Key Takeaways

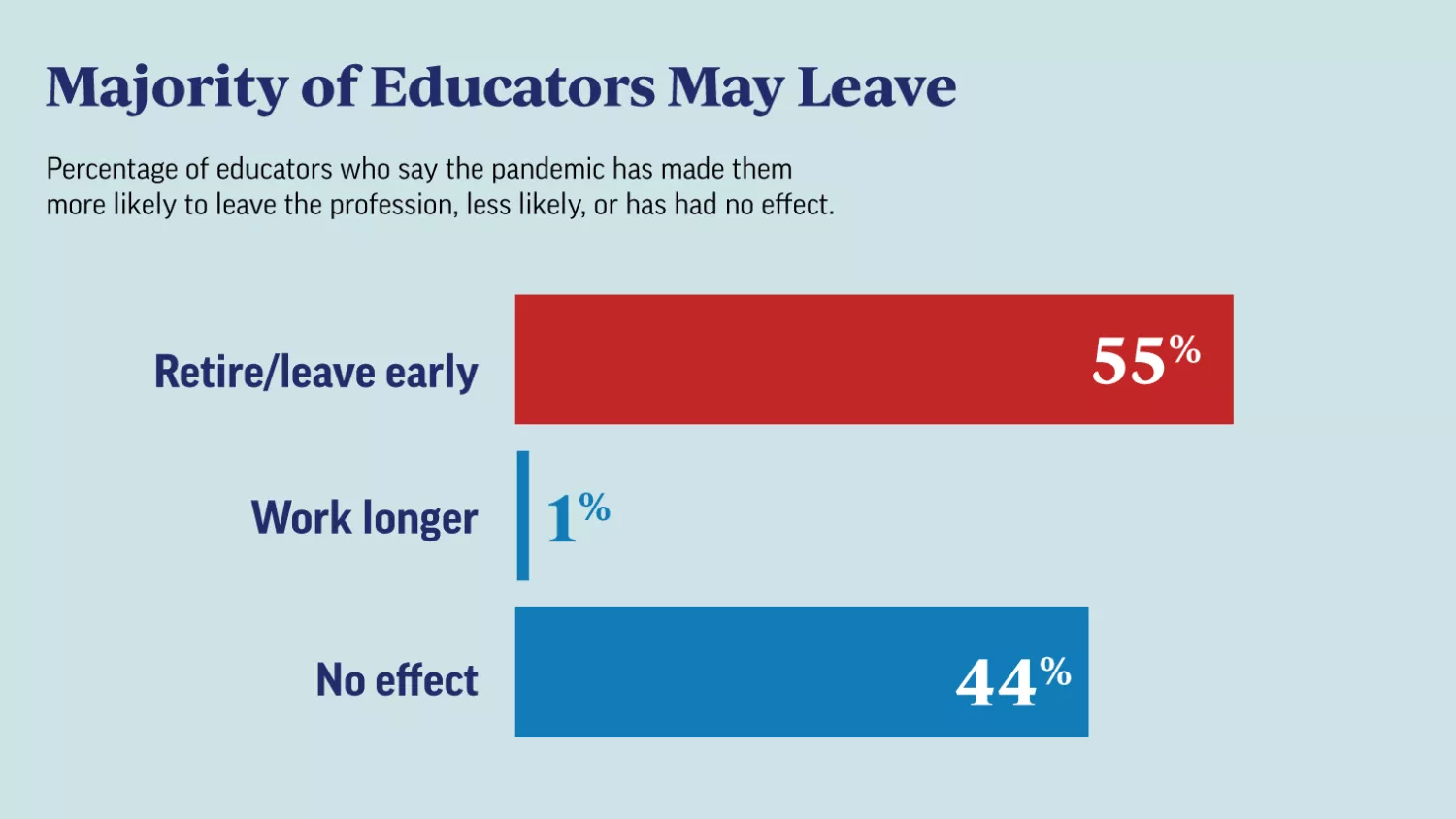

- According to a recent NEA member survey, a staggering 55 percent of educators say they are thinking about leaving the profession earlier than planned.

- While fallout from the pandemic could be the breaking point for educators, mounting dissatisfaction among many in the profession is nothing new.

- To address a crisis that predates the pandemic, says NEA President Becky Pringle, we need solutions that will outlast it.

A Five-Alarm Crisis

Math teacher Sobia Sheikh looked forward to returning to in-person learning in fall 2021. She had missed her students and colleagues and welcomed the chance to rebuild those one-on-one relationships. Of course, she understood that a return to “normal,” whatever that meant, would take time.

But within a few months, she found herself sitting in her car in the school parking lot each morning, summoning the resolve to face another day at work.

Sheikh’s job had become more exhausting. Every morning before she left home, emails were already landing in her inbox with requests to fill in for colleagues. As many as 23 teachers, not including paraeducators, had been out in a single day.

"We're fighting to just make it through the day," says teacher Sobia Sheikh.

“I always want to be there for my colleagues, but I am emotionally and mentally exhausted,” says Sheikh, who teaches at Mariner High School, in Everett, Wash. “For some of us, we're fighting to just make it through the day.”

Sheikh had dreamed of being a teacher since childhood. “I’m scared, because if I left teaching, where would I go?” she wonders.

Across the country, as the spring semester began in New Jersey, another educator contemplated the same question. Social studies teacher Nicholas Ferroni sat down, took a deep breath, and updated his resume for the first time in 19 years. He hadn’t yet decided to leave the profession he loves, but even entertaining a career switch had been unimaginable before this year.

“I’m not sure I can do this much longer,” Ferroni posted on TikTok. “Financially, emotionally, and mentally—it’s breaking me. If things do not change, the system will come crumbling down.”

For years, educators nationwide have been underpaid, undervalued, and underresourced. Now, the pandemic and everything that comes with it—physical and mental health concerns, student learning challenges, and a crushing workload— are pushing an unprecedented number of educators to reconsider their careers.

According to a recent NEA member survey, a staggering 55 percent of educators say they are thinking about leaving the profession earlier than planned.

“This is a five-alarm crisis,” says NEA President Becky Pringle. “If we’re serious about getting every child the support they need to thrive, our elected leaders across the nation need to address this crisis now.”

Extreme Demands

We still don’t know the full magnitude of the pandemic’s impact on public education, but research has long shown that teacher turnover greatly impairs student learning.

In addition, turnover rates are significantly higher in Title I schools and in schools with large populations of students of color. Today, as staffing shortages dovetail with an explosion in students’ academic and social and emotional needs, teacher retention is more urgent than ever.

“COVID has brought all of this into hyperdrive,” says Jennifer Martin, president of the Montgomery County Education Association (MCEA). “It’s a collective trauma we’ve all endured.” During the height of the Omicron wave and resulting staff shortages, Martin recalls, schools and staff in her district were pushed to their breaking points. She warns that lawmakers and school leaders need to do more, because too many educators are on the verge of walking away.

“These educators are not talking about leaving the school they work in,” she says. “They’re talking about leaving the profession.”

Even before the pandemic, the extreme demands imposed on educators were often waved off as unavoidable.

The flawed line of reasoning goes something like this: Educators are driven by dedication to their students rather than money, so they should selflessly absorb the overload and stress of working in underfunded public schools.

It’s time to end that kind of thinking, says Erin Castillo, a special education teacher at John F. Kennedy High School in Fremont, Calif. “We need to change this idea, that teachers should take on everything while being mistreated or disrespected, just because we love being in the classroom or because it’s what’s best for our kids,” she says. “Is it best for our kids to lose great teachers? Because that’s where we are headed,” Castillo adds. Education support professionals (ESPs) are also feeling the impact of shortages all over the country.

“Our support staff is getting pummeled during the school day, and then they have to go to a part-time job just so they can pay the bills,” explains Stacy Tayman, a human resources associate for Calvert County Public Schools, in Maryland, and president of the Calvert Association of Educational Support Staff.

“It’s really hard to be able to manage all of that and then be able to really show up and be your best for students.”

Like other NEA affiliates nationwide, MCEA has been tirelessly advocating for health and safety protocols in schools. The union has secured additional personal days for staff; compensation for educators who are asked to cover classes during planning time; and pay increases for substitutes, who have been desperately needed but difficult to recruit during the pandemic.

A Decade in the Making

In January 2022, there were 389,300 fewer public school educators than there were in February 2020. That’s a sudden and dramatic decline, but educator shortages didn’t start with the pandemic.

NEA closely tracks this issue and, as early as 2017, school districts started having more difficulty in filling job openings— particularly for substitute teachers and in hard-to-staff subjects, such as math, science, special education, and bilingual education.

During the pandemic, however, the shortages have expanded to include nearly all staff positions, including cafeteria workers, bus drivers, and paraeducators. A recent NEA analysis of the education job sector found that staffing declines impacted some educator roles more than others. Employment for teachers and paraeducators, for example, grew from 2007 to 2019, but then fell in the wake of the pandemic.

Similar patterns can be seen for food workers, bus drivers, and librarians. The number of school nurses, counselors, and other mental health workers, on the other hand, increased from fall 2019 to fall 2021.

While fallout from the pandemic could be the breaking point for some educators, mounting dissatisfaction among many in the profession is nothing new. Underlying factors— such as low salaries, equity concerns, lack of support and respect, and challenging working conditions—have been destabilizing the profession at least since 2009, when the Great Recession triggered staggering budget cuts. So what many have called the “Great Resignation,” according to the NEA analysis, has actually been brewing for more than a decade.

Professional Pay Required

Recruiting and retaining educators always begins with professionals salaries. According to the Economic Policy Institute, teachers on average are paid almost 20 percent less than other college graduates, and other school staff without a livable wage, especially in parts of the country with a high cost of living. Up to 25 percent of educators must take on second jobs just to make ends meet.

“At the end of the day, we all love what we do,” Sheikh says. “But we have to provide for our families.”

More than a decade ago, NEA advocated for a base starting teacher salary of at least $40,000. Though NEA has achieved that goal on a national level, more than 5.600 school districts still pay starting teachers less than $40,000.

In the two years before the pandemic, educators and their unions scored some impressive victories under the #RedforEd banner, forcing state legislatures to finally reinvest in education, including higher salaries.

Educators scored salary wins in Indiana, Maryland, and Texas, among others. And, in February 2022, after New Mexico educators marched on the state Capitol, lawmakers agreed to across-the-board pay raises of $10,000. Educators hope the money will help fill the 1,000 teaching vacancies in the state. The following month, Mississippi educators helped secure the passage of a bill that will provide them with the largest pay increase they have ever seen.

While higher pay is the top issue for many educators, other challenges are just as likely to drive them out of the profession.

The fact that the profession has been so undervalued, particularly in a time of crisis, is pushing many educators toward the exits, Ferroni says.

“The pandemic has revealed that the only reason the education system isn’t crumbling down is that teachers and school staff are holding it together,” he says. “We had the same impossible expectations as previous years, but then society and school administrations added on more and more.”

Burnout or Demoralization?

Castillo, now in her ninth year of teaching, is also fed up with the undue pressure that she and her colleagues are facing. What she isn’t suffering from, however, is “burnout”— an overused phrase that she believes amounts to a form of gaslighting.

“What many of us are feeling is beyond burnout,” Castillo explains. “This isn’t on the individual. We’re being set up to fail at this point. When the system does not allow for success, we are being demoralized.”

Educators can and have certainly burned out, says Doris Santoro, professor of education at Bowdoin College, in Maine, but demoralization may be a more accurate term to understand the roots of educator dissatisfaction and exhaustion.

“The burnout narrative comes down to, ‘Sorry, you blew it! You couldn’t hack it, you didn’t preserve yourself,’” she explains. “With burnout, there’s nothing left, no possibility for regeneration. If you are demoralized, however, you are not done.”

Before the recent staff shortages, educators were already dealing with less time for planning and collaboration, highstakes testing, and the silencing of educator voices. These and other trends have eroded what Santoro calls the “moral rewards” of teaching.

She and other researchers have also found that high levels of burnout and demoralization may disproportionately impact educators of color, who tend to leave the profession at higher rates than their White colleagues. Designing and implementing structures and policies that combat these issues, Santoro says, should be every district’s focus.

And while it’s critical to address the current staffing crisis, that success could be short-lived without systemic changes. “Schools should be asking educators: What are the systems that we can put in place so you can do the work that you think matters most? It comes down to support, resources, and autonomy,” Santoro adds.

Changing the Conversation - Again

We need solutions that can outlast the pandemic, Pringle says. “Many politicians, however, have dusted off the old playbook of attacking public schools, and especially educators who have been vocal about health and safety, funding, and the working conditions in schools,” she adds. “Politicians who are set on dividing parents and educators have to start … partnering with us on real solutions.”

With #RedforEd, educators and their unions shifted the conversation, focusing the nation’s attention on the long hours, low pay, and lack of resources that educators have endured for so long.

Educators won another key victory in 2021 with passage of the American Rescue Plan (ARP), the nation’s single largest investment in public schools ever. Under the law, states must consult with educators and their unions when decisions are made about disbursing the funds.

But longer-term investments in education—and strategies to keep educators in the profession—will be needed.

“We need to enhance, not cut, curriculum, [and] rethink evaluations and how we can provide multiple models of support for educators,” Sheikh says. “We also need meaningful professional development, including time to plan, collaborate, and build relationships with our students.”

As an active union member, Sheikh says it comes down to collective bargaining, where it exists, and being unified at the local level. “Our power is in our local association and building relationships with the community,” she explains.

'I Still Have a Voice'

For Sheikh, leaving the profession would mean leaving the students she loves. “I love working with them, and I love hearing from the ones who have graduated and have reached out … to tell me how they are doing,” she says. “Even on my worst days, this is what gives me strength.”

When Castillo thinks back on her first days in the classroom, she remembers her enthusiasm, dedication, and eagerness to do everything that was asked of her at any hour of the day or night. She is still passionate about teaching and dedicated to her students. But she says she has learned to set boundaries and has a clearer understanding about the root causes of educator exhaustion and how to address it.

“I think about my own children. I want their teachers to be treated with respect, so they can walk into the classroom and give my children and my children’s friends a great public education,” she reflects. “What keeps me here is that, as a union member, I still have a voice, and it’s stronger inside the classroom than outside of it. I know what changes need to be made.”

Get more from