Her father became incarcerated when she was 2 years old. Her family lost their sole breadwinner and were thrust into poverty and homelessness.

“I did my very best to cover up that shame by being the very best person I could be, being the best student, trying to excel in everything, and thought that would hide it all,” Collins says. “I didn’t have to really face it until my own son became incarcerated.”

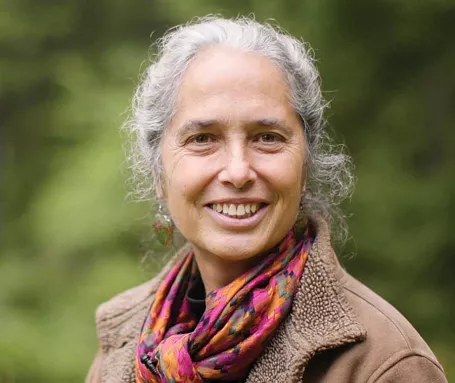

Collins and her husband, who live in Wilton, Maine, adopted their son when he was 8 years old. What he experienced before that, Collins prefers not to share.

“The trauma will follow him forever,” she says.

Collins felt she could no longer hide from the harsh reality of the prison system. She needed to work to change it. In 2014, Collins and her husband began volunteering in prisoner advocacy organizations.

“When you look at incarceration, it is a very inhumane process that does more harm than good,” she says. “It’s not a pretty picture.”

Today, Collins is the assistant director of the Maine Prisoner Advocacy Coalition. She works to educate the public—including presentations to the Maine Education Association (MEA)-Retired Annual Conference as well as local chapters of MEA-Retired—about what actually happens when people are incarcerated.

“People sometimes think that their loved one will finally get the help they need,” she shares. “In reality, … in a trauma-filled prison setting, people are much more likely to get worse.”

Collins also helps organize exhibits of artwork by incarcerated people. The exhibits have been “really eye-opening for the public,” she says.

Educators play a powerful role

Schools play a critical role in either diverting students from the incarceration system or pushing them into it, Collins says.

“We need to make sure we do not misinterpret a child’s misbehavior as ‘criminal activity,’” she explains. “Lots of kids are too young to voice their trauma and have no other way to express it but through their behavior.”

When students are punished instead of supported, Collins says, “we set them up for failure, and we set them up for incarceration.”

Other institutional barriers such as learning disabilities, mental illness, and lack of health care can increase a person’s chances of being incarcerated by up to seven times, she adds. Students with an incarcerated parent also face extra difficulties, as Collins knows from personal experience.

“As teachers, we have one of the most important jobs in the world,” she says. “We can identify those kids who most need us and make sure they have the hope and help that will protect them.”

For more member stories, go to nea.org/member-spotlight, or submit the name of a retired educator you’d like to see featured at nea.org/submit-member-spotlight.