On February 13, 2023, Reagan Williams finished a night class and went to an Aspiring Educators of Michigan State fundraiser at Raising Cane’s Chicken Fingers, a popular campus gathering place. It was a normal Monday.

“Everything was going great, and spring break was on the horizon,” says Williams, a senior elementary education major at Michigan State University (MSU) and president of her Aspiring Educators (AE) chapter.

But in a matter of minutes, everything changed.

“I was right across the street from where the first shots took place,” she says. “I saw people running from the building, but I didn’t think anything of it until I saw tens on tens of police cars pull up.”

Williams then found a police officer to escort her from the restaurant.

What happened?

A gunman had started firing inside two campus buildings. Three students were killed and five others were injured before the gunman fatally shot himself.

“It was just one of those moments I never thought would happen to me,” Williams says. “Even though I was witnessing people across the street fighting for their lives, I knew the first thing I had to do was take care of myself, which was a hard realization.”

The Fear Spreads

In a classroom across campus, MSU second-year student Jacinta Henry was in a club meeting with her friends. When they found out an active shooter was on campus, they ducked under tables and waited for hours in the dark.

“The club is a safe place for me. It’s a discussion place for different ideas and a [multiracial] learning community,” says Henry, who is studying interdisciplinary social studies for secondary education. “So it was insane to have my safe space turned into a place where I wasn’t sure if I was going to survive. … It was a sense of terror that I had never experienced, and I hope I never do again.”

Sophomore Jessica Steller was also on campus when the violence took place. The elementary education major had spent the day with her boyfriend and friends. She, too, had attended the AE fundraiser before returning to her dorm to watch The Bachelor with friends.

That’s when they heard the sirens. Then she received a text from a friend, a call from her mom, and an MSU email, all saying the same thing—there was an active shooter on campus.

“Three girls went to barricade the door, I went to barricade the window,” Steller recalls.

“We all laid on the ground with the lights off. It was such a scary moment.”

None of the students had to stop to figure out what to do. They had been training for this since kindergarten.

“We know what to do, we know how to hide, we know how to be quiet, which is super scary, but we were prepared for it,” she says.

Quote byJessica Steller , sophomore student

Growing Up in an Era of Mass Shootings

In 2022, the U.S. had the most school shootings ever in one year, according to the K–12 School Shooting Database.

Today’s students don’t need statistics to tell them this is true. They have lived it.

One of those students is Czaria Cole, a junior studying elementary education and Spanish at Grambling State University, in Louisiana. During homecoming celebrations in October 2021, two shootings took place on her campus within four days of each other.

On October 13, an 18-year-old gunman started shooting in front of the student union, killing one person and injuring three others.

On October 17, a second shooting took place in a quad area, killing one person and injuring seven.

Cole did not witness the shootings firsthand. Tweets and emergency messages from her school alerted her to what was happening. But the experience was all-too familiar.

“Growing up, I’ve had other situations where we heard shootings outside where we lived,” says Cole, who is from Texas.

Like many other college students today, she has grown up with the fear of mass shootings.

Gun Laws Work

“Legislators often act like this is a rocket-science problem that doesn’t have a simple answer to it. But it has a pretty easy answer,” says Alana Rigby, who graduated from Florida State University in May 2023, with a master’s in curriculum and instruction.

“If we were to ban assault rifles, we would see the risk of shootings decrease severely, which we did see when the ban on assault rifles did exist,” she explains, referring to the federal ban that was in place from 1994 – 2004.

Rigby is a relentless advocate for safe schools. In January 2023, she traveled to NEA headquarters, in Washington, D.C., with a group of AE members.

They joined a gathering of educators from across the country—including local union presidents, teachers, school support staff, and others—to review NEA’s policy recommendations on gun violence.

“It was very inspiring,” Rigby says. The AE team helped to revamp NEA’s School Crisis Guide, adding plans that address emergencies and recovery from tragedies.

Quote byAlana Rigby, Florida State University graduate

Find more ways to create change as well as NEA resources on responding to gun violence at www.nea.org/GunViolence.

How Do We Make Schools Safer?

The sheer magnitude of the gun violence problem can be overwhelming. There is not one solution, but many that collectively can stop the killing. These are a few of the strategies that have been proven to make a real impact:

- Safe storage laws, which require gun owners to lock up their firearms, are key to reversing current trends. The weapons used in nearly 70 percent of gun-related incidents in schools were taken from the home of a friend or relative, according to the RAND Corporation. These laws are among the most effective ways to reduce violent crime, suicide, and accidental death.

- Red flag laws—which make it possible to prevent a person in crisis from accessing guns—have been proven to work. Also, programs that teach educators and older students to identify and report signs of trouble are showing promise.

Why does this work? Because more than 40 percent of school shooters are former students, and nearly all shared threatening messages or images before the incidents, reports Everytown for Gun Safety.

Case in point: The Say Something training program, offered by Sandy Hook Promise, has managed 2,700 interventions. At least nine credible school shooting plots were averted

and 321 lives were saved.

Communities can find common ground to make schools safer. More than 60 percent of U.S. gun owners favor laws that are shown to reduce gun injuries, according to the gun violence prevention group 97 percent.

The data shows that these sensible approaches work to reduce gun violence. That’s why, Williams says, it’s important for future educators to demand action and change, and to work to make schools safe for all students.

Three Ways You Can Make a Difference!

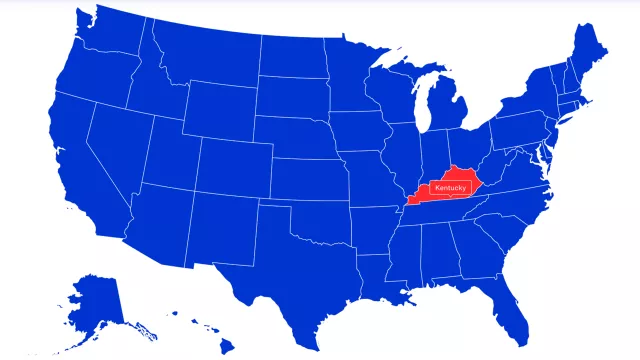

Advocate for gun safety laws in your state

Push Congress to Act

Help Make Your School Safer

Ensuring Safe School Communities

Get more from