Key Takeaways

- Student teachers, many of whom are under financial stress, are required to do the work of a full-time educator without pay.

- Decades ago, it was common for college students to take on unpaid internships. Over time, compensation has been added to many professional programs—except teaching.

- Learn how three Aspiring Educators are networking with their peers and lobbying lawmakers to pass legislation that would offer pay to student teachers.

Student teaching is one of the most important experiences in your education major. It’s the last stretch of road where you put into practice everything you’ve learned in the past few years before graduating and taking charge of your first classroom.

For many, it also brings financial stress, given that student teaching positions are usually unpaid. That’s why many NEA Aspiring Educators (AE) are advocating for pay for student teachers.

A LESS THAN PERFECT SYSTEM

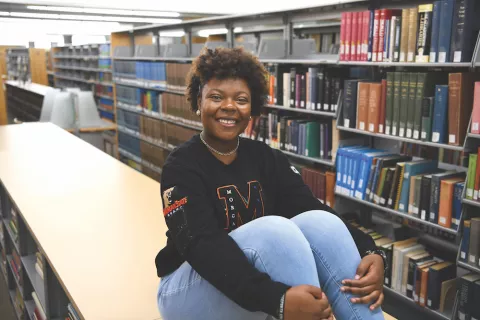

Jailyn Bridgeforth is a senior at Morgan State University, in Baltimore, Md., majoring in elementary education. Originally from Georgia, she comes from a family of teachers (including her grandmother, mom, and brother) and is excited about her future profession.

Bridgeforth says she is most excited about “being a support system for students who might not have healthy role models at home.”

What she’s less excited about is not getting paid as a student teacher. “It’s bonkers,” she says.

Bonkers is exactly the right word to describe a system that requires students to do the work of full-time educators without pay. Some professors advise candidates not to get paid jobs during their internships because the internships are so demanding of time and energy. It’s hard to succeed if they also must work. Bridgeforth, however, needs to earn money.

“I do everything on my own,” she says, from keeping her own apartment to paying for tuition. Juggling her internship, campus classes, and her job is difficult.

“Teaching is the thing I was called to do, ... the only thing I’ve ever had dreams of doing, and it feels like it’s beating me down. It’s hard,” she says.

PAID INTERNSHIPS WANTED

One day last year, Bridgeforth found herself on the phone with a Maryland State Education Association organizer. Bridgeforth was rightfully irritated about not getting paid. The organizer asked one question: “Do you want to change it?”

The question was enough to move Bridgeforth to action, and she is leading efforts to change this equation in Maryland. Additional initiatives are percolating in other states, centering on three problems: Unpaid internships; lack of transportation resources; and too little control over where student teaching candidates are placed.

In Bridgeforth’s experience—and she heard the same from other AE members during a virtual listening tour in August 2022—candidates are often told of their field placement just a week before they start.

“You don’t know anything about the school. It doesn’t matter how far it is. It doesn’t matter if it’s the kind of school culture you want to learn about,” she says. “They just tell you to show up.”

She’s even heard from Aspiring Educators who are spending hundreds of dollars on Uber rides to get to their unpaid placements.

THE STAKES ARE HIGH

Jonathan “Jonny” Otero is a junior at Northern Arizona University, in Flagstaff. He’s majoring in elementary and special education, and while his student teaching experience doesn’t start until next year, he’s already concerned.

“I’m worried that nothing’s going to change and mi gente [my people] won’t go into education,” he says. “I’m worried that this system will continue to oppress BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] and LGBTQ+ educators.”

His concerns are well founded. Last year, an NEA survey found that a staggering 55 percent of educators were thinking of leaving the profession earlier than planned. The percentage was higher among Black (62%) and Latino (59%) educators, who are already underrepresented in the teaching profession.

“When we talk about the ‘teacher shortage,’ we’ve never had one,” Otero says. “What we have is a lack of respect for educators and for our future.”

And so, he’s working to organize political actions in Flagstaff and insert BIPOC voices into the conversation.

PAYMENT IS LONG OVERDUE

Decades ago, it was common for college students to take on unpaid internships. Over time, however, compensation has been added to many professional programs.

“Teaching just hasn’t done that,” says Jonathan Frey, a student at Southern Utah University, in Cedar City.

Future doctors have a long history of being paid for their internships. Meanwhile, the education profession has underpaid its educators for years, making it financially out of reach for many candidates to pursue teaching without taking on an extra job during college.

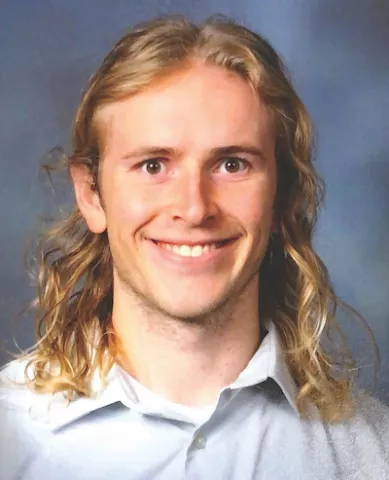

Frey, who is a business education and accounting major, graduates in spring 2024 and plans to become a career technical education teacher.

He’s two semesters shy of starting student teaching and is preparing now to soften the blow of lost income.

“It’s going to take a hit on me and my wife,” he says. “We’ve preemptively set ourselves up where we’re renting out extra rooms in our townhome. I’m working two jobs right now, since I won’t be able to work either of them when I student teach. It’s a little scary.”

Frey knows he’s in a better situation than some of his peers, which is why his big push right now is to increase awareness around this issue, to grow AE membership, and then to encourage his fellow Aspiring Educators to contact their public officials.

A BETTER WAY IS POSSIBLE

Back in Maryland, Bridgeforth is working to get a state law passed that would guarantee funding for colleges to go toward paying student teachers. Bridgeforth explains that in her state, teacher candidates are required to student teach for 120 days before earning a teaching certification. By 2024, that number increases to 180 days.

“We’re looking at government officials to recognize those days should be paid,” she says.

For future teachers and across the profession, better pay is key to recruiting and retaining educators. “Candidates experience greater success when they receive sufficient financial support to allow them to focus on their student teaching,” says Blake West, a senior policy analyst with NEA’s Center for Professional Excellence and Student Learning.

It’s not unheard of either.

Some universities offer stipends through teacher residency programs. In Texas, for example, a group of education majors at Texas State University in San Marcos were awarded $20,000 each. Other residency models are connected to a particular school district trying to solve specific needs, such as the Boston Teacher Residency program, which focuses on STEM teachers.

NEA has long championed residency programs that offer intensive, yearlong student teaching experiences with a mentor teacher. These programs offer tuition assistance, to help attract new teachers, and provide ongoing support and a sense of community to retain educators through their first years on the job.

Bridgeforth is set to graduate in a couple of months, and while she may not benefit from her efforts now, she hopes her work today will help other future teachers.

“I’ve met so many Aspiring Educators who truly have a fire for teaching,” she says. “Knowing what’s coming for them is what pushes me to do more, so that they don’t have to work the midnight shift to survive or run themselves ragged to make a buck.”