Key Takeaways

- Special education students along with their parents and educators have faced uniquely complicated challenges during the pandemic.

- A large population of students didn’t have the technology or internet access needed to participate or complete school work from home.

- Thanks to staff dedication, student resilience, and stronger partnership with families and communities, many educators and students have succeeded.

Creativity in Crisis

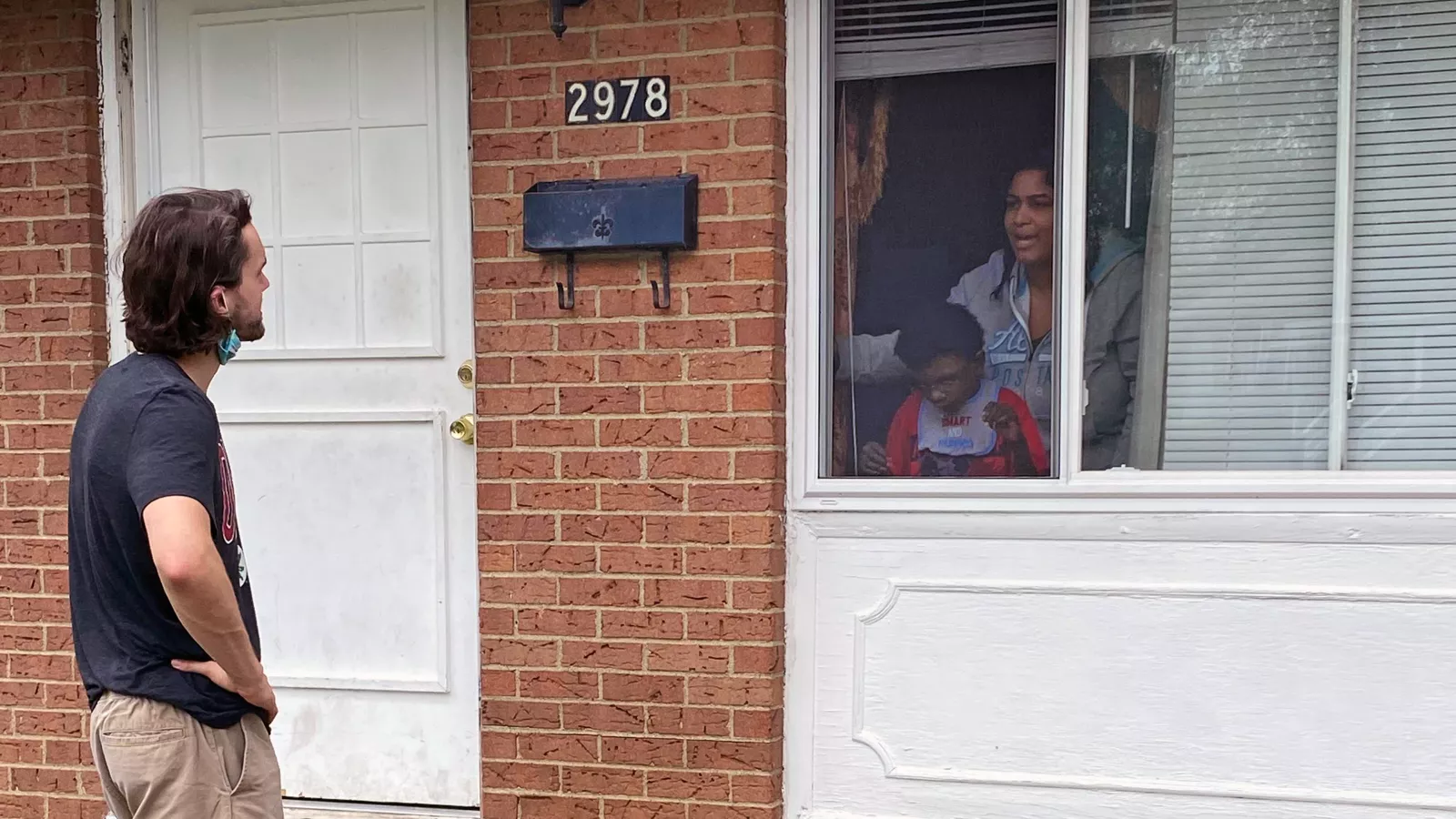

In the early spring of his fifth year teaching special education, Chris Williams was grateful for each measure of progress made by his second-and third-grade students, most of whom have orthopedic impairments or multiple disabilities.

Then the world stopped.

“It was like running a marathon, getting to mile 22, and then suddenly being sent home,” he says.

Williams is an intervention specialist at Colerain Elementary School in Columbus, Ohio, and is a runner himself. He knows that special education is indeed a marathon. Gains are achieved in increments, after a lot of time, resolve, and effort. Getting cut off mid-stride by COVID-19 hurt.

Special education students along with their parents and educators have faced uniquely complicated challenges during the pandemic. Their stories illustrate how they faced those challenges head-on and what they learned along the way.

Columbus Special Education Students Overcome the Digital Divide

Though the sudden closing of schools and scrambling to continue instruction posed the most complicated challenge of Williams’ career, he was determined to make it work. There were issues of access and equity and concerns about the well-being of his students and their families. Plus, he had to figure out how to engage and assist students, who relied on close proximity for instruction.

The same challenges have tested the staying power of special educators everywhere. But with a combination of trial and error, creativity, and a lot of hard work, many educators and students have succeeded.

Equity is essential

Within days of school closures, the inequities in technology access were revealed under a glaring spotlight. Students with no devices or internet access fell off the grid, and educators moved mountains to get them back on. The educators created, printed, and delivered paper learning packets. They worked with districts to find more devices for families. In some areas, they even created Wi-Fi hotspots on buses so students could sit in school parking lots to access online classes.

“The disparities were painfully obvious,” says Williams. “Teaching in a large urban district, we saw the impact quickly on our students.”

A large population of students didn’t have the technology or internet access needed to participate or complete school work from home, and it took a long time and total staff dedication to get everyone what they needed, he says.

“One major takeaway for me was the importance of equitable housing, reliable internet access, and necessary technology....It felt like we were starting behind the starting line, whereas other districts equip students with laptops or iPads as soon as they enter elementary school.”

As far as equity within the special education population, Williams acknowledges that it was particularly challenging to replicate the school day virtually.

“We are so hands-on and use so many devices, resources, and materials that cater specifically to our students and their needs,” he says.

Some special education students around the country had the tools they needed—such as larger monitors, special keyboards, and other assistive technology—provided by their districts. Others had to purchase or find the technology themselves or do without.

“One major takeaway for me was the importance of equitable housing, reliable internet access, and necessary technology,” he says. “Our district, through CARES Act [coronavirus aid] money, finally received devices for every student in the district by the beginning of the school year in the fall. It felt like we were starting behind the starting line, whereas other districts equip students with laptops or iPads as soon as they enter elementary school.”

Students and families are resilient

Most of Williams’ students have impairments that affect their physical abilities, and some have disabilities that impact their speech, behavior, and learning.

“Of course, it’s been really challenging at times, and we really couldn’t wait to get back in person, but I am extremely proud of everything we’ve accomplished,” he says. “The amount of work it has taken to establish reliable ways to communicate—synching schedules, establishing where students need to be at home, how to set up their laptops so they can see everybody, figuring out how they communicate and use their individual adapted technology, and keeping it all charged, was enormous work, but totally successful.”

The moral of the story, he says, is that his special education students still grew and learned.

“I reject the idea that students can’t adapt even when it’s really, really hard,” he says. “With my student population, we rely on close proximity methods when we are in school, but we had to balance that with not putting anyone at risk. And there is nothing like seeing a group of second and third graders seeing their friends’ faces and saying ‘hi’ and ‘bye’ to each other.”

Some of Williams’ students found their groove more quickly than others. One was uncomfortable being on camera, didn’t like being on Zoom for long periods of time, and wasn't able to consistently participate in live online classes. But the student found a way to engage.

In one instance, the student had missed a class on Nickelodeon slime, but later submitted a bunch of documents online. “He’d watched the class recording on his own, then made the slime at home with his family,” Williams recalls.

“He did the whole experiment, filmed it, and shared it with the class. That was really special.”

Special educators rely on body language, eye contact, and other face-to-face interactions to make and strengthen connections with their students—a challenging feat with distance learning. But Williams found that it’s not impossible.

Another one of his students was fairly quiet during online classes. One day, the student had his head down and seemed out of sorts, so Williams called the boy’s name to ask what was going on.

A native Spanish speaker who uses an iPad and his older brother to sometimes help with translation, Williams asked what he was doing for the weekend and thought he heard the student say “FIFA”—a soccer video game that Williams also likes to play.

“Did you say FIFA? The video fútbol game?” Williams asked.

The boy looked up and started shouting “FIFA! FIFA!”

“Dude, that’s my favorite video game!” Williams responded. When Williams played the trailer for the game on his shared screen, the boy started cheering.

“He lost his mind he was so excited!” Williams says.

He and his colleagues pride themselves on finding that one thing that allows them to connect with each student, But doing that in a virtual setting felt like finding a needle in a haystack.

With speech and communication disabilities, many students can’t voice what they are interested in or what they want, so the educators continually try new things to connect

and engage.

“We cleared a major hurdle and now have that essential connection,” he says. “My colleagues and I talked about it for days.”

Tip for closing the tech gap

Urge Congress to invest more in the E-Rate Program, which ensures that schools and libraries have ample bandwidth for all students and patrons. Funding E-Rate would quickly provide schools with Wi-Fi hotspots, modems, routers, and devices for online learning. To learn more, go to educationvotes.nea.org/issue/homework-gap.

Family-School Partnerships Have Grown Stronger

Christopher Edmiston, who lives in Alexandria, Va., loves Peppa Pig and all things Sesame Street. His favorite shirt says “Part Elf,” and his eyes sparkle with equal parts magic and mischief. It’s hard to imagine that this energetic, athletic five-year-old once struggled with nutrition.

“He has some speech and developmental delays because of the life he had before,” says his mother, Melissa Edmiston, who along with her husband, Clark, adopted Christopher from an orphanage in China when he was two years old. Christopher had a repaired cleft lip and palate when he was a baby, and he struggled not only to speak in his early years, but also to chew and swallow food.

With additional medical support, nutrition, and love from his family, Christopher thrived and was on track to start kindergarten with an Individualized Education Program last fall. Then the pandemic hit, and all of the early education supports and therapies he was receiving ground to a halt.

As everyone slowly gained their footing with distance learning, his instruction resumed, but the Edmistons and Christopher’s educators agreed that delaying kindergarten for another year would be best.

“He’d been making such good progress, and then on top of all of the COVID stress, having to decide to wait on kindergarten was devastating,” Edmiston says.

“I now know both of my kids’ teachers in a way I haven’t before. We’re in communication more than ever, because it’s harder for them to tell what’s going on at home through the computer screen.”

But being home with both of her kids, essentially sitting in their classrooms with them while working in the same room, she feels more attuned to what’s going on in their education, especially with Christopher.

“I sat right next to him during his classes; he couldn’t do it without me beside him,” Edmiston says. “I now know both of my kids’ teachers in a way I haven’t before. We’re in communication more than ever, because it’s harder for them to tell what’s going on at home through the computer screen.”

She says their partnership has been stronger and she feels more plugged in to what’s going on from day to day.

“I had less of an idea what they were teaching before because I wasn’t right there in the building, and Christopher didn’t have the articulation to tell me. But now I know they sing a certain song to learn about the weather, for example. So now we can sing it on a Saturday morning or on a family walk,” she says.

Parents can reinforce lessons at home

Christopher’s early educators sent home a package of learning materials including a journal, a calendar, a weather chart, a roll of paper for kids to trace their bodies and draw in features, and Play-Doh for a sensory activity during lessons.

Christopher’s weather chart hangs from a door so the family can talk about it throughout the week. He draws and traces objects on his paper roll and writes in his journal with help from his mom.

After hearing more about the lessons, Melissa Edmiston chooses books to read that follow themes, such as talking about feelings.

Christopher’s teacher is working on two- and three-step directions, which is hard to do virtually, so Edmiston can reinforce these lessons at home: “Christopher, touch your head, then nose, then your ears,” or, “Christopher, pick up your shoes, take them to your room, and put them in your closet.”

We all need a little ‘grace’

Christopher was able to return to in-person instruction in the fall, but there are still struggles. That’s when Edmiston remembers the word “grace.”

“I’ve learned to be more gentle with myself,” Edmiston says. “Expectations have to look different right now, and it’s been incredibly hard for all of us across the board. This isn’t normal, but as a collective group, we’re doing the best we can. That means pausing for a break and remembering that everyone is doing their best, and no one is handling the pandemic situation easily, let alone perfectly. Acknowledge that, and remember it’s all going to be OK.”

If a kid has a breakdown, or some days are really hard, take a pause. It’s not going to set anyone back too far if a parent decides to let their child take a breath, she says.

Tips for maintaining family partnerships

- Send home hands-on activity packets that reinforce classroom lessons.

- Invite parents to observe classroom lessons in person.

- Invite parents to a Zoom call to learn about their children’s classroom lessons.

- Record videos of lessons so parents can follow asynchronously.

- Offer recorded content for students to access at their own pace.

Education Support Professionals Prove Critical—Again

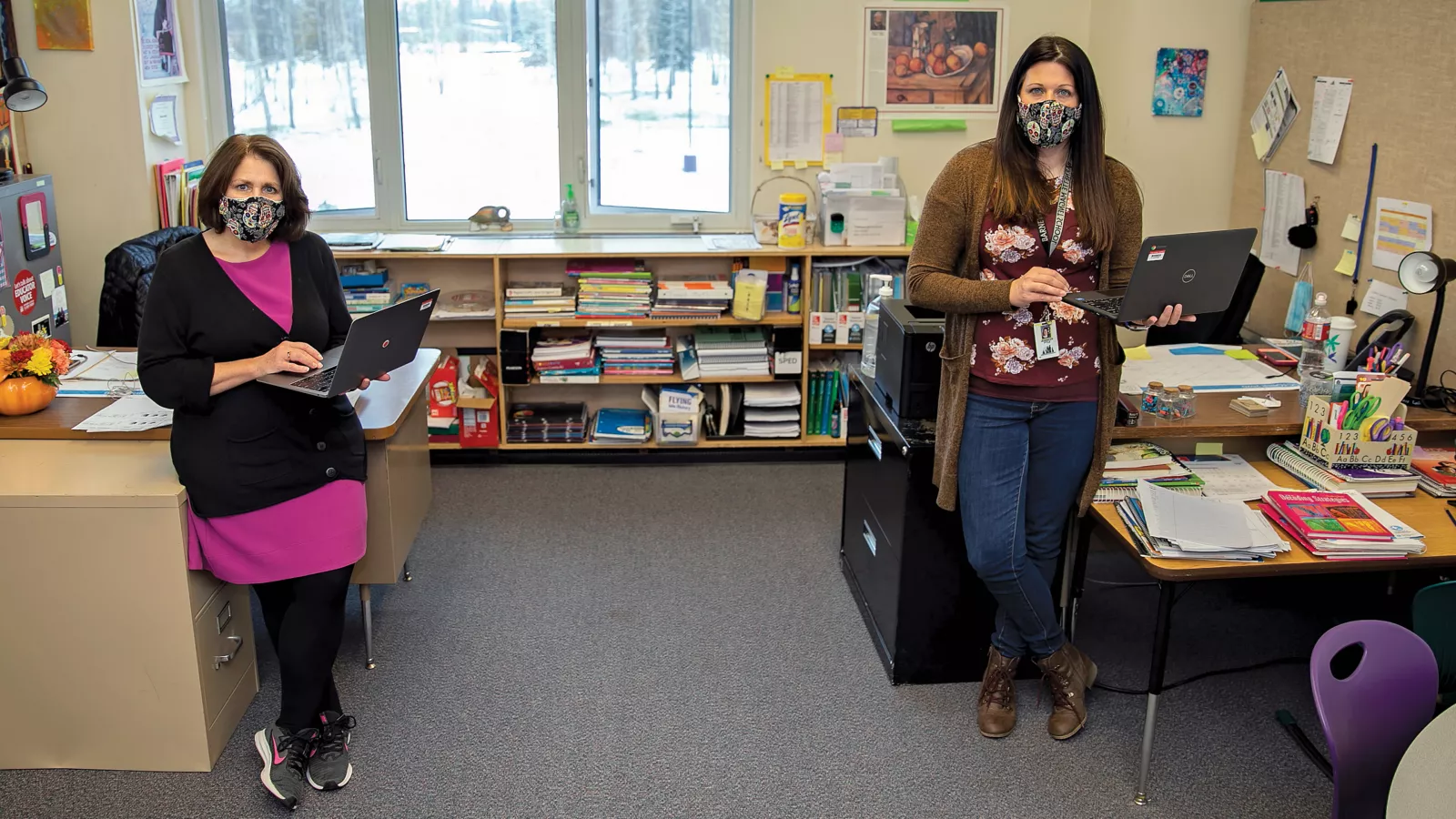

Tammy Smith has been an educator for nearly 40 years. She works hand-in-hand with paraeducator Jennifer Pyle at Barnette Magnet School, in Fairbanks, Alaska. Smith is the only special education teacher at the school, and most of her students have learning and behavioral disabilities.

Together, the duo works with about 25 students who rely on both Smith and Pyle to nurture their learning.

Barnette Magnet School is a K–8 school, so they could be working with a 6-year-old in the morning and a preteen in the afternoon. Like all schools, Barnette Magnet School struggled at first to get everyone online and to figure out how to offer instruction. Smith and Pyle’s first step as a special education team was to reach out to families.

“We knew we had to call those parents at least once every week,” Smith says. “They were confused. The students were confused. But we were able to provide them with a sounding board, answer questions about what we wanted them to work on and what the general education teacher wanted. We were their liaison.”

In the spring, Smith says the entire school community was in survival mode. By fall, they were much better prepared and were able to see some progress, but none of it would have been possible without the school’s team of education support professionals (ESPs).

“That’s the big piece for me—how critical ESPs are. Throughout this time, I’ve been working so closely with my para and the other paras—our behavior aide, our classroom aides,” she says.

“We all had to be a part of every single conversation. That is key. ESPs have worked so hard to support the classroom teachers and everyone in the school.”

ESPs prepared and got lunches out to buses and to families. ESPs cleaned out lockers last spring, bagged up belongings, and returned them to students. They checked out computers and Chromebooks for distance learning. They put together packets.

“They literally did whatever was needed to keep the school functioning, and they continue to do it now,” Smith says. “All job categories, all pitching in and being tasked with more than their regular services. Everyone now knows how critical they are.”

Of course, the students already knew.

ESPs help provide a safe space

After the school building closed, “you could tell they were lost,” says Smith of her students. “They were mourning the loss of connection with school, and some of them started showing up at our lunch lady’s door every day. They just wanted to stand there and talk. They knew that was a safe place.”

Like in communities across the country, Fairbanks has students with difficult home lives. There are families with drug and alcohol addictions, domestic violence, and poverty. Students who have turmoil at home look for calm and stability at school. ESPs help provide it.

Social-emotional learning and “whole child” education isn’t new, but it went into overdrive during the pandemic, highlighting the need to make students feel safe and secure as a precursor to learning, particularly for special education students who thrive on consistency and routine.

From bus drivers delivering meals with an encouraging smile and wave, to social workers and counselors checking in to offer mental health support for anxious and depressed students, to a food service worker opening up her yard to talk to lonely, confused children, ESPs helped public schools cope with the global pandemic every day, in big and small ways.

“When policymakers ask how we can support public schools, we all need to say, “Hire more ESPs!’” Smith says.

She also learned that ESPs, especially the para-professionals who work with classroom teachers, must receive more professional development. The sudden pivot to online learning left everyone reeling. ESPs needed the same training as teachers so they could help out with the technology.

Tips for supporting ESPs

- Work with your affiliate to promote ESP professional development.

- State and local budgets have taken a big hit from the pandemic. As districts face huge budget shortfalls, they might seek to privatize ESP jobs to save money, which hurts schools, students, and the entire community. Find out how to advocate for job security for ESPs and against privatization.

- The more ESPs that are part of the NEA family, the stronger our voice becomes. Encourage ESPs in your school to become NEA members.

We’ve (Mostly) Figured Out the Technology. Let’s Keep It Up!

“I’m a paper and pencil girl,” admits Alaska special education teacher Tammy Smith. “But I’ve been very intentional in learning technology because that’s where students are going, and now I’m more familiar than ever.”

Despite a sharp learning curve, educators across the country have learned how important it is to have many methods of communication and opportunities for collaboration with families using online platforms.

These tools could be used in the future for a snow day or when a student has surgery or needs to be out for a while.

More ed tech confidence

“Now more than ever, our ed tech confidence has been boosted,” say Gwyneth Jones, a teacher, librarian, and educational technology leader at Murray Hill Middle School, in Howard County, Maryland. “Teachers are now daring to integrate and infuse instruction with new learning tools to engage our students and to enhance their learning experience.”

Resources that once seemed frivolous now shine as a meaningful addition to our tech tool kit, she says. “Flipgrid, Jamboard, Peardeck, GSuite, and … YouTube videos all add to what we can offer to engage and involve our students to enhance their learning experience.”

Project-based learning for the win!

Students feel empowered and have a sense of ownership when they can choose the product they wish to create to demonstrate information mastery. Project-based learning (PBL) offers this opportunity and shines in a virtual environment—but it’s even more vibrant in person, Jones says. Whether students create a public service announcement, promotional brochure, broadcast media script, flyer, or Podcast proposal, these projects help connect students to the real world. PBL also provides essential life skills, such as critical thinking and time management.

General and special education students and educators have embraced technology. “Special education kids respond enthusiastically to technology,” Jones says. “Just offer a little bit of modeling and guidance to introduce it to the kids and then step back a wee bit and let them explore!”

Get more from