Key Takeaways

- NEA is building and growing a community of activists to help advance racial equity in public education.

- Learn how retired educators are taking their lessons learned to create policies and practices that improve the outcomes for all students.

- How much do you know about racial equity? Test your knowledge.

From yesteryears to now

“I grew up poor,” Salamone says. “My mother couldn’t pick me up. We didn’t own a car.”

For students today, particularly students of color who make up most of the Buffalo Public Schools’ student population, the same all-access pass comes with restrictions.

“Kids have specific routes they must take,” explains Salamone, who taught history for more than 23 years in Buffalo, before retiring, in 2021. “If the driver checks your pass, and it’s not for that bus, the driver won’t let you on.”

Quote byChristine 'Chris' Salamone

Plus, students can only use the bus pass at specific times.

In 2015, Salamone along with other members of the Buffalo Parent Teacher Organization—a districtwide group created by her state union, NYSUT—challenged the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority and forced them to end this practice.

“Most of our parents don’t have cars, and the bus pass allowed students the freedom to do what they had to do,” she says. “A lot of our kids play sports after school. They need to get home afterwards.”

But two years ago, transportation officials reinstated the bus pass restrictions.

“By limiting the students’ mobility, they’re limiting their lives,” she says.

A classic case of systemic racism

How is it systemically racist to limit an all-access student bus pass? Because it’s a policy, embedded as part of an organization’s normal practice, that negatively affects a particular group of people. In this case, it impacts students of color disproportionately. But these systems can be broken down.

“Someone, who is non-racist, will say: ‘Yes, racism is bad. Everybody should have equal rights and equality.’ An anti-racist not only believes in that, but acts to make it a reality.”

—Aaron Dorsey, NEA’s Center for Racial and Social Justice

Racial justice, or racial equity, goes beyond non-racism, says Aaron Dorsey, a national trainer with NEA’s Center for Racial and Social Justice. It’s not only the absence of discrimination and inequities, it’s also the presence of deliberate systems and supports to achieve and sustain racial equity through proactive and preventative measures.

Retired educators like Salamone are working toward these goals.

“If you’re really anti-racist, you’re gonna do whatever you can to change the system,” Salamone says. “We’re fighting with the bus company to remove the restrictions—again.”

What is anti-racism?

What is the difference between non-racism and anti-racism? “Someone who is non-racist will say: ‘Yes, racism is bad. Everybody should have equal rights and equality,’” Dorsey says. “An anti-racist not only believes in that but acts to make it a reality.”

These are activists who rally on the streets for justice; write letters to elected officials to challenge policies that harm historically marginalized people; or support racial justice organizations financially or by volunteering, he explains.

“Most people fall into the non-racist category, but anti-racists are doing the work to unlearn racist ideas and calling out racism when they see it,” Dorsey says.

What it means to do the work

Why Talk About Race?

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00The goal? Advance racial justice in their communities.

“It was a powerful experience,” Ward-Gravely says. “We talked about the history of African Americans, Native Americans, the internment of Japanese Americans, Muslims, and others who have been oppressed in this country.”

She adds: “To hear about these experiences and know common ground existed then, and that people to this day are committed to this work, was inspiring.”

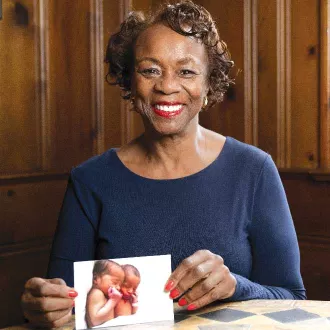

Ward-Gravely would soon draw upon this learning when her twin grandsons, Caiden and Christian, ran up against systemic racism at school.

Caiden and the lunch lady

In August 2022, just a week into the new school year, 9-year-old Caiden was sent to the principal’s office.

“My grandson went through the lunch line, picked up a yogurt and fruit, walked to his table, sat the items down, and then went back in the line to get the rest of his lunch,” explains Ward-Gravely, who received a call from a parent who had witnessed the incident.

When Caiden went to enter his code to pay for lunch, the cafeteria worker accused him of theft. Caiden explained to no avail that the yogurt and fruit were part of his lunch. He was sent to the principal, who also accused Caiden of theft.

Ward-Gravely underscores that the White parent who contacted her is anti-racist, because she saw racism and took action to stop it.

“When she sees an injustice, she addresses it,” says Ward-Gravely. “And we want everybody to be able to do what she does.”

The woman’s actions led Ward-Gravely to immediately set up a meeting with the principal. Unfortunately, the principal repeated the accusations and stated that this was Caiden’s first strike. Next time, he would be suspended.

“This is how systemic racism works,” Ward-Gravely says.

She notes that harsh discipline—such as going from a warning to a suspension over a misunderstanding—are detrimental to students of color, who often face severe punishment over minor infractions. This, in turn, feeds the school-to-prison pipeline.

Quote by—Valenta Ward-Gravely , retired educator, Ohio

Christian and the counselor

Fast forward to early April 2023. Christian was sent to the principal’s office over the use of profanity.

“Yep, this 9-year-old says to the counselor: ‘Leave me the f- - - alone,’” his grandmother recalls. “Whoa, that was a wrong thing to say.”

What was behind the f-word? Grief, frustration, and displeasure.

In December 2022, the twins’ father had died. A month later, a memorial service was held. Toward the end of March, Christian had strep throat and was out of school for three days.

When he returned, the counselor—who was working with Christian as part of a small group of students—knew of his father’s death and that Christian was allowed to call his mother at any time.

But that day, the counselor wouldn’t let Christian make the call unless he explained why it was necessary.

The truth? Christian was angry because another student had taken something off of his desk and thrown it in the trash. But Christian didn’t want to share that with the counselor.

“He wanted to talk to his mother,” Ward-Gravely explains.

The principal wrote a notice of intent to suspend, which included language with criminal implications: “Destroy or damage property on purpose,” “assault,” “make a physical/verbal attack on,” and “causing damage to the property of another.”

Ward-Gravely makes the poignant point that the administrators and staff involved at her grandsons’ school were African American.

“African Americans are not exempt from having a systemic racist perspective, because that’s what we were all brought up in,” she says. “Eliminating it requires education and training and learning and unlearning to remove some of those concepts, thoughts, and perspectives that harm African American people.”

Dismantling systemic racism in real time

In each instance, Ward-Gravely reached out to school staff to talk about the incident. Afterward, individual staff members apologized to the boys.

As for Christian, Ward-Gravely and her daughter filed an appeal.

During the meeting, they talked about systemic racism and the school-to-prison pipeline. They asked about suspension rates based on race and ethnicity.

They also requested that the criminal language in the report be replaced with an accurate description of events—“use of profanity toward a staff member”—which does not carry criminal implications.

The request was granted.

“Not every parent would know to challenge the criminalizing nature of the words used in their child’s suspension,” she adds.

Ward-Gravely credits NEA’s training with giving her the tools to take anti-racist actions on her grandsons’ behalf. Today, many active and retired educators across the country are engaged in similar trainings, so they, too, can stand up for racial justice.

The Language of Anti-Racism

“People often use words interchangeably,” says Aaron Dorsey, of NEA’s Center for Racial and Social Justice. “Did the person mean bigot instead of racist? Grounding ourselves in the terminology … sets the foundation for conversation around race and equity.” These commonly used words related to race can be loaded with meaning:

“Colorblind” is a misguided term describing the act or practice of disregarding racial characteristics or being uninfluenced by racial prejudice. “Color blindness” is often promoted by those who dismiss the importance of race to proclaim the end of racism. The term presents challenges when discussing diversity, which requires being racially aware, and equity, which is focused on fairness for people of all races.

Equity means fairness and justice, and it focuses on outcomes that are most appropriate for a given group, recognizing different challenges, needs, and histories. It does not mean “equality,” or “same treatment,” which do not take differing needs or outcomes into account. Systemic equity involves a comprehensive system and process that creates, supports, and sustains social justice.

Inclusion involves authentic and empowered participation in a group or structure, with a true sense of belonging and full access to opportunities.

“Reverse racism” is a concept based on a misunderstanding of what racism is. Every individual can be prejudiced and biased, but racism is based on power and systematic oppression. Even though some People of Color hold powerful positions, White people overwhelmingly hold the most systemic power. The concept of “reverse racism” ignores structural racism, which permeates all dimensions of our society, routinely advantaging White people and disadvantaging People of Color. It is deeply entrenched and in no danger of being dismantled or “reversed” any time soon.

Systemic analysis is a comprehensive examination of the root causes and mechanisms at play that result in often invisible obstacles for People of Color. It involves looking beyond individual speech, acts, and practices to the larger structures, such as organizations, institutions, traditions, and systems of knowledge.

Test Your Knowledge

Text ANTIRACIST to 48744 to see how much you know about equity terms and phrases—and about the resources needed to promote dialogue around equity and inclusion.

Explore NEA’s racial and social justice trainings at nea.org/Social-Justice-Trainings.

Education News Relevant to You

Get more from