Key Takeaways

- Schools are set to open as anxiety surges like the Delta variant. But there are ways to help students and educators manage their stress.

- Social and emotional learning (SEL) must take priority over academics so that stress doesn't interfere with learning (or teaching).

- Work with your state to fund more school mental health counselors and learn SEL strategies at nea.org/SEL.

This year, back to school is anything but “back to normal.” As we return to our classrooms in the wake of the pandemic, many are wondering if school will ever be the same again. But when it comes to social and emotional learning (SEL), that’s actually a good thing.

Trauma is an effective teacher. It taught us what matters most: connection before curriculum; emotions over assessments; well-being over workload. These aren’t new lessons, but the global pandemic reminded us what research has long shown: SEL is inextricably tied to academic success.

When many schools reopened to in-person or hybrid learning during the last school year, it was clear to educators that mental health had to be addressed before anything else. That hasn’t changed.

“Students can’t learn when they’re stressed,” says NEA President Becky Pringle. “School mental health professionals and all educators have to listen to them, talk to them, and understand how they are experiencing this world in this moment, which is different from our experiences. Educators have to work together to address stress and trauma before we can get to a place to learn.”

With school counselors facing overwhelming caseloads and a skyrocketing number of students in need, some schools are recognizing the power of SEL and providing mental health supports far beyond the counselor’s office.

NEA Today spoke with educators at Lakeside Middle School in Millville, N.J., who have embraced this holistic approach. Here they share their tips for smoothing students’ return to school this fall.

High Anxiety

A’yonna Costin, a rising ninth grader at the school, had a hard time with hybrid learning. “It was challenging for every-one, even our teachers,” she says. “Going back full-time will be a great opportunity for everyone because we will be more focused on schooling and how we were before COVID-19.”

Still, she wonders, “How are we going to maintain social distance with everyone in the school building together? If cases start to rise again, are we going to have to go back to virtual? Will I catch COVID?”

A’yonna also admits that she wasn’t as focused as she should have been during the last school year, and she missed a lot of assignments. She started feeling pressured to the point of thinking about dropping out.

“But I won’t do that,” she says. “I’ve learned to focus on one subject at a time and not let it all pile up on myself.”

Tip #1: Ask what students missed

Students develop part of their identities by participating in the social aspects of school. Band or choir performances, plays, sports, and the ritual of the prom offer connections. What students choose to participate in is part of who they are.

Ask students to talk about what they missed. Is there something that can be done to make up for it? Encourage them to brainstorm ideas for a “post-pandemic prom,” a students-against-educators sporting event, or a back-to-school concert.

‘If trauma is the problem, empathy is the cure’

For help, A’yonna turned to paraprofessional Ashanti Rankin, who works with Lakeside students on behavioral and emotional skills. Rankin has always taken a holistic approach to working with students by meeting them where they are; checking in on their emotions; and helping them manage difficult feelings. Over time, he says, the students begin to trust that you do want to build a relationship, and they feel more comfortable working on solutions to deal with problems.

“These are kids, humans,” he says, adding that the most important thing for humans is connection. “Executive skills and empathy go hand in hand.”

There have always been students at Lakeside who are dealing with trauma, but during the pandemic, the district recognized these stressors in new ways. Schools gave students more leniency for assignments and other classwork if they were struggling with traumas related to COVID-19. And students were encouraged to talk about their trauma so they didn’t have to carry the burden alone.

“The empathy that’s been shown and the grace in allowing the students to bring their trauma—to simply talk about it—has made a huge difference. If trauma is the problem, empathy is the cure,” Rankin says.

This year, Rankin expects that the biggest emotional issue facing students will be grief.

“There’s grief not just for their family members dealing with COVID [and] the traumas of the racial reckoning, but also grief about the expectations of what students wanted to do in their yesterdays,” he says. “They feel like they’ve been robbed of these memories of what should have been, and we need to acknowledge it, let them express it, and show some more grace.”

Tip #2: Engage and acknowledge identity and oppression

Grief, identity, race, and trauma have all been brewing in the same stew. To keep students from reaching a boiling point, New Jersey paraprofessional Ashanti Rankin recommends the framework of Gholdy Muhammad, author of Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy.

“She starts with developing identity. If you don’t know who you are, if you don’t have a strong sense of self, you’ll have troubles in school and in life,” Rankin says. If we start with her framework and look at the whole child, we can make gains in SEL and academics simultaneously.

Muhammad’s Framework:

• Identity Development: Helping youth to make sense of who they are and others

• Literacy Skill Development: Developing proficiencies across the content areas

• Intellectual Development: Gaining knowledge through literacy practices

• Criticality: Developing the ability to read texts (including print and social contexts) to understand power, equity, and anti-oppression

• Joy! Helping youth to see the joy in themselves and others

We need to connect

Jaclyn Eppright, a counseling social worker at Lakeside, says many students have requested to meet with her more often. And those are the students she knows about. She suspects there are more who have yet to ask for help. During virtual learning, some students experienced trauma at home, such as abuse, domestic violence, and the impacts of poverty.

“It will be imperative for schools to take the time to really look at ways to support students,” she says. “That means SEL incorporated within the classrooms, less academic pressure, and more counseling support. I know the foundation of a school is to provide education, but we have to remember that academics take a back seat to safety. When our students feel safe they’re able to learn.”

At a recent conference, she took to heart the words of a speaker who suggested using the term “physical distance” rather than social distance, because, more than ever, we need to stay connected socially.

“I think we need to really consider the social-emotional aspect of this pandemic for all ages,” Eppright says. “For younger students, this way of school is all they know, and for high schoolers, they’ve missed out on major events that support them socially, like sports and prom. We have to recognize and empathize that this is a loss for our students on so many levels, not just academically.”

Tip #3: Relationships, relationships, relationships!

“Relationships are the agent for change, and the most powerful therapy is human love.”

—Dr. Bruce D. Perry, author

Counseling social worker Jaclyn Eppright says this quote drives her work with students.

“My number one tip to any educator is to build a positive relationship with your students,” she says. “Take a few extra minutes to get to know your kids and their interests.”

In Her Words

Shaniqua Williams, counselor at James Wood Middle School, in Winchester, Virginia

There is a huge uptick in mental health concerns. We’ve seen it in online searches: “I’m depressed,” or “How do you tell your mom you’re gay?,” or even, “I want to kill myself.” We try to provide the necessary support in the guidance office, but there are not enough outpatient facilities. One student said the waiting list is three to four months long.

Kids are coming into the guidance office much more often. That helps us build relationships with them, but we’re not supposed to provide long-term care for the serious issues we’re seeing, such as depression or self-harm. We need more community resources to work with our schools.

‘They are not behind’

As a sixth-grade counselor, I worry about my kiddos who didn’t have a chance to build relationships with their teachers in elementary school and now have to adjust to middle school. That’s always a hard transition, but it will be extremely stressful this year.

For some students, the last time they were in a school building was in fourth grade. It’s important that we all work together to make them understand they are not behind—there are just some things they haven’t learned yet.

‘We [must] work through our own trauma first’

We all want to be there for our students, but we can’t do that unless we work through our own trauma first. Like for many other educators, this doesn’t come easily to me, so I try to keep learning. One terrific resource is the book Trauma Stewardship: An Everyday Guide to Caring for Self While Caring for Others by Laura van Dernoot Lipsky and Connie Burk. I read it in a book club at work, and I’d recommend it for all educators.

‘You did do something right today’

I also partipated in one of NEA’s professional learning courses on SEL. I picked up a lot of helpful tips, but one lesson has really stuck with me: No matter how your day starts, choose to finish well. I always tell myself, you did do something right today.

We often go through the day in a blur, but I tell my colleagues to take stock of what they accomplished. Know that the day wasn’t a total wash and someone is looking forward to seeing them tomorrow. End on that positive note.

Like the day a boy walked up to me, gave me a fist bump, and just started talking about his math test. He wanted to share with me. And I was so glad to be able to celebrate with him. That day, I finished well.

I try to remind myself and my colleagues, there will always be a smile in the day, just look for it.

Lysol is HERE to Help Support Schools

- Learn More

Family ties

Rankin has seen grief and anxiety affecting his own children, too. He could tell his stepson Isayah was stressed when he started sleeping more, and stopped talking with his friends or even playing with the family dog.

“When he’s stressed, he’s silent,” Rankin says.

Isayah, who is entering his senior year, says he felt emotionally drained. During the last school year, he wanted to keep up, but there was so much work, and his teachers didn’t always respond to his needs.

“First semester all of my teachers would text me back and have some kind of relationship with me, but second semester, some didn’t really talk to me,” he says. “In some classes, they pushed out so much work because we needed to get to all the topics for the exams, and I didn’t really understand all of it. I’m worried about the upcoming year, because I was barely understanding some of the earlier material.”

It’s likely that Isayah’s teachers were as emotionally drained as he was. Burnout is at an all-time high, and just as we are asking educators to give grace to their students, “we need to give grace to [the educators], too,” Eppright says.

“The profession is challenging enough and now the demands put on us are unbelievable,” she says. “Just like kids, if we don’t feel safe in the environment we work in, we’ll be in fight or flight mode and won’t produce our best work.”

Tip #4: ‘Restorative circles’ support educator mental health

Gina Harris is a culture and competence coach in Oak Park, Ill. Her whole day is focused on addressing the social and emotional needs of students and educators. One of her strategies is to gather members of the school community in a monthly dialogue event called “Coming Together.”

“We invite everyone—administrators, students, parents, family members, teachers, ESPs, and everyone connected to the school—to sit in a circle,” she explains. “We pass around a speaking stick and give everyone an opportunity to share. Parents hear about kids’ and teachers’ experiences; educators hear about the challenges of administrators—and how the [administrators] would like help solving them.”

Harris says these ‘restorative circles’ help build and repair relationships through equal opportunity sharing and listening.

Students need opportunities for connection, too, Harris adds.

“I encourage teachers to set time throughout the day for pausing points, where everyone can stop, breathe, and acknowledge what everyone is feeling,” she says. “You’d be amazed what one minute of breathing can do.”

Join Us

Self-care still works

Many educators say tending to their self-care is like following instructions for airplane oxygen masks. Put on your own mask first before helping others, because if you run out of oxygen, you won’t be able to help anyone.

Likewise, if you’re stressed you won’t be able to ease the stress of your students, says Lakeside social studies teacher Hannah Varner. And this year, there will definitely be a lot of stress.

“There will continue to be uncertainty among our students, especially for those living in poverty. They worry, will we still receive free meals, have access to technology, and be kept safe from COVID? They’ll need extra reassurance and resources to help them cope,” Varner says. “They’ll need a caring adult to explain things to them and be a calming presence; to let them know that change can be OK and show them how to deal with it.”

If one of her students is having a stressful day, Varner tries to sit and talk with the student for a few minutes. Sometimes just being able to process things is enough to help students move past that block and get their focus back, she says.

“Sometimes, the only positive interaction a student has during the day is with a staff member at school,” Varner explains. “Showing that student that you care and know that they can succeed can completely change the way the student reacts to you, others, and even themselves.”

The state legislative battle for school counselors

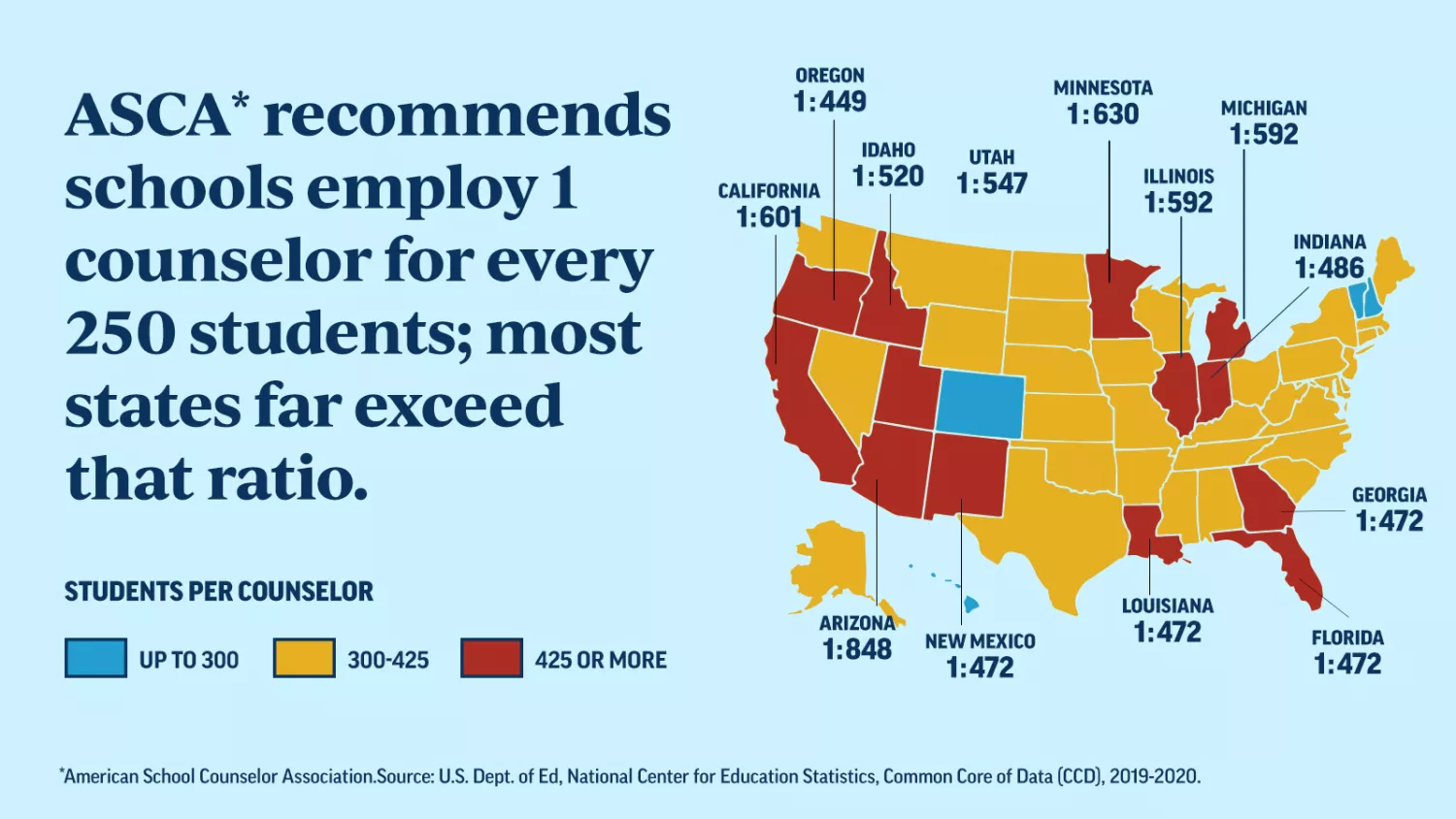

In Tennessee, elementary schools aren’t required to have counselors. The other day, counselor Lauren Baker was talking to a colleague who serves three elementary schools alone, spending a few hours here, a few hours there. It reminded Baker of her early career days in East Tennessee, working with 900 students alone.

Today, Baker shares her 800 elementary students in the suburbs of Memphis with another full-time counselor. That’s a comparatively better ratio, and yet she knows she could provide more intensive mental health support to students and families if she had only 200 or 300 students.

Many Tennessee legislators agree. This spring, a bill that would lower the student-to-school counselor ratio to 1-to-250, which is the American School Counselor Association’s recommended ratio, passed in the state’s House of Representatives but stalled in the Senate.

“This is absolutely, 100 percent the way to go,” says Baker. “Every counselor I’ve talked to, not one of them needs another program. They need more help.”

Can lawmakers help?

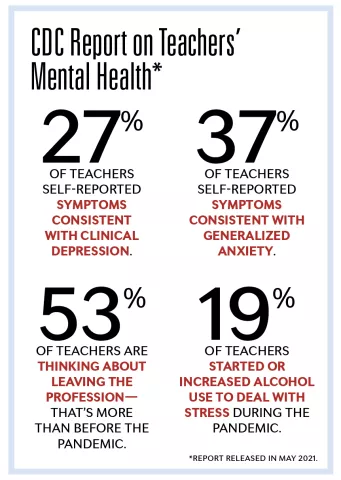

Children’s mental health needs have been growing for decades—and they’ve only gotten worse during the pandemic. Finally, through the advocacy of NEA members and parents, some legislators are getting the message.

In Michigan, for example, psychologist and state Rep. Felicia Brabec sponsored legislation this year to require one counselor for every 450 students. Currently, Michigan’s student-to-counselor

ratio is 671-to-1, the second worst in the nation, behind Arizona.

Last year, it was 760-to-1, but Michigan Middle School Counselor of the Year Betsy Kanagawa notes that the better ratio likely is a side effect of the pandemic, and not necessarily a good thing.

“It’s only lower now because we have so many students in Michigan that we can’t find!” says Kanagawa, who has 440 student assigned to her this year—the highest number in her 10-year counseling career.

State lawmakers are listening, student advocates hope. Last year, in Virginia, state lawmakers mandated a 375-to-1 ratio in elementary schools; 325-to-1 in middle schools; and 300-to-1 in high schools, where counselors also provide career and college readiness services.

In California, lawmakers set aside $75 million in new grant money for preventive services. New mental health bills also have been filed this year in Washington and New Jersey.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” Baker says. Mental health support for children costs money, and only a handful of states spend less per student than Tennessee, she acknowledges.

The need for more investment

While increasing mental health care requires money, not doing anything can cost more in terms of students’ health and well-being. “The level of anxiety I’m seeing … it’s clinical anxiety and depression, and it’s dramatically different,” says Baker, who is in her 16th year as a school counselor. “Even at the elementary level, I’ve had kids being treated in residential facilities. I didn’t see that when I first started.”

Kanagawa also has seen an increase in the number of middle school students she refers for crisis screenings, as well as those who require hospitalization. There is more homelessness, too, she notes. When her school returned to in-person education during the last school year, the students all took mental health screenings, triggering interventions.

“How do counselors with 750 children identify those supports, make those contacts, and make those interventions? It’s an overwhelming task,” she says.

“We’re just not spending our [state] money in a way that shows our support [for these children],” she says. “I hope this passes. The problem is, it probably won’t if they can’t figure out a way to pay for it.”

—Mary Ellen Flannery

Register now for NEA Fall SEL Courses

Get more from