Key Takeaways

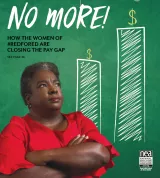

- Nationally, teachers are paid 21.4 percent less than similarly educated and experienced professionals.

- Across the economy, jobs dominated by women also pay less on average than those with higher proportions of men.

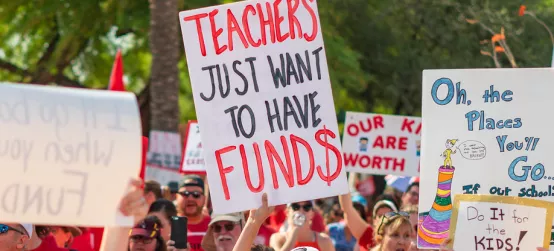

- The #RedForEd movement is about raising the quality of public education and bargaining for the common good.

Introduction

Rosa Jimenez, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, is a single mom who shares a bed with her daughter in a one-bedroom apartment in Los Angeles. She holds a bachelor’s and a master’s degree, but she’s still just scraping by in a city with one of the highest costs of living in the nation. Jimenez is a high school history teacher.

Fellow Angeleno Georgia Flowers Lee is a special education teacher at Saturn Elementary School in the gentrifying mid-city section. She can’t afford to live anywhere near her school, so she commutes about an hour each way from what she calls a “challenging” part of LA. She’s been an educator—her second career—for almost two decades but still struggles to make ends meet.

“You pay the bills, and you look at what’s left and you decide, ‘OK, what do I do without this month?’” Lee says.

Across the country in rural, western Pennsylvania, Missy Brant teaches kindergarten. She says there are teachers right in her backyard who earn just over the minimum wage. The starting teacher salary in Pennsylvania is $18,500 and has been since 1989, when Brant was just 8 years old and thinking of becoming a teacher like her mom. It never occurred to her that educators would be worse off now than they were then.

Jimenez, Flowers Lee, and Brant aren’t alone. Across the nation, teachers—most of them women—are underpaid and struggling. Their growing frustration has fueled a nationwide movement called #RedForEd that demands professional pay for professional work.

Professions dominated by women have lower pay, but even within the profession there is discrimination. Music educator Nancy Flanagan had to fight for her position as a band leader at a Michigan middle school. Leading a band held prestige, like coaching the football team, and the positions were given to men. After finally getting the position, she didn’t earn as much as her male peers.

“I went on job interviews where my fitness and stamina were questioned. One principal said he had no intention of hiring me because he was looking for a man for the job. He just wanted to meet the girl who thought she could handle his high school band,” Flanagan recalls.

Even her own high school band director, whom she’d admired and assisted from freshman to senior year, told her he didn’t believe in “lady band directors” and that she’d be better off as an elementary music educator. When she did get a job in the 1970s—one she kept for 30 years—she was one of the only women in an exclusive men’s club. There were seven female band directors in a state with 500-plus school districts. She was often belittled, underestimated, or ignored. Not surprisingly, she never earned as much as her male counterparts. Though she’s retired, she is a vocal proponent of higher salaries and respect for educators.

Four different women. One strikingly common experience: They all entered a profession where women are underpaid and undervalued. But that lack of equity has these women and legions more seeing red.

Bits of History Repeating

Margaret Haley was a sixth-grade teacher in the stockyards district of Chicago, the poorest part of the city. With a class of 50, sometimes 60 students, she had to follow a rigid curriculum developed by bureaucrats who’d never set foot in her classroom. She taught there for 16 years, with no signs of the community rising from its crushing poverty. She realized it was up to teachers to push for change in the community and in the schools.

So she joined the teachers union. She spoke out about the treatment of teachers as “automatons” and against the policy of paying high school teachers (mostly men) more than other teachers. She became a union activist, then leader, giving up her teaching position to work on union issues full time. She fought for higher salaries, pensions, tenure, and better learning conditions in the schools. She called out corporations for not paying their share of taxes, depriving cities and towns of much-needed funds for schools.

Then she rose to the national level to become the first woman allowed to speak at the NEA Convention, delivering the famous speech, “Why Teachers Should Organize.”

The year was 1904.

She argued that collective bargaining is critical to professionalized teaching and that “there is no possible conflict between the interest of the child and the interest of the teacher.”

More than 100 years later and we’re still fighting the same battles. Why? The reason is simple and can be explained in one word: Sexism.

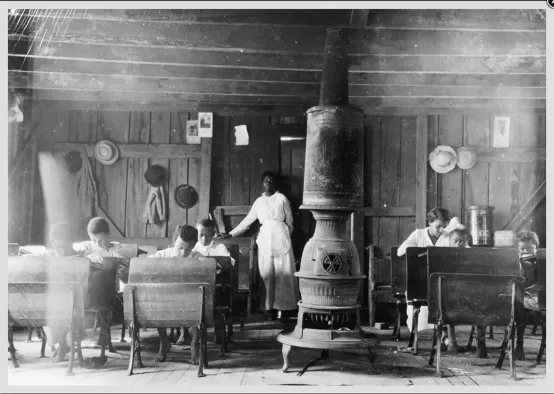

Gender stereotypes push women toward lower-paying, care-focused, or service-oriented jobs—like teachers, nurses, and social workers. And then they get paid less because they’re doing “women’s work.”

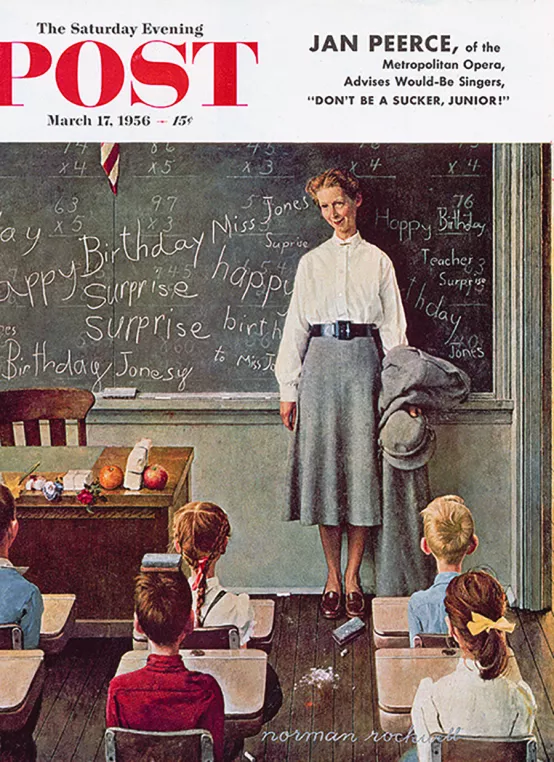

It’s a holdover from the outdated belief system that women are better suited for service labor because of feminine, domestic, and nurturing roles they performed in the home for centuries without any compensation. When performed in the paid labor force, they’re devalued.

Women in Teaching

Women in Teaching

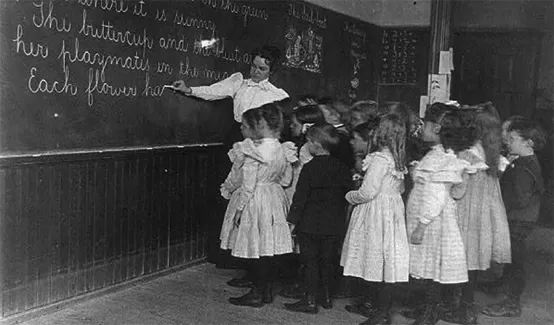

Teaching Becomes a Women's Profession

Underpaid and Overworked

Gender Stereotypes of the Teaching Profession

An Extension of Mothering

A New Law

A Nation at Risk

NCLB

Great Recession Budget Cuts

RedforEd

The Female Pay Penalty

Nationally, teachers are paid 21.4 percent less than similarly educated and experienced professionals. Susan Moore Johnson, a professor at Harvard, and expert in teacher policy, calls the pay penalty “the hidden subsidy of public education.” Because education has been and continues to be a profession dominated by women, districts can pay less to staff their schools.

Across the economy, jobs dominated by women also pay less on average than those with higher proportions of men, and enjoy less prestige as well.

At the end of the 19th century, secretaries were men. The position was considered an apprenticeship; a learning step before the men eventually took over the business. When women became secretaries, the position was devalued, and the opportunity for growth or promotion dissolved.

According to a study, “Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950–2000 U.S. Census Data,” by Asaf Levanon and Paula England of Stanford University and Paul Allison of the University of Pennsylvania, when women moved into occupations in large numbers, those jobs began paying less even after controlling for education, work experience, skills, race, and geography. The reverse was true when a job attracted more men, like computer programming, which used to be considered a menial job done by women. When male programmers began to outnumber female ones, the job began paying more and gained prestige.

When you break it out for women of color, the gender pay gap is even worse. Overall, women are paid 80 cents for every dollar paid to men. Black women earn just 61 cents, Native American women 58 cents and Latinas just 53 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families.

I Didn't Go Into Teaching for the Money

It’s likely that every educator has thought or uttered the phrase, “I didn’t go into it for the money.” It’s certainly a job offering many priceless rewards. It’s also a profession that serves children and it would be selfish—even greedy— to ask for more money when your whole reason for being there is for the kids. Or, so those who would cut education funding would have teachers believe. Unfortunately, fulfillment from serving children doesn’t pay the bills.

“They prey on our emotions,” says Pennsylvania kindergarten teacher Missy Brant. “This is for the kids, they say, so as a highly educated professional with four and a half years of graduate work and advanced degrees, I’ll be happy just sitting back and taking it while I work four jobs to pay my mortgage, because I didn’t go into it for the money?”

Brant says she is much more a Rosie the Riveter than a Betty Crocker, but there was a time, she admits, when even she internalized gender stereotypes.

“I used to worry that I’d be the last teacher to have ‘Miss’ in front of my name,” she says.

One by one her colleagues got married and started families and wondered aloud why Brant didn’t do the same, as if she should follow all women down the one path society has agreed is the best.

“Don’t you want to be a mom?” Brant was continually asked by her well-meaning colleagues.

“No, I don’t, because that’s not my path. I’m a union leader and this is my passion, this is my baby.”

I am Woman. Hear Mama Bear Roar.

But Brant also points out that the feminization of the teaching force can cut both ways. Gender roles dictate that women are more nurturing, but they also dictate that they protect their young. She says she’s never met an educator who didn’t call her students “her kids.” And when budget cuts threaten their kids, educators’ protective instincts can become a powerful force.

“When you go after our kids, we will go mama bear on you!”

The #RedForEd movement is a collective mama bear roar.

“Our critics say walkouts hurt the kids,” says Brant. “What really hurts the kids are dilapidated buildings with no nurse on staff, no art or music, and overcrowded classrooms where underpaid and burned out teachers can’t offer the time and attention they know their kids need.”

The #RedForEd movement isn’t about raising salaries, it’s about raising the quality of public education and bargaining for the common good.

“Society demands that we are caretakers of the community, and educators are negotiating for benefits on behalf of the full community,” says Lane Windham, associate director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor and co-director of WILL Empower (Women Innovating Labor Leadership).

When Rosie Jimenez and Georgia Flowers Lee walked the line in Los Angeles they weren’t just fighting for higher salaries but also for racial justice, pushing for immigration rights and against random searches of students at school. When the community saw them fighting for their issues and giving voice to their concerns, they came out to support them. They hosted sign making parties, they plastered their support across social media, and they stood out with them on the picket line in the cold mid-January rain.

Get more from