It’s a well-known fact that many public school teachers enter the profession only to leave a short time later. The U.S. Census Bureau says teachers are leaving the profession at a rate that has continued to climb for the past three years.

First-grade teacher Michelle Usher stays. Currently in her eleventh year of teaching, and her second year at Brentfield Elementary School in Dallas, Texas, Usher says she considered the statistics on teachers who leave while attending last summer’s NEA Representative Assembly, and wondered, “Why aren’t we also talking about the people like me who stay?”

Her musings inspired this NEA Today article about the motivations that encourage Usher and other teachers to stay.

Usher was raised by a mom who this year entered her 39th year as an educator. But it was really her third-grade teacher, Robin Johnson—with whom Usher continues to maintain contact—who inspired her to teach.

While she was a student in Johnson’s class, Usher’s grand- mother died. “It was really hard on me,” she says. Johnson assured her they would weather Usher’s grief together.

Johnson’s support led Usher to understand early that teachers provide more than academic instruction. They also provide care—the lesson Usher says she most wants her students to receive: “I’m not just here to teach you something. I really care about you.”

Usher’s first teaching experience was in an Arkansas county where the number of students from families with low incomes was high. In the neighborhood surrounding her current school in Texas homes average $300,000, compared to a state-wide average of $185,000. The only difference between the two sets of students, says Usher, “is what their parents can provide.”

She says students enter school carrying with them an in- visible suitcase filled with whatever is going on in their lives, and they can’t set it aside. “Even though I don’t know what’s going on, I can help them unpack their suitcase.” At day’s end, she helps pack it back up, hoping that she has helped to make the contents a bit “fluffier and brighter,” she says.

And that’s why she remains. “I stay because I want to make change. Even when I started teaching, there were laws and policy procedures that didn’t fit with what is actually happening in the classroom. I could have left five years ago, but my drive is if I keep teaching in the classroom, [and] keep talking to parents, we can get the votes we need.”

She adds, “I think now, we are seeing what we decided earlier isn’t going to work. If I can impact students every day, teach them how government works, I am impacting what we will see in 20 years.”

Student Success

Jennie Campbell, a special education teacher at Pine Ridge Elementary School in Aurora, Colo., has a similar experience and agrees with Usher’s sentiment about how educators help to shape the future.

“For our kindergarteners today, the world is going to look completely different by the time they’re in twelfth grade,” says Campbell, who adds that educators strive to “help best meet the needs of our kids so that the world is accessible to all of them.”

Campbell is afifth-generation educator and says teaching runs in her blood. Her mom was a teacher of students with severe needs. Her grandmother was an English teacher whose mother and grandmother were one-room schoolhouse teachers. Campbell also has aunts and cousins who teach.

But when NEA Today asked Campbell why she decided to teach, she, like Usher, credited her third-grade teacher.

“There are always one or two teachers in your life who stand out because they did something to help you or they connected with you on a personal level,” Campbell says. “Ms. Harper was my inspiration [to become] a teacherT. here was something about her that made learning fun and magical.”

Campbell has been a special education teacher for 12 years, and has worked with students with severe autism and Down syndrome. Her student caseloads have been, at times, overwhelming. Yet, she remains in the classroom.

“Every kid is like a puzzle and I’m trying tofigure out what pieces I can give him or her to make learning a whole picture,” says Campbell, explaining that one of her students at the beginning of the year was reading 31 words a minute at grade level. Today, this student reads 85 words a minute.

“This is tremendous growth for a kiddo to read more uidly and to more accurately comprehend,” she says.

“And, to have the kids have the ability and the skills to be functional citizens within our world—however that may look—is why I’m still in it.”

Not every teacher comes from a family of educators or instantly recalls that one special teacher.

Goodbye Private Sector, Hello Public Education

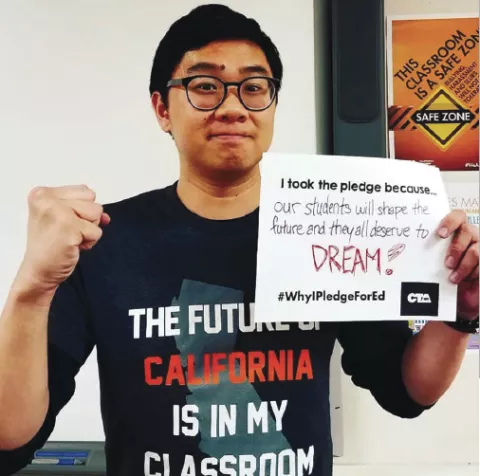

California’s Jayson Chang, who teaches tenth-grade world history and twelfth-grade government and economics at Santa Teresa High School in San Jose, Calif., held an unful- lfiling marketing position for two years before entering the classroom.

He recalls a staff meeting during which his manager explained how it was cheaper for someone in India to buy a TV from their U.S.-based company and have it shipped from their warehouse (also U.S. based) to India, than for the person to buy a TV from China and have it ship from China.

“China and India are right next to each other!” Chang recalls thinking that day. “It makes no sense to ship a TV back and forth across the Pacific. I made a comment about ‘That’s not good for the environment.’ My manager replied, ‘I’m here to sell TVs, not save the world.’ That’s when I knew I had to leave.”

After he resigned, Chang did some soul searching.

He reflected on his love of history—how, as a high school student, he often thought of wanting to teach history so other students, like him, would love the subject, too. He thought about his undergraduate studies, which focused on being a global citizen and making human connections. He thought about making a difference in the world.

In 2016, Chang stepped into the classroom recognizing that while all students may not end up loving history, they can at least understand its importance.

“Teaching history, and why it matters—especially now that the country is so divided—is where I can make an impact,” he says. “Students are our future and they can shape it as they see fit. It’s important to teach them about community.”

While he does enjoy his students’ “aha” moments, Chang finds it most rewarding when his graduated students come back to visit.

“It’s these moments that reinforce why I teach. Students share how I made a difference in their lives or how they used the lessons learned from my class in real-world siutations,” he explains. “!ese are the kinds of connections and the type of community experiences that get me pumped and ready to go the next day.”

From Volunteer to School Secretary

For JaTawn Robinson, a secretary at !omasville Heights Elementary in Atlanta, Ga., the power of community is strong.

Several years ago, Robinson was a frequent volunteer at her children’s school, Slater Elementary. Robinson was a lunch monitor, volunteer reader, and a field trip chaperone. She made copies and assisted in the office.

“Whatever needed to be done, I was there,” says the mother of three sons.