Key Takeaways

- Last summer, as Collin College raced to re-open for in-person classes, faculty asked them to hit pause. Consider more online classes, they said.

- When faculty voices were ignored, several faculty members started a small chapter of the Texas Faculty Association. That got the attention of college administrators—and not in a good way.

- Two faculty members, including one who authored the Faculty Council's resolution on safety, were fired. They were told they were excellent educators. That wasn't the problem.

[Editor's Note: On Nov. 3, 2022, Suzanne Jones was reinstated to the faculty of Collin College. In settling Jones' lawsuit against them, Collin agreed to pay her $250,000 to teach into 2025, and acknowledged she "is a great teacher." The college also will pay for Jones' $145,000 in attorney's fees. "We hope her reinstatement serves as a reminder that college professors have the same rights to free speech and association as other Americans do," said the Texas Faculty Association and Texas State Teachers Association, in a statement.]

As the school year comes to a close, Suzanne Jones’ students have just one question: Will they see her again in the fall?

So far, the answer is no.

Jones, a well-respected professor of education at Texas’ Collin College, was effectively fired this spring after speaking up for student and faculty safety during the COVID-19 pandemic and organizing the Collin College chapter of the Texas Faculty Association (TFA), which is affiliated with the Texas State Teachers Association (TSTA) and NEA.

Also fired was Audra Heaslip, a humanities professor and fellow TFA member who helped write the Collin College Faculty Council’s June 2020 resolution urging administrators to rely more on online classes and enforce mask-wearing on campus.

The terminations of these educators—because they spoke up for student safety—have stunned faculty and students all over the U.S.

But none are more stunned than Jones, who spent 20 years at Collin, and her students.

“When she ended up telling us about how she and Dr. Heaslip were getting terminated, we were so shocked,” says Tatiana Oney, an aspiring teacher who this year was president of Collin’s Aspiring Educators, a group Jones started.

“Because we know how amazing a professor she is!”

Safety First

The problems for Jones and Heaslip started last summer. In June 2020, the cumulative number of cases in Collin County, which includes Plano and other Dallas suburbs, was rising exponentially—from around 1,200 people at the beginning of the month to 3,000 on July 1, according to state government reports.

This ballooning in COVID-19 cases and deaths was happening across the U.S., prompting hundreds of colleges and thousands of school districts to revise their plans for in-person learning in the fall. On most college campuses, faculty were asked if their classes could easily transition to online platforms, and what support was necessary to make that happen. Students and families were asked what safety measures were essential to them.

The terminations of these educators—because they spoke up for student safety—have stunned faculty and students all over the U.S.

These questions weren’t asked at Collin, faculty noted. So, in late June, Collin’s Faculty Council passed an extensive resolution—the one Heaslip helped draft—calling on Collin to include faculty and staff in planning and to move classes online, when possible. “The president likes to say we were petitioning for 100 percent online. That was never what we said,” says Jones.

The resolution also recommends requiring faculty, staff and students to wear face masks; moving classroom desks at least six feet apart; and developing plans around contact tracing. It points out that simply asking people to stay away from campus when they feel sick—as the administration’s re-opening plan did—isn’t adequate.

More than 130 faculty members signed the resolution, which concludes by saying: “These discussions and proposals are intended to bring forward sincerely held concerns by members of the Collin community. We do not wish to subvert or impugn the college leadership in any way. Rather, the purpose of this document is to create a dialogue in the hopes that the administration will consider adjusting its plans in a way that addresses the critical and urgent health concerns laid out here.”

A Dedicated Teacher

At the time, Jones remembers thinking that the resolution was standard stuff. Colleges across the U.S., including in Texas, were moving their classes online. When she signed it, her only comment was that, if she continued teaching in-person classes, she’d like to get a microphone for her classroom. “I wasn’t pushing in any extreme way!” she says.

And, in fact, she did continue teaching in-person classes: Introduction to Teaching, Learning Frameworks, and a class on working with special populations of students. She wore a face mask, as did her students, because the state of Texas mandated their use.

Even this year, despite the challenges of teaching through a pandemic, Jones loved being in the classroom. For 20 years at Collin, she has worked with future teachers, helping them learn the basics of teaching, earn an A.A. degree, and transfer to four-year universities. “We have wonderful success rates for students who transfer on,” she says.

Oney is one of those students. After two years at Collin, she’s transferring to the University of North Texas, where she’ll earn her degree in elementary education with an additional endorsement in English for Speakers of Other Languages. She learned so much from working with Jones in the Aspiring Educators program, she says.

The most valuable lesson?

“She taught us how to be an advocate for our students,” says Oney.

Fear Rises

By August 1, the number of people who tested positive for COVID-19 in Collin County hit 6,353. That month, Collin College President Neil Matkin wrote an email to staff saying, “The effects of this pandemic have been blown utterly out of proportion.” In the same email, he also argued that COVID-19 death numbers were “clearly inflated.”

On September 1, the number of people testing positive in the county topped 11,000. The following month, it surpassed 17,000. Among those who died from the virus in October was Collin student Rogelio Martinez. Matkin shared the news at a board meeting a few weeks later; it’s unclear if any of Martinez’ classmates or instructors were informed directly.

In November, a local television station reported on the lack of information provided by Collin College to employees and students about COVID-infected people on its campuses. At the time, these “COVID dashboards” were common among school systems and colleges in Texas, and across the nation. “While the caliber of information varies, Collin College is noteworthy because it refuses to publicly divulge anything,” the story notes.

The story also quotes Heaslip saying, “I asked could the college please make the numbers available, at the very least to the employees, because the majority of employees, faculty and staff are required to go to campus. And no one has any idea if the college is a hot spot,” she said. “Nobody has any idea if maybe there’s one case or maybe there’s 20 or 200.”

The lack of information was scary, Jones recalls. “They told us nothing. Nothing,” she says. Students and faculty worried that they wouldn’t know if they came into close contact with an infected person. Without that information, they could potentially spread the virus to so many other people—children, elderly parents, immune-compromised students.

Seeking More Input

As a former TSTA K12 member, Jones knew faculty could have a bigger voice in safety issues if they spoke up as a group. She recalls saying to a colleague, “Hey, if we can get just seven people, we can form a TFA chapter and maybe we can have some input.”

She and Heaslip and a handful of others joined, and their little chapter was listed on the TSTA website. Somebody saw it and told Jones’ dean, who called her in September saying, “we just cannot be associated with a union. We can’t have Collin College listed on any union website,” Jones recalls. “I sent him an email the next day saying, ‘I’ve had it taken off, but I want you to understand what unions do….’ I was so naïve!”

Decades earlier, when Jones belonged to TSTA, she recalled that her "administrators celebrated her involvement." Those administrators knew TSTA’s professional development would help her become a better teacher, she says. But in 2020, Jones’ colleagues warned the award-winning educator to be careful. “Again, I was so naïve,” she says. “I was thinking, I’m a great teacher! I have great evaluations!”

The fact is, she says, “As soon as we started the local TFA, they came after us.”

Happy Thanksgiving?!

By Thanksgiving, the number of people who had tested positive for COVID-19 in Collin County was around 25,000. That month, college President Neil Matkin sent a lengthy email to employees with the subject line, “College Update & Happy Thanksgiving!”

In its 22nd paragraph, after describing the success of a recent visit by accreditors and touting an employee-giving program, Matkin revealed that a faculty member had died of COVID-19.

Faculty were shocked. Some said they cried upon reading it. Later, they’d learn through a GoFundMe for funeral expenses that their deceased colleague was Iris Meda, a retired Texas nurse who felt compelled to return to a nursing classroom because of the pandemic. She felt that if she could teach “some of the basics, we could contain any virus,” her daughter told the Washington Post.

To faculty, it seemed like Meda’s death was an afterthought for Matkin. Many already thought he was dismissive of their safety concerns; the “Happy Thanksgiving” email solidified their thinking. The Chronicle of Higher Education wrote a story that said: “[The email] was emblematic of how Collin College leadership has neglected or negated faculty concerns throughout the pandemic. For months, instructors have told the president that they don’t feel protected by the institution’s plans and that he has been dismissive, said Audra Heaslip, a [faculty] council member who teaches humanities and literature.”

The Firings

College administrators have been reluctant to say that Jones and Heaslip were “fired.” But, in private meetings with their bosses in January, both were told—within hours of each other—that their employment at Collin College would end with the spring semester. Their terminations had nothing to do with their excellent teaching.

Jones was faulted for allowing Collin College’s name to appear on the TFA website, for criticizing the college’s reopening plan, and for once signing a petition to remove Confederate statues as “Suzanne Jones, Collin College professor.” Heaslip was accused of “bringing outside pressure” on Collin, she told Inside Higher Ed.

Their terminations quickly garnered national attention and condemnation. In a letter to Matkin, attorneys from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) wrote, “The First Amendment protects faculty members’ right to associate with a union and to publicly criticize their institutions’ public health policies.” In published op-eds, supporters wrote that the firings showed how much Matkin considers faculty to be disposable, and how safety and student learning were taking a back seat to profit.

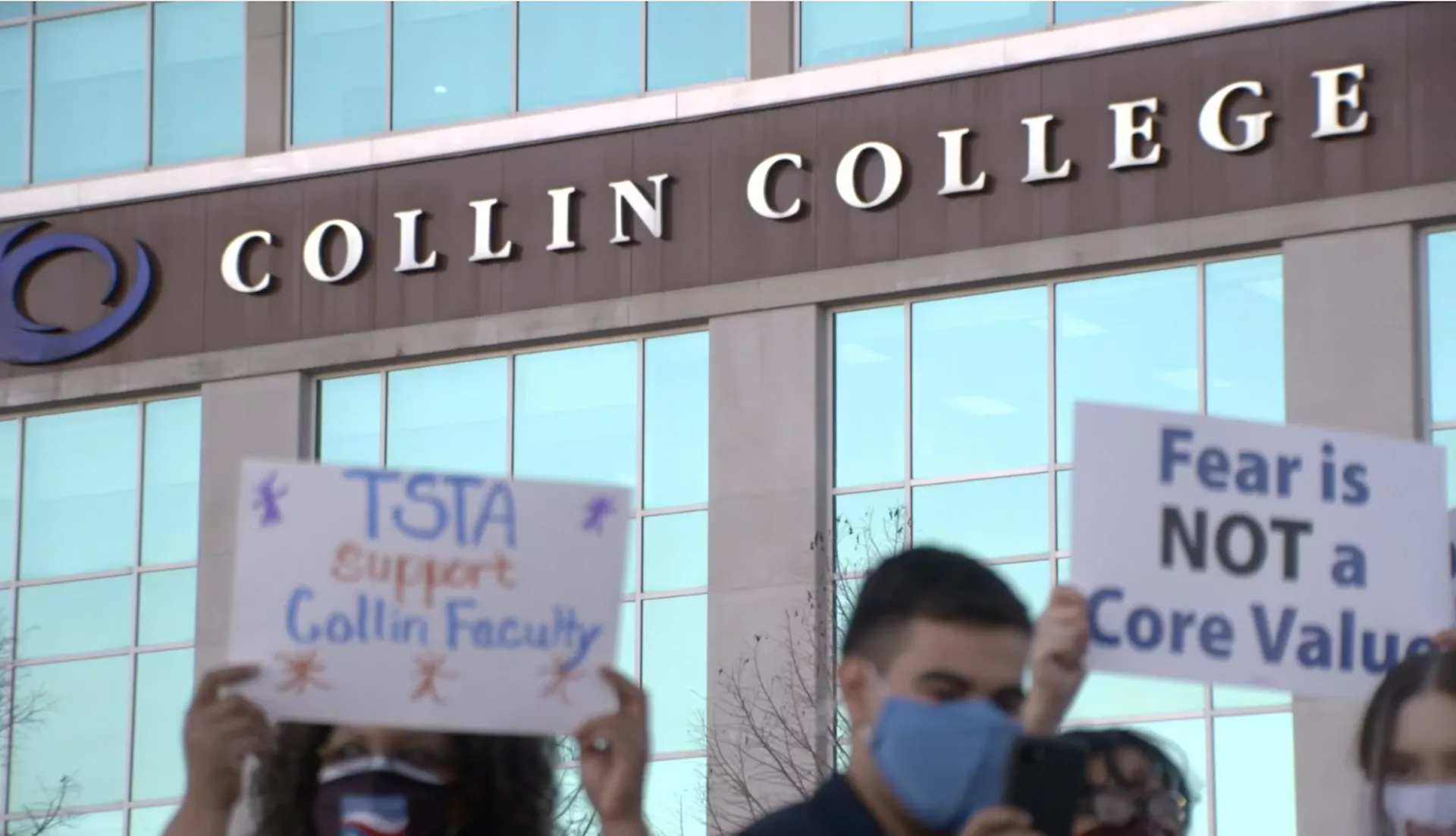

“Terminations and intimidation are driving away the excellent teachers responsible for so much of the student experience,” Helen Chang, a former Collin College teacher, told the Dallas Morning News during a spring demonstration.

Both Healsip and Jones are confident that their involvement with TFA/TSTA was a contributing reason to their firings. It’s likely not a coincidence that their employment was terminated on the very day that Jones, Heaslip and other local association members had scheduled their first meeting.

“I’m still in shock. I will never not be in shock,” says Jones. She grew up in Collin County, spent summers at the college as a student, and has taught at the college for 20 years. She loves her students. She loves her program.

“Everybody is like, just go get another job,” she says. “I don't want to look for a new job. I love this job!”

What’s Next?

By spring, the growth of COVID-19 cases in Collin County had slowed, as it did across the U.S. But the fever around Jones’ and Heaslip’s firings was unabated. Student supporters regularly showed up at the college’s board meetings. They picketed, talked to reporters, and signed petitions asking for the two professors’ immediate reinstatement.

“I know without a doubt I’m not the only student [Dr. Jones] has had an impact on,” Oney told Collin College board members in May. “If you look at her student evaluations, you’ll see so many of them praising her for making them better educators.”

[The educators'] terminations quickly garnered national attention and condemnation. In a letter to Matkin, attorneys from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) wrote, “The First Amendment protects faculty members’ right to associate with a union and to publicly criticize their institutions’ public health policies.”

Oney pointed out that, when Jones and Heaslip spoke up for safety, they were doing their jobs. “They know more about this school than you do,” Oney said. “They’re the ones who work with us, day in and day out. They know about our safety needs, and it’s their job to advocate for us. Firing Dr. Jones for doing this—her job as a great educator—is ridiculous.”

This spring, two of Collin’s board members called for a vote to reinstate Jones and Heaslip. “We’re not acting consistently with our core values of dignity, respect and integrity right now,” said board member Stacey Donald. But her motion was blocked by a majority of board members. Many Collin faculty also have reached out to Jones to say they don't agree with the college’s actions, says Jones. “But they know they’ll lose their jobs if they speak out,” she adds.

Currently, Jones and Heaslip have legal representation through TSTA and NEA, and Jones is hopeful her lawyers can help reinstate her.

After all of this, she still wants to work at Collin College.