaiian Patriotic League to gather of 21,169 signatures from the Hawaiian citizenry and residents throughout the islands opposing annexation. On December 9, 1897, Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts entered the petition into the Senate record.

Under the Queen’s instructions, the delegates from the two Hawaiian political organizations who were in Washington began to meet with Senators who supported ratifying the so-called treaty. Sixty votes were necessary to accomplish ratification and there were already fifty-eight commitments. By the time the Hawaiian delegation left Washington on February 27, 1897, they had successfully chiseled the fifty-eight Senators in support of annexation down to forty-six.

Unable to garner the necessary sixty votes, the so-called treaty was dead by March, yet war with Spain was looming over the horizon, and Hawai‘i would have to face the belligerency of the United States once again. American military interest would be the driving forces to fortify the islands as an outpost to protect the United States from foreign invasion.

Annexation by Legislation

On April 25, 1897, one month after the treaty was killed, Congress declared war on Spain. The Spanish-American War was not waged in Spain, but rather in the Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Cuba in the Caribbean, and in the colonies of the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific. On May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay in the Philippines.

Three days later in Washington, D.C., Congressman Francis Newlands submitted a joint resolution for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to House Committee on Foreign Affairs on May 4. On May 17, the joint resolution was reported out of the committee and headed to the floor of the House of Representatives.

On June 15, 1898, Congressman Thomas H. Ball from Texas emphatically stated, “The annexation of Hawai‘i by joint resolution is unconstitutional, unnecessary, and unwise. …Why, sir, the very presence of this measure here is the result of a deliberate attempt to do unlawfully that which can not be done lawfully (31 Cong. Rec. 5975).”

Queen Lili‘uokalani

Queen Lili‘uokalani

When the resolution reached the Senate, Senator Augustus Bacon from Georgia sarcastically remarked that, the “friends of annexation, seeing that it was not possible to make this treaty in the manner pointed out by the Constitution, attempted then to nullify the provision of in the Constitution by putting that treaty in the form of a statute, and here we have embodied the provisions of the treaty in the joint resolution which comes to us from the House (31 Cong. Rec. 6150).” Senator Bacon further explained, “That a joint resolution for the annexation of foreign territory was necessarily and essentially the subject matter of a treaty, and that it could not be accomplished legally and constitutionally by a statute or joint resolution (31 Cong. Rec. 6148).”

Despite the objections from Senators and Representatives, it managed to get a majority vote and President McKinley signed the joint resolution into law on July 7, 1898. The military buildup began in August of 1898 with the first army base in Waikiki called Camp McKinley. Today there are 118 military sites throughout the Hawaiian Islands and it serves as the headquarters for the United States Indo-Pacific Command.

Many government officials and constitutional scholars could not explain how a joint resolution could have the extra-territorial force and effect of a treaty in annexing Hawai‘i, a foreign and sovereign state. During the 19th century, Born states, “American courts, commentators, and other authorities understood international law as imposing strict territorial limits on national assertions of legislative jurisdiction (Gary Born, International Civil Litigation in United States Courts, p. 493).”

In 1824, the United Supreme Court explained that, “the legislation of every country is territorial,” and that the “laws of no nation can justly extend beyond its own territory (Rose v. Himely, 8 U.S. 241, p. 279),” for it would be “at variance with the independence and sovereignty of foreign nations (The Apollon, 22 U.S. 362, p. 370).”

In violation of international law and the treaties with the Hawaiian Kingdom, the United States maintained the insurgents’ control until the Congress could reorganize the insurgency so that it would look like a government. On April 30, 1900, the U.S. Congress changed the name of the Republic of Hawai‘i to the Territory of Hawai‘i. Later, on March 18, 1959, the U.S. Congress, again by statute, changed the name of the Territory of Hawai‘i to the State of Hawai‘i.

In 1988, Acting Assistant United States Attorney General, Douglas W. Kmiec, drew attention to this American dilemma in a memorandum opinion written for the Legal Advisor for the Department of State regarding legal issues raised by the proposed Presidential proclamation to extend the territorial sea from a three-mile limit to twelve (Opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel, vol. 12, p. 238-263). After concluding that only the President and not the Congress possesses “the constitutional authority to assert either sovereignty over an extended territorial sea or jurisdiction over it under international law on behalf of the United States (Id., p. 242),” Kmiec also concluded that it was “unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea (Id., p. 262).”

Kmiec cited United States constitutional scholar Westel Woodbury Willoughby, who wrote in 1929, “The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was not denied, but it was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act. …Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature enacted it (Id., p. 252).”

In 1910, Willoughby wrote, “The incorporation of one sovereign State, such as was Hawaii prior to annexation, in the territory of another, is…essentially a matter falling within the domain of international relations, and, therefore, beyond the reach of legislative acts (Willoughby, The Constitutional Law of the United States, vol. 1, p. 345).”

United Nations Acknowledges the Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom

In a communication to the State of Hawai‘i dated February 25, 2018 from Dr. Alfred M. deZayas, a United Nations Independent Expert, the UN official acknowledged the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. He wrote:

“As a professor of international law, the former Secretary of the UN Human Rights Committee, co-author of book, The United Nations Human Rights Committee Case Law 1977-2008, and currently serving as the UN Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).”

A state of peace between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States was transformed to a state of war when United States troops invaded the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16, 1893, and illegally overthrew the Hawaiian government the following day. Only by way of a treaty of peace can the state of affairs be transformed back to a state of peace. The 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, mentioned by the UN official regulate the occupying State during a state of war.