Key Takeaways

- Since 2017, Baltimore Highlands Elementary School has been in the process of becoming a full-service community school.

- Community schools use local resources, including community agencies, colleges, and more, to meet the specific needs of their students and families.

- These partnerships have the power to transform student learning and offer opportunity to the entire community.

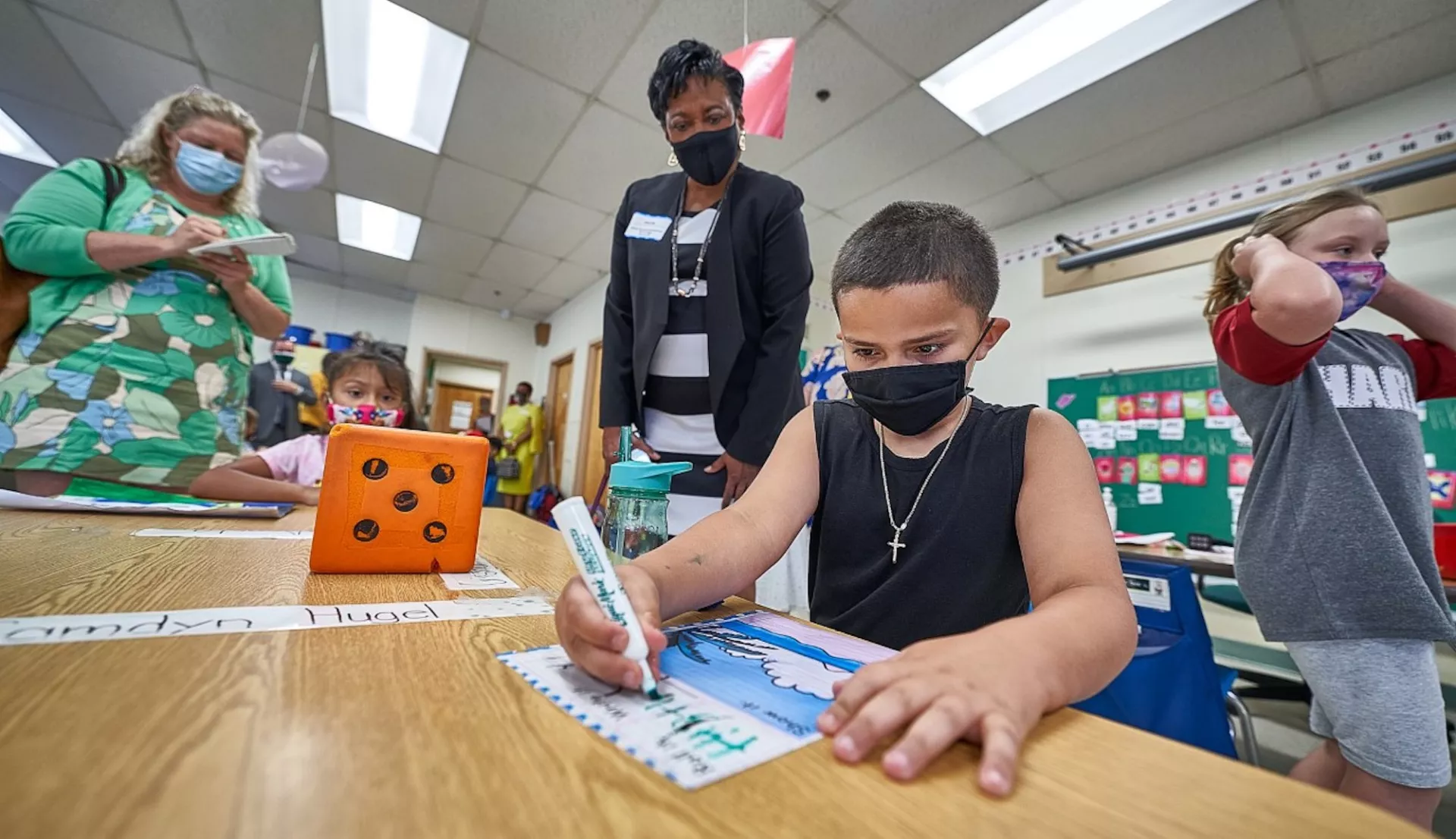

NEA President Becky Pringle poked her head into a kindergarten classroom at Baltimore Highlands Elementary School on Tuesday, delighting a sparkle-clad kindergartner named Clarisa as she unwrapped her Lunchables.

“Looks delicious!’ said Pringle.

What’s on the menu at Baltimore Highlands is delicious, indeed. Since 2017, the school has been in the process of becoming a full-service community school, dedicated to partnering with parents, families, and community organizations to meet the needs of its students. “Thank you for understanding,” Pringle told Baltimore Highlands educators, “that when we say every student will succeed, we mean every student.”

The work being done there—by Baltimore Highlands educators and their community partners—has the power to transform student learning and make every student successful. It also offers hope and opportunity to the entire community. This is why NEA has been fighting so hard for the expansion of community schools across the U.S., and why it supports efforts to put state and federal money into community schools’ development and expansion, including money from the federal American Rescue Plan.

“When I meet with the White House, when I meet with the Secretary of Education, I will tell them the story of Baltimore Highlands,” Pringle promised, “and the impact of what you’re doing will extend far.”

What Every Family Wants

Baltimore Highlands educators got hooked on the community school model four years ago, when some staff attended a NEA-sponsored community schools symposium in Texas. They returned to Maryland excited about what they could do for—and with—Highlands families as a community school, says Jill Savage, the school’s community school coordinator.

Their first step? In Texas, Savage and her colleagues learned they should do a “needs assessment,” talking with families and neighbors to figure out the needs of their community. While community schools can use community partnerships and resources to meet many various needs, NEA believes effective work is targeted to the specific needs of a community. (Want to learn more about community schools and their six pillars of practice, identified by NEA? Check out NEA resources on this topic.)

“It’s not about what [staff] wants,” said Savage. “It’s about what students and the community want and need.”

At Baltimore Highlands, Savage says that two assessments, done a few years apart, have pointed to the need for more career and college awareness among students; more literacy and English fluency among parents; and more after-school programs for the community. Last year, before the pandemic, many Baltimore Highlands parents took English language classes through the Community College of Baltimore County (CCBC), at Baltimore Highlands.

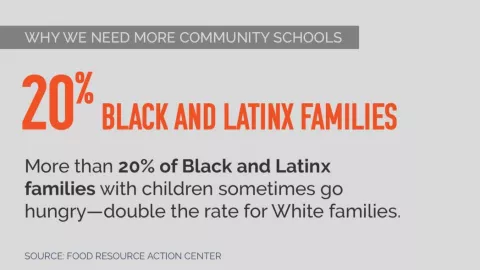

More than 80 percent of Baltimore Highlands students live below the federal poverty line; the largest demographic group is Hispanic students, who constitute about 35 percent of the school’s 550 students. Many are immigrant families, typically from El Salvador and other Central American countries, and Baltimore Highlands educators are working hard to connect with them.

“Families struggle around here,” acknowledges Savage, “but every family wants their kids to be successful.”

This is a Triumph

On Tuesday, Pringle was accompanied by Maryland State Education Association President Cheryl Bost, Teachers Association of Baltimore County President Cindy Sexton, and Jeannette Young, president of the Education Support Professionals of Baltimore County. All support the community schools model—and its expansion in Baltimore County and across Maryland.

By partnering with community agencies and organizations, like CCBC, the Y in Central Maryland, local food banks, and more, Baltimore Highlands educators are “meeting the social and emotional and academic needs of their students,” said Pringle. This is a model that can, and should, be everywhere.

The proof was apparent this past year, as the pandemic raged in Maryland. Parents lost their jobs. Families were struggling to eat, Savage recalls. And students were challenged by the switch to virtual education. But Baltimore Highlands educators are “accustomed to pivoting,” says Savage.

“We could have handed a list of food pantries to families, but that’s not very helpful,” says Savage. Instead, Baltimore Highlands put together an ambitious, drive-through food distribution program that served more than 250 families a day. They kept their community fed and healthy, and their students focused on learning.

“There has been a lot of tragedy this year,” Pringle told Baltimore Highlands educators. “But there also have been triumphs. What has happened at Baltimore Highlands is a triumph.”