Key Takeaways

- NEA members and their affiliated unions across the country are helping to solve problems and improve the everyday lives of educators and students.

- Learn how NEA members and their unions are working together.

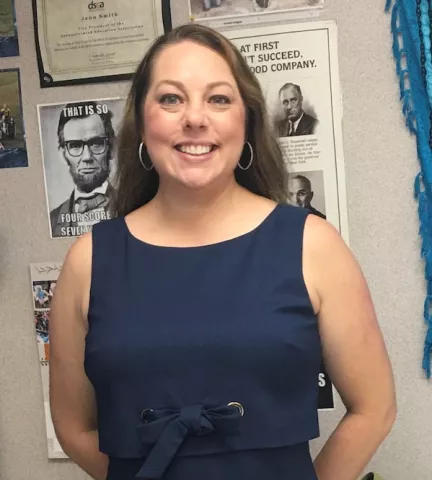

Victoria Pescaia describes herself as a military brat—one who fell in love while at the University of Hawaii. When her parents relocated to the U.S. mainland, she stayed behind, and decided to become a teacher.

While love may have kept her in Hawaii, the salary for teachers nearly drove her out.

Until recently, Hawaii paid teachers according to classifications based on education rather than years of experience. All other pay raises were negotiated.

This meant that teachers with decades of experience might make the same salary as new teachers—a pay structure known as salary compression.

Pescaia, who recently became a technology coordinator on the island of Oahu, earned a master’s degree in 2002 and paid to take several continuing education class credits to help bump up her salary. But still it’s taken her 27 years to get close to the top of the salary schedule, which finally happened in February.

In 2020, her daughter was a high school senior with dreams of attending college in the continental U.S. Her daughter had earned multiple scholarships, but that still wasn’t enough.

So Pescaia started looking for a second job. But that would have meant dropping her volunteer roles, which included mentoring the robotics teams; advising community service clubs; and helping with after-school events.

The stress became so overwhelming that Pescaia even considered moving to the mainland, where the cost of living is significantly lower.

But thanks to the efforts of the Hawaii State Teachers Association, in May 2022, lawmakers approved a budget that includes more than $164 million to end salary compression and fill other funding shortages.

“Many veteran teachers like me love our students and love teaching, but we didn’t see hope in making salary gains. And some of us were planning to retire early, making the teacher shortage crisis in Hawaii worse,” Pescaia says. “We are here to stay if we can afford it! Addressing salary compression gives us hope and will encourage veteran teachers to stick around. HSTA’s support ... has made that possible.”

Pescaia’s story is just one of the many ways NEA members and their affiliated unions across the country are helping to solve problems and improve the everyday lives of educators and students. Here are five more union solutions.

Solution 1: Paid Leave for Military Families

When first-grade teacher Sophia Carter’s son asked her to be part of his deployment and post-deployment ceremonies at Camp Pendleton, in California, she of course went to support him. But she was docked two days’ pay by her district, in Muskogee, Okla., and had $500 taken out of her paycheck to cover the substitute in her classroom.

“I felt that after all that a military family sacrifices, this was unfair,” Carter says.

She approached her union, the Muskogee Education Association, and its bargaining committee members went to work. The new negotiated agreement between her union and district now includes permanent language providing up to three days of military family leave, available twice per school year.

Now, educators like Carter can leave to attend military graduations, deployments, returns to stateside, and other important milestones for spouses, children, parents, grandchildren, and other family members.

Solution 2: Affordable Day Care for Educators

Some people think of NEA as a place to get liability insurance and discounts,” says Bethany Jarrell, a preschool teacher of 17 years and vice president of NEA-New Mexico (NEA-NM). “But it’s so much more than that. We are whatever our members need us to be.”

In Santa Fe, educators needed their union to be advocates for affordable child care. The city is one of the most expensive in the state. Housing and child care costs can be staggering, making it hard for teachers to live in the community where they work.

Last summer, NEA-Santa Fe leaders surveyed their members and found that of those who paid for child care, the average monthly cost was $954, with some paying more than $2,000 a month.

Members took their concerns to the bargaining table in late 2021, and by April 2022, the school district announced it would pilot an early childhood center for employees starting this school year.

Educators who have children ages 12 months to 3 years will be offered 70 percent of the available openings. District staff will have access to the remaining slots. The cost will range from $150 – $250 a month.

Solution 3: More Education Funding

Child care is a top priority for many other families across the state as well. This is why NEA-NM is working to increase funding that would support more families with early child care needs.

Jarrell is a part of a statewide coalition working to pass a constitutional amendment that would increase funding for early childhood education and K–12 programs.

If the amendment is approved by voters in November, it would allocate $26 billion dollars to provide access to free preschool as well as child care, home visit programs for new parents, additional support services for special education, and more. The funding would better support low-income and Native American students, English language learners, and students with disabilities throughout New Mexico.

“The work we do can change people’s lives for the better,” Jarrell says. “And we’re not an unknown or external organization that’s coming into communities. We’re your classroom teachers and librarians, nurses, secretaries, bus drivers, and all the professionals who make up our membership and help make the changes our students and educators deserve.”

Solution 4: Sabbaticals for Professional Development

Jenn Smith went from teaching middle school social studies for 21 years to helping the Delaware Department of Education revamp its teacher evaluation system.

How did she make such a big impact? She was accepted into NEA’s Professional Practice and Policy Fellowship program, which offers participants a one-year paid sabbatical to work on a professional learning opportunity of their choice. The leave from work is negotiated by the state union, in this case, the Delaware State Education Association.

This time spent out of the classroom, in 2021 – 2022, allowed Smith to work with her union and a Delaware education department steering committee to make essential improvements. Smith had taught under the state’s former evaluation system—born out of the punitive No Child Left Behind era—and used this experience to help design a system that nurtures student learning.

Now called the Delaware Teacher Growth and Support System, the state piloted the new program last year, providing educators with ongoing observation, feedback, and support to drive teacher growth. In the new system, administrators become more like coaches, and educators get the support they need to help their students grow and learn.

“No one knows our experiences better than we do,” Smith says. “And being a part of the union has given me this seat at the table and voice in the room, and I value that.”

Solution 5: Protection for LGBTQ+ Educators

Shortly after Louisiana music teacher Blaine Banghart came out to school administrators as transgender and nonbinary, they became the target of one woman’s outrage. The woman was upset by an online photo of Banghart wearing colorful clothes and pins that expressed Banghart's honorifics and pronouns. Banghart goes by Mx., and their pronouns are they/them.

“She copied that picture and started posting it to different neighborhood and school groups,” Banghart says. “On her personal social media, she posted how ridiculous I am and shouldn’t be allowed to teach. She called me ‘it.’”

School administrators received hundreds of phone calls and emails calling for Banghart’s resignation. Complaints first centered on their gender identity. But since identity is protected under federal law, the attacks shifted, accusing Banghart of violating a nonexistent school dress code.

While Banghart started out alone in this fight, they certainly didn’t finish alone. At the time Banghart was attacked, they were not a member of their NEA-affiliated unions. But that didn’t matter, says Sheila Washington, of the Louisiana Association of Educators (LAE).

“Our main goal, even if they had not joined the union, was to make sure they felt the support of the local, state, and national associations,” Washington says.

LAE staff reviewed paperwork that Banghart had received from the administrators, informed them of their rights, and drummed up support to confront the small, but vocal, group of people who were harassing them.

“I felt very alone when all of this started, and so knowing I now have my union behind me is very helpful,” says Banghart, who is now a member. “Sometimes we’re so closeted and feel so alone, but the union has introduced me to a few other teachers that are in similar situations … and has brought us together. It’s been amazing.”

In the end, the board took no punitive action, and Banghart remains a teacher today.

These stories are snapshots of how NEA members and their unions are working together. Across the country, thousands of members like these are using their experiences and voices to improve the daily lives of educators and give students the public schools they deserve.

Check out nea.org/win to learn how members are winning in every state.