Key Takeaways

- Since its inception, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, which is supposed to forgive the student debt of teachers and other public-service workers after 10 years of service, has rejected 98 percent of applicants.

- Meanwhile, educators are drowning in student debt. They can't afford to buy homes, save for retirement, or send their own children to college. The effects on the profession have been huge: Who would want to take on this kind of debt to do this job?

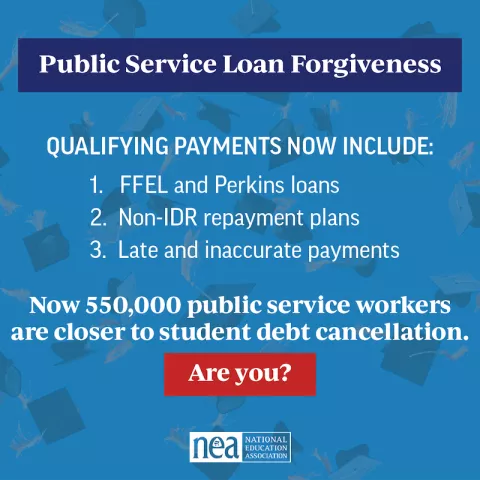

- The overhaul expands the program to older loans, such as FFEL loans, and also enables late payments to count toward PSLF. More than a half-million borrowers will move closer to loan forgiveness, and 22,000 will become immediately eligible.

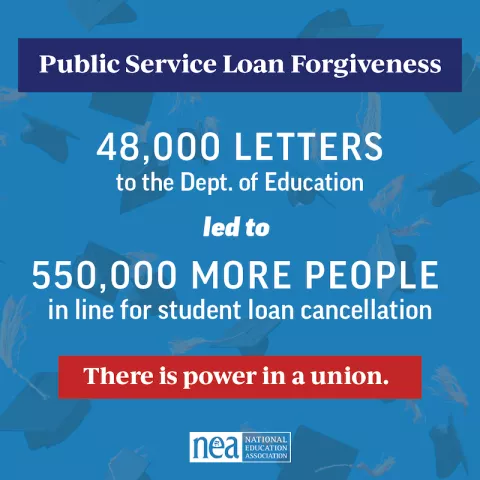

After hearing from 168,000 NEA members about the failures of Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), the Biden-Harris administration announced today an overhaul of the broken program.

The changes to PSLF—a government program that is supposed to forgive the student debt of educators and other public-service workers who have served their community for at least 10 years—will mean 550,000 borrowers will move significantly closer to student debt forgiveness, including 22,000 who are immediately eligible.

NEA praised the changes as “a welcome step toward keeping the promise of PSLF and cancelling the student debt of every educator who has served their commitment to their communities." The Biden-Harris administration should be commended for keeping its promise to educators, says NEA President Becky Pringle.

But these changes likely wouldn't have happened “without the activism of NEA members," she stressed. In just the last two months, NEA members sent 48,000 emails to Education Secretary Miguel Cardona about the many ways PSLF has failed its promises.

Learn more about these changes at an expert briefing tomorrow, Thursday at 7 pm ET. You can also catch the recording of our Town Hall with U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona:

What’s New

The changes announced by Cardona include a broad expansion of the types of payments that count toward PSLF. Originally, the program was limited to simply this: On-time payments toward federal Direct Loans through Income-Driven Repayment (IDR).

Now, borrowers can also count payments that they’ve made on older federal loans, including Perkins and Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program loans, as well as non-IDR payments and late payments. Borrowers must apply through a limited waiver, available through Oct. 31, 2022.

An estimated 550,000 public-service workers will see their progress toward PSLF grow, by an average of 23 monthly payments. This includes 22,000 borrowers who will immediately become eligible, without having to do anything, totaling $1.74 billion in forgiveness. Another 27,000 borrowers could potentially receive $2.82 billion in forgiveness, if they certify additional periods of employment.

"If you give 10 years in service to the community, you should have your loans forgiven. It's as simple as that," said Cardona, during a call Wednesday night with Pringle and AFT President Randi Weingarten. "We’re going to fix whatever issues there are… It’s not going to happen overnight, but we’re committed to making this process simpler. You deserve it."

Meet Merrie Wolf

The borrowers who see relief through today’s PSLF overhaul likely will include educators like Merrie Wolf, an award-winning Oklahoma math teacher who began teaching in the late ‘90s, after 20-plus years in the optical industry. Wolf borrowed from the federal government to pay for a master’s degree.

For more than 12 years, Navient—the big bank that bought her loans and received her payments—told Wolf that she was on track for PSLF. Never did they tell her the truth, which is that she needed to consolidate her loans into federal Direct Loans through a different bank. Until today, Direct Loans have been the only loans that qualify for PSLF, and FedLoan—not Navient—was hired by the government to manage PSLF.

The problems became clear when Wolf applied for PSLF in 2019. None of her payments with Navient, which added up to more than $37,000 over 12 years, counted toward PSLF. With little choice, in August 2019, she transferred her balance to FedLoan and made the first of 120 payments toward PSLF, restarting the clock for another 10 years of payments.

Wolf’s original loan amount was $33,000. After paying on it for more than decade, she now owes $49,552.18.

If nothing was done to help educators like Wolf, she would be eligible for PSLF in 2030, at the age of 75.

A Growing Burden

And it’s not just Wolf.

Recent NEA research shows that nearly half of current educators borrowed to pay for college—and they still owe $58,700, on average. Among them, one in seven still owes more than $105,000.

It’s worse for younger educators, who are forced to cover the skyrocketing cost of college (nearly half borrowed more than $65,000), and for educators of color, who often have been excluded from typical forms of generational wealth, due to racism in housing and banking systems. More than half of Black educators (56%) have taken out student loans—with an average initial amount of $68,300—compared to 44 percent of White educators, who borrowed $54,300 on average.

On the one hand, this level of student debt is a financial burden, making it difficult for younger educators to buy homes and older educators to save for retirement. On the other, it’s also a mental burden. Four in 10 educators with unpaid student debt told NEA it has affected their physical, mental and emotional well-being.

Carolyn Hawkins, a 64-year-old Georgia kindergarten teacher, pays $703 a month for her student debt, which totals more than her house mortgage. For her a world without student debt is a dream.

“I’d feel like a normal person,” she says.

Broken Beyond Repair

Here’s how PSLF was supposed to work: Public-service workers, such as teachers and firefighters, make payments toward their student loans for 10 years—and then the remaining debt is forgiven.

In reality, "It's been like an American Gladiator obstacle course," says Under Secretary of Education James Kvaal.

Ninety-eight percent of PSLF applicants have been denied by the federal government for having the wrong kind of loans or for other reasons that don’t make sense. Many, like Wolf, were never told by their loan servicers that they didn’t have the right kind of loans or repayment plans. Many have had payments that were a day late or a few pennies short not count. Thousands of educators were denied because the government mistakenly failed to certify their employment—in public education—as public service.

“I feel like I did everything I was supposed to do—I worked in special education, I worked for Title I schools,” says Rhode Islander Pat Giarruso, who still owes around $20,000 on her student loans—even in retirement.

And for every applicant denied, countless others have never applied for PSLF because of misinformation by the previous administration, or because of PSLF’s overly rigid requirements.

Under Pressure

Fixing PSLF has been a priority for the Biden administration—and they have faced an increasing amount of pressure from NEA and other advocacy groups to do it before the COVID-related suspension of student-loan repayment ends on January 31.

In April, NEA led a coalition of 18 unions, representing more than 10 million public-service workers, in calling on Cardona to cancel the unpaid debt of public-service workers who have served their communities for at least 10 years. The unions also asked Cardona to audit the records of every potentially eligible borrower, including part-time faculty who don’t currently qualify.

The problem with PSLF—and its unfulfilled promise to educators—isn’t just that so many teachers and education support professionals are struggling with debt. It’s that, and also that it unaffordable for young people to become teachers.

"These reliefs are especially important to educators of color," says Pringle. While everybody should be able to pursue their dreams of higher education, regardless of what they look like or where they come from, the fact is that "generational poverty impacts these communities… They borrow more. They pay more. [Today's actions] will help us recruit more educators across the board, but especially educators of color."