Key Takeaways

- Roughly 36,000 schools have problems with their heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems.

- As in-person learning returns, ventilation in school buildings is one of educators' and parents' most pressing concerns.

- Through federal and state advocacy, as well as labor-management collaboration, educators are committed to improving the health and safety of schools.

Five school buildings in Wisconsin's Racine Unified School District date to the early 1900s, including Bull Early Education Center (BEE Center), where Kari Schaefer is a speech and language pathologist. Schaefer and her colleagues had longstanding concerns about air ventilation in the building. “Air often just didn’t seem like it was moving through the building as it should,” she says.

Educators in Racine spoke up with these concerns when they were told to report to their buildings in January in anticipation of students returning in March. After a year of remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, half of families opted to send their children back for in-person learning.

As staff at the BEE Center prepared for students, district safety inspectors who toured the building reported that ventilation at the school was up to par.

Schaefer and her colleagues weren’t at all convinced. “It never felt right to us. I just knew that something was off,” she recalls.

Schafer is a member of Racine Educators United, which, with the National Education Association (NEA), proposed a joint union/district safety walkthrough. District leaders agreed. Following the safety checklist created by NEA, inspectors returned to the school one morning and entered a first-floor classroom. The inspector took a long stick with a piece of tissue paper attached to the end and held it up to the vents.

“Lo and behold—the tissue didn't move,” Schaefer recalls. “The ventilation was supposed to be running 24/7 and it clearly wasn’t.”

The district quickly corrected the issue, reprograming the timer of the system to ensure a constant flow of air.

Erratic air circulation was just one of many safety and health concerns that Racine educators carefully documented for the district, and which they wanted addressed before they would step back into the buildings.

“I teach very young kids who are harder to corral into keeping social distancing and mask protocols," Schaefer said. "This was a pandemic, so clean, consistent air quality in the building was not something we were going to ignore.”

Sounding the Alarm

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines have been clear: improved ventilation and indoor air quality is a core virus-mitigation strategy needed to reopen schools in-person safely. Schools, according to the guidelines, should increase air filtration and increase the amount of outdoor air that flows through their HVAC systems.

But for too long the nation has neglected its school buildings, especially those in lower income areas where students and their families have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

A June 2020 report by the General Accounting Office (GAO) estimated that 54 percent of public school districts need to update or replace multiple systems in their school buildings, with HVAC topping the list. Forty-one percent of districts need to replace or update these systems in at least half their schools —roughly 36,000 schools across the country.

Educators have been sounding the alarm about “sick” schools for years, if not decades. Long before the emergence of COVID, students and school staff in old buildings have endured mold, leaky ceilings, and frequent colds and flu, as well as increased asthma rates from poor air circulation and lethargy and nausea caused by high CO2 levels.

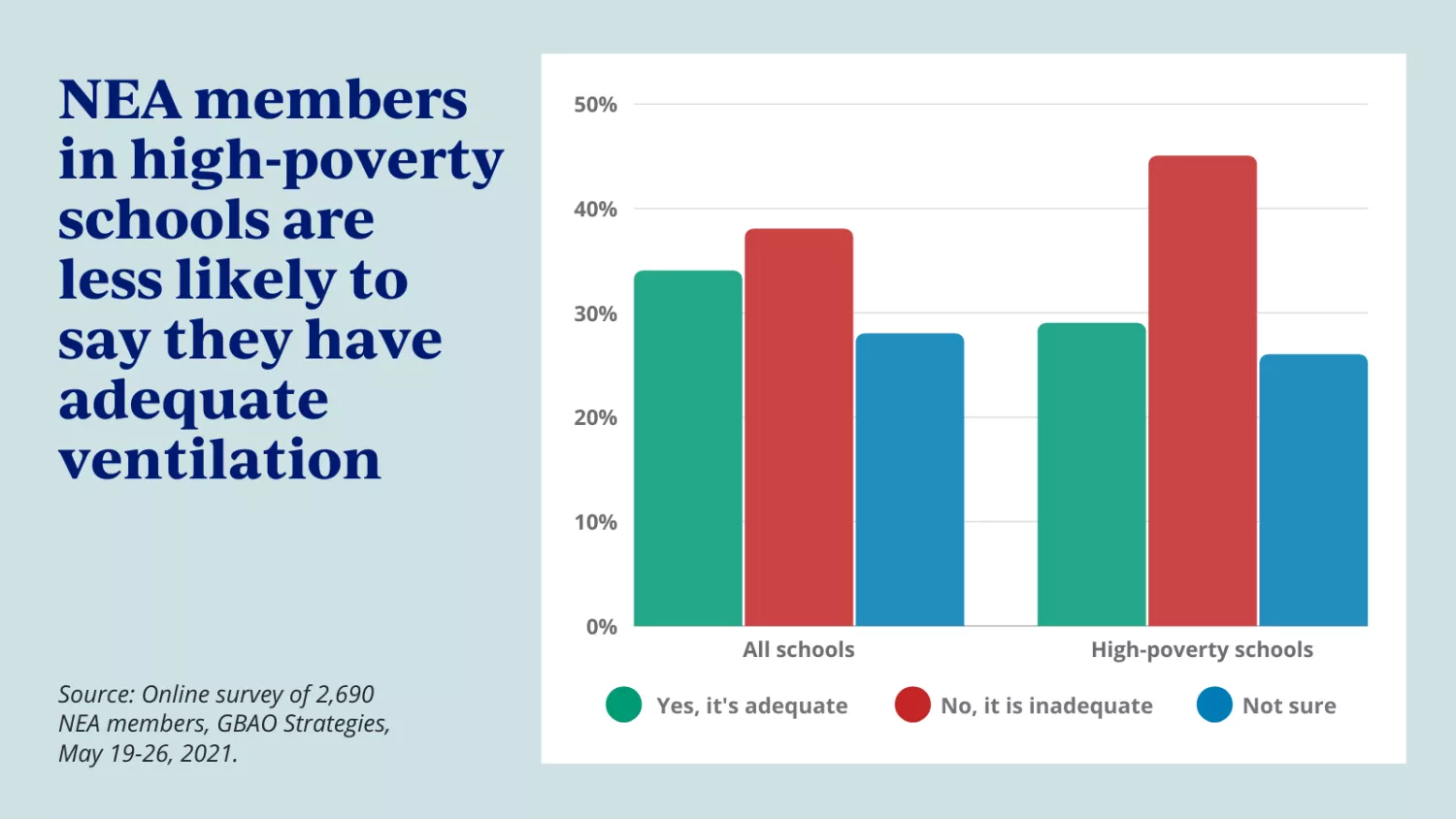

It's not surprise then that, as in-person learning returns, ventilation in school buildings is one of educators' most pressing concerns. According to a recent NEA survey of its members, only about one in three report that adequate ventilation has been implemented in their schools. Members in higher poverty schools are less likely to have adequate ventilation. When directly asked whether they think their school’s ventilation system is providing them enough protection from COVID-19 to feel safe working in-person, 34 percent said yes, 38 percent said no, and 28 percent said they weren't sure.

Parents are also worried about air quality in their children's schools. A June 2021 Rand survey found that, among parents unsure of whether they will send their children back into buildings in the fall, ventilation in classrooms was the top-ranked safety concern

Schools Are Infrastructure

Kimberly Scott-Hayden, the 2021 NEA Education Support Professional of the Year, has toured every school in the East Orange, New Jersey, district where she serves as an inventory control clerk. Newer schools have working air conditioning and proper ventilation, while older schools do not. “There is a building less than two miles away from the Board of Education headquarters, which is over 100 years old," she says.

Lower-income communities with the most dilapidated school buildings are often left with few funding options, disproportionately effecting students of color, students with disabilities, and students in rural counties.

"These are inequities that impact your child," Scott-Hayden said. "Many inner-city communities don’t have the tax revenue to replace and rebuild schools in need so we have to depend on state and federal dollars.”

Many lawmakers are listening, but more—much more—needs to be done. In March, President Biden signed into law the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP), which includes $170 billion for public schools. This allocation, the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), can be used to improve indoor air quality in schools, as well as to modernize these buildings to reduce risk of virus transmission.

The Connecticut Education Association (CEA) has been advocating for ARP funds to modernize schools' air quality systems, including heating and air conditioning and mold remediation. In June, hundreds of schools in the state were forced to close because of defective air conditioning or proper ventilation systems.

Federal funds, said Ray Rossomando, CEA director of policy, research, and government affairs, "can make our schools cleaner, safer, and available year-round."

As vital as ARP has been, a greater investment can be found in the administration’s historic infrastructure proposal, the American Jobs Plan, which includes $100 billion to modernize K-12 public school facilities.

NEA also supports the Reopen and Rebuild America’s Schools Act, which would create a $100 billion grant program and $30 billion tax-credit bond program targeting high-poverty schools whose facilities pose health and safety risks to students and staff.

'It Was Dangerous to Call Everyone Back'

Long before the passage of the American Rescue Plan and the approval of COVID-19 vaccines, educators in virtually every school district faced enormous political pressure to return to in-person learning—even in environments that were demonstrably falling short in critical health and safety protocols.

When educators in Racine were ordered to report back to their school buildings in January 2021, Racine Educators United (REU), which brings together the Racine Education Association and the Racine Educational Assistants Association, determined to use their collective voice to improve the safety conditions at the district’s 26 school buildings.

“The whole narrative that we didn’t want to return and be in the classroom was absolutely ridiculous,” says REU President Angelina Cruz. "We all wanted to go back. But from our perspective, it was dangerous to call everyone back. There were too many unknowns.”

"So we told the district leadership, ‘Let’s work together and figure out a way to make it as safe as possible.'"

Labor-Management Collaboration

Initially, the district's reopening plans were vague and inadequate, so "we had our members document every concern they had about their building," recalls Kari Schaefer, who was one of a team of building safety reps recruited by REU to serve as the eyes on the ground.

REU identified deficits throughout the system—masks that were too large for the youngest students, malfunctioning hot water, inadequate supply of alcohol-based hand sanitizers—that were quickly fixed by the district.

Cruz says that, while REU was assertive in their demands, "we weren't playing gotcha with the district. This was about troubleshooting." In fact, the district was receptive to educators’ concerns, a trademark of the generally collaborative and constructive relationship REU had with the RUSD Chief Operations Officer and her team.

The problems around air quality that REU members identified (at least one in each school building) were on a different scale.

"We're educators, we're not experts on HVAC and air quality," says Cruz. "So we needed guidance and resources."

REU reached out to a NEA team that assists state and local affiliates with health and safety protocols for school reopening. Working with industrial hygienists, the team identified and documented air quality hazards in the school and reviewed ventilation studies of each building supplied by the district. NEA staff and REU leaders met regularly with the district.

"It was very collaborative. We wanted to work as a team and we did. The district was responsive to what we wanted done, " says Cruz.

As problems were identified, the district took steps to address them—even when it came to the installation of new, unproven technologies.

Unproven Technology

Under pressure to improve air quality as schools reopen, districts across the country have purchased costly, air-filtering technologies—bipolar ionization systems—that many experts believe are potentially harmful to students. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, these systems may generate ozone and other harmful bi-products.

Racine Unified was already receiving bids from companies to install this technology in schools until NEA's team flagged the potential harmful consequences for REU. In a subsequent meeting, the district agreed to drop the plan in favor of deploying individual air purification units wherever needed. In addition, the district agreed to install MERV-13 air filters in every school building by the 2021-22 school year.

Once these units have been installed, says Schaefer, educators will be confident that their buildings—as long as other mitigation strategies continue—are safe enough for in-person instruction. "I think we'll be good."

The collaborative structure between labor and management that was already in place in Racine helped move the process along enormously. Conflicts inevitably arose, especially during a time of unprecedented anxiety, and more are likely to emerge in the future. Through members’ forceful and strategic advocacy, however, the district understood the gravity of the moment, Cruz says.

"Our organizing was critical. We came up with a systematic way to bring up our concerns and, with NEA's help, brought real expertise to the table. We all had to step back from our emotions and figure out how to work together and not lock horns like we have in the past. This was about health and safety, and everyone understood that."