Key Takeaways

- During the pandemic, some kids had internet access. Others didn't. Some had parents at home to help. Others didn't. Equity needed to be considered.

- Even before the pandemic, many educators were rethinking homework. Research shows it stresses students and most of homework doesn't help learning.

- It still has its supporters, who point to homework's role in developing time management and organizational skills.

Over the last school year, as the pandemic raged and all schoolwork became homework, the debate over homework's purpose and merit returned in force.

“I didn’t want them to be on their computers all day,” says California middle-school teacher Beth Mendonca-Seufert. “If they didn’t complete an assignment, I didn’t harp on it. You don’t know what’s going on in their homes—maybe they’re trying to work while they’re watching their baby brother.”

During this time, what mattered more than homework, she decided, was that students came to class and that “they [felt] happy and supported.”

Last year, as pandemic-related stress skyrocketed and the lines between home and school blurred, many educators opted not to assign homework, they say. Parents were overwhelmed. Students needed a break from screens—if they had them. Equity was a concern. Some students had parents at home to help with tough assignments; others did not. Some had internet access; others none.

Now, as students and educators nationwide return to in-person learning across the country, some educators are ready for homework to return, too. Many others, however, say they hope the pandemic forced a reckoning—and that homework will never be the same.

Homework or Busywork?

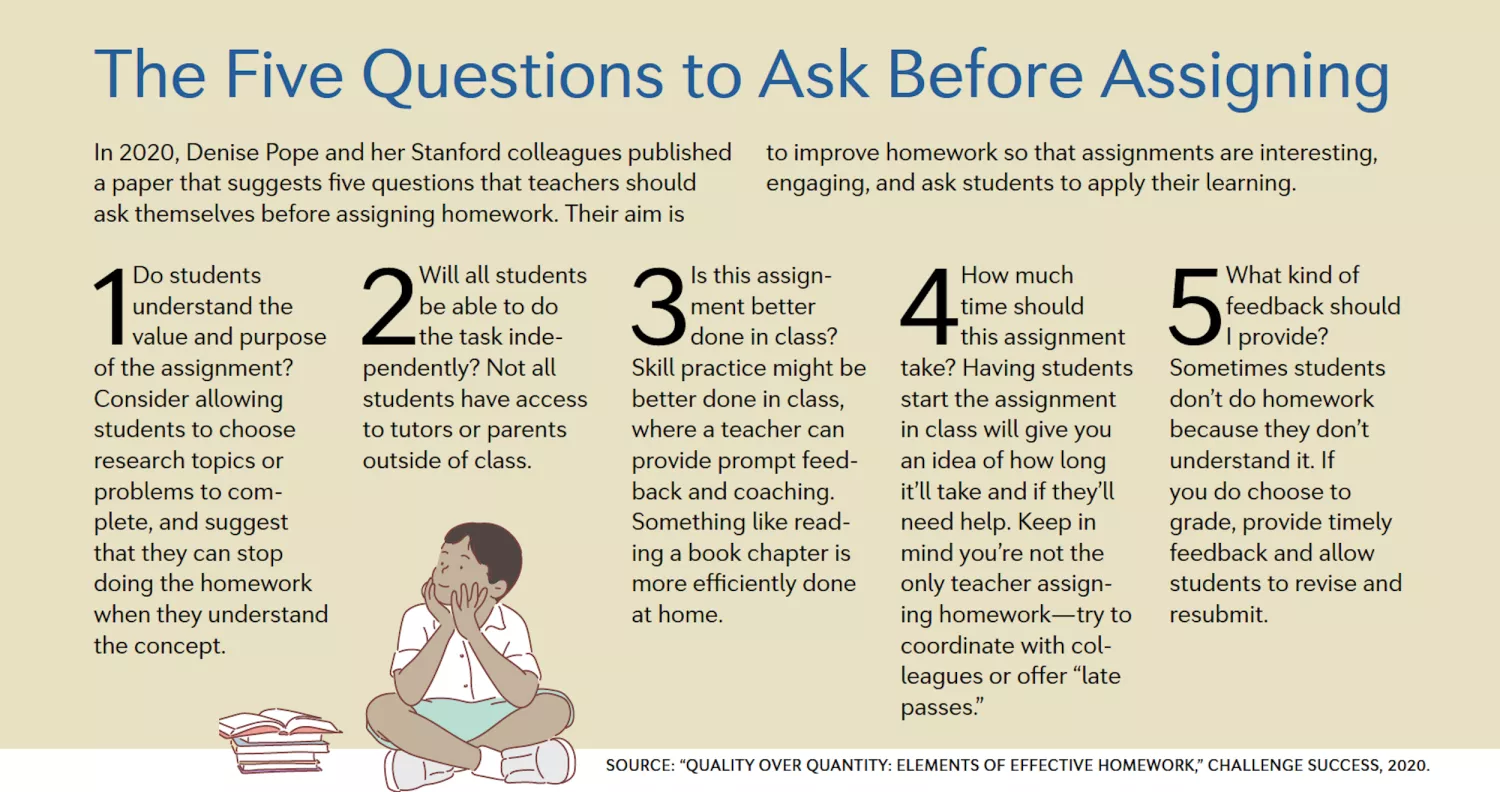

Stanford University’s Denise Pope, an expert in curriculum improvement and student engagement, has been studying homework for years. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, she found that homework usually does more harm than good, she says. For one thing, students list it among the top three stressors in their lives. For another, research shows homework—except for independent reading of books that students choose—doesn’t correlate with student success.

“When we ask students how meaningful their homework is, we often get the answer that it’s not,” says Pope.

Massachusetts third-grade teacher Kim Lopes agrees. The problem with most homework , she says, is that teachers must assign to the middle, she says. For advanced students, it’s busywork. For others, “it’s too hard, they need more support—and not everyone has a teacher at home.” Meanwhile, students and families could be using that time to unwind and recharge, she suggests.

“In my opinion, I think ‘practice’ should happen at school, where it can be supported by the professional in the room,” Lopes says. Lopes. For years, her students have had only two kinds of homework: basic math facts and an online, individualized reading and spelling program called Lexia Learning.

The pandemic reinforced what she has thought for years about homework—it’s stressful, inequitable, and unhelpful. Now, she hopes other educators will be more aware of these issues, too.

“I just hope they will be a little more empathetic," she says. “We’ve always had students whose parents don’t speak English, or students who don’t have internet. These problems have always existed, but the pandemic really put it in the front.”

Assignments with Impact

Even before the pandemic, shoe box dioramas and other elementary-age homework projects were fading in popularity. “They tend to need a lot of parent support and parents often are working,” says Pennsylvania fourth-grade teacher Camille Baker.

But that doesn’t stop Baker from assigning other kinds of homework. “I know I’m going to sound like I’m 95 years old,” says Baker, who has taught for 35 years, “but I think homework is a necessary part of school. I think it’s maligned because of the way it’s delivered. Its value depends on what’s assigned and how it’s assigned. It doesn’t have to be a traditional paper-and-pencil exercise.”

As students and educators nationwide return to in-person learning across the country, some educators are ready for homework to returns, too. Many others, however, say they hope the pandemic forced a reckoning—and that homework will never be the same.

Homework teaches organization and time management skills, as well as a sense of responsibility and self-advocacy, Baker says. If students can’t complete an assignment at home, she adds, "they need to go to school the next day and say I thought I understood this, but when I sat down to do it, I realized I didn’t.”

During the pandemic, Baker’s students kept up with at-home reading logs, which parents sign. But she was unable to assign her favorite homework project, in which students teach their parents a unit of study from class, like the water cycle. The work includes booking a time with their parents, drawing up a detailed lesson plan that allocates a specific number of minutes to teach the most important facts, and assessing parents’ learning.

“It’s a great way to engage parents and students,” she says. “I just wish people knew there were other ways to present homework.”